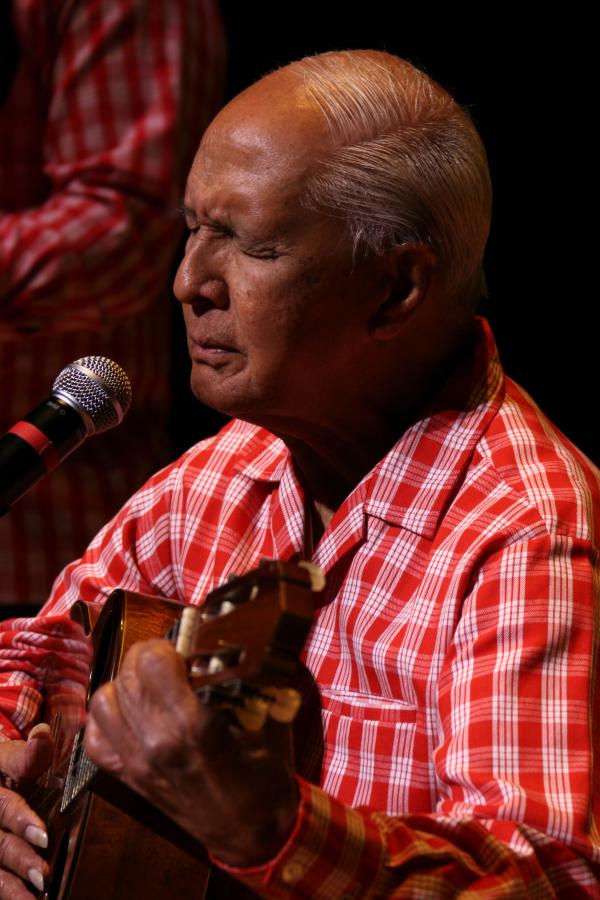

Eddie Kamae

Photo by Michael G. Stewart

Bio

Eddie Kamae was raised in Honolulu and Lahaina, Maui within a family steeped in Hawaiian tradition. His grandmother was a court dancer during the reign of King Kalakaua. Early in his career, he was known for his mastery of the ukulele. In 1949, he toured the U.S. mainland as a member of Ray Kinney's Hawaiian Revue. Kamae became a key figure in the Hawaiian cultural renaissance, co-founding the influential band The Sons of Hawai'i. The band, while garnering a broad audience, became known for the authenticity of its feeling and the unique repertoire, much of which was based on Kamae's deep interest in tradition. In 1974, he helped produce the landmark album Music of Hawai'i part of the National Geographic Music of the World series and with his group produced seven albums of traditional Hawaiian music. During the 1980s, Kamae took up filmmaking to document and preserve authentic Hawaiian cultural continuity. Today he is known as a musical leader and an artist with a voice "both guttural and poetic that carries the spirit of an ancient vocal and chanting tradition into present day Hawaiian music." Among his many honors, he has been designated a Living Treasure of Hawai‘i and has received the Hawai'i Academy of Recording Arts Lifetime Achievement Award. With all of this attention, one nominator says, "Eddie's main focus has always been the school children of Hawai'i …he continues to donate films and study guides and has personally presented to more than 200,000 students in the public schools."

Interview with Mary Eckstein

NEA: First of all, congratulations on your award. Could you tell me how you felt when you heard the news.

MR. KAMAE: I have so many things going on, so many projects, that when I heard about it I said, "Could you call my wife because she can take all the notes on what I need to know." And later on she told me everything. And I said, "Wow, this is very interesting. I like it." Myrna said, "Well I'm going to Washington with you, too." I said, "I like that better."

NEA: What are some of your earliest memories playing the ukulele?

MR. KAMAE: My father would take me what he called jam sessions. In the early years in Hawaii, there were a lot of jam sessions. People would play and the audience members would put money on the stage for the performers. I was around 14 and I followed my father wherever he told me to go to. When they called me on stage, I walked up with my ukulele and started playing, and people threw money on the stage and asked me to do another one. I looked forward to that every week! My father always loved to take me to those, was happy to see me doing things like that. And I began to think, "Oh my God, all these things I've been doing finally pays off."

NEA: How did you learn the music?

MR. KAMAE: My brother, who was a bus driver, found a ukulele on a bus and brought it home. He played it at night and whenever he went to work, I would play it. We weren't supposed to touch anybody else's property in our family, so I didn't ask him, I just waited until he'd go to work, then went and got the ukulele. I'd sit next to the radio and play along with whatever music came on, just to get the feel of the music. That's how I got it. I'd just strum my ukulele and follow along with whatever the rhythm section was. I loved the Spanish music and I loved all the songs. I loved Italian songs. I loved all kinds of music.

NEA: It has been said that the musical group "Sons of Hawaii" helped usher in the Hawaiian Renaissance, a period of renewed pride. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

MR. KAMAE: When I got older, my father said, "Son, you should play and sing Hawaiian music, sing Hawaiian songs." My father came from a valley on the big island, the Waipi'o valley. I didn't know what to say to him, and I couldn't refuse him, but I told him I preferred playing other music. So I didn't focus on it.

But later, after he'd helped me out during a problem period in my life, I thought about what he had said. So I started going to the Queen's Surf and listen to the Hawaiian music and songs. I enjoyed it. And I went to other places where I'd hear musicians play Hawaiian music. I was listening to a lot of Hawaiian music then.

I had been teaching ukulele out at Waikiki and one day, driving from the countryside to town, I stopped by to say hello to some friends, two sisters. They invited me in -- when I walked in, they said, "Guess who's here?" It was [Hawaiian slack-key guitar master] Gabby Pahinui. He was sick and they were taking care of him. Gabby asked if had a ukulele. I said, "Yes, but I'm going to Waikiki to teach." He said, "Get it." I had two ukuleles, so I brought them to him. He took one and started playing. He started singing and strumming and it was a sound that I'd never heard before. It was so sweet and had a rhythm that I loved. So I stayed there. I played with him for four weeks. I told him, "I love this work."

From there, he and I kept playing and then formed a group. I stayed with him day and night and just played music. He then told me to go see a Hawaiian man not too far away and ask him for a certain song. When I went to see the man, the man gave me this piece of paper with the lyrics of the song. And I took it back to Gabby. He started playing. And then the bass player came along, just by accident, to say hello. He went home and he got his bass. As we were playing, he suggested that we needed to get another instrument that would really fill the group up. So we went and got a steel guitar player.

One night the steel player took me to "The Sand Box" restaurant for a drink. We sat down with the bartender and told him we'd been rehearsing and playing music all this time and were ready to go. So he said, "I'm glad you're here because the owner, the manager, is thinking about getting a musical group, because the dance group that's been here is leaving to go to Queen's Surf in Waikiki. If you're interested, talk to him." The manager said, "You are right. You have four musicians?" I said, "With me, it would be four." He said, "Okay, you'll start on Thursdays." I said, "No." He said, "All right, I'll make it Friday, Saturday and Sunday." I said, "Well, whatever days you want." And so I drew up a contract with the musician's union and we started playing Hawaiian music.

NEA: At this point, you were just playing the ukelele. When did you start singing?

MR. KAMAE: Right. I wasn't singing at that time. I was so nervous because it was something new to me. I just wanted play my instrument. At times, I would play the solo to the songs that I loved, but I didn't sing. Then one night after playing, a National Guard pilot in the audience called me over and said, "I take it you're not good in Hawaiian things." I said, "I love what I hear. I love playing with the boys. But I'm not familiar with the language and things like that." He said, "Meet me tomorrow. I'll introduce you to someone who is very dear to my mother." And he introduced me to my first teacher, Mary Kawena Pakui, who recorded the Hawaiian dictionary and many other books. She told me she would teach me.

The following day, the fellow called me and said, "Come on down to my house. I want you to meet someone else," and introduced me to my second teacher, Pilahi Paki. She asked me, "What have you been doing?" I said, "Well, I find this music so interesting that I went to see a friend, and I was guided to the Bishop Museum, and that's where I found Queen Liliuokalani's music and manuscript, wrapped up in a package tied with a string. And when I found that, I said, ‘By golly, here is the music of old.' And I started playing those songs and then I took it to our rehearsal and that was it. And I told Gabby, ‘This song is really beautiful. You should do it.' But he said, ‘If you think it's beautiful, you sing it.' And this is how he got me to sing Hawaiian music."

I was so nervous when I first started singing, my voice would wobble. But my teachers have guided me along the way. One would say, "Now this is the way you would phrase it. From then on, I got the message of what was so important to my father and me. I was on my way, playing Hawaiian music.

NEA: Your first documentary film was about the legendary performer and composer Sam Li'a. How did you get to know him?

MR. KAMAE: My teacher asked me to come along with her on a trip to the south point area of the big island where she was raised. When we got there, I said, "I heard about a songwriter, a beautiful songwriter of Hawaii Pia Valley. Do you know who he is?" And she told me, "Li'a, Sam Li'a." I said, "I'd like to meet him because I want know more about Hawaiian music." She made arrangements for me. All she told me was, "You go here. There's a store right across his house. There's another building next to it. It's a social hall. That's where he lives, right across from the store. You can't miss him." The following week, I went there and he was waiting for me, sitting on his chair. I didn't know how he knew I was coming. When I walked in, he told me to sit down. I told him, "My interest is to this music now." He was in his 90's at the time. He told me about songs he had written and picked up a pad and started writing down the lyrics while he talked. And he would tell me stories about his life. He would say things like, "In the old days, I didn't have much money, so when people come and see me and talk with me, I would write them a song as my gift to them." He did that with a lot of people. He had a heart, a soft heart, and that's what took me. He'd just write things down for me. He'd say things like, "This is when I met my wife and I wrote this song." And he wrote down all this material for me, tore it off and gave it to me and told me the stories around it.

When I came back and saw my other teacher, I told her what happened. When she looked at the material, she said, "You are very fortunate, Eddie, because Sam Li'a is the last of the true Hawaiian poets."

He always encouraged me to come back. Once I brought my wife with me with the jeep. He wanted to take me down and show me the valley where he was born and raised, so we drove down there. We went everywhere. He described the whole thing and wrote it down. And he told me at the end, "You know there is a beautiful woman that lives in the valley, and all the men folk would all go up there and try to find her." I said, "Try to find her?" He said, "Yes, because even my father would do that, and my father wrote a song about her. She was waiting for the right man to come along." He went on like that and I said, "What else?" He just mentioned areas and the place of waterfalls, and he said, "Now here, you write the music." That's when I wrote "Hawaii Pia Valley Song" with him.

When he passed on, I wanted to tell people a story about this kind and gentle man, a man who loved God and who loved people. That's how I got into filmmaking. I just went to the valley with a film group. I didn't know anything about the business, but I wanted to do it anyway because I wanted to tell his story. It was important to me and, I think, to all.

NEA: Do you feel that traditional Hawaiian is in danger of being lost? What efforts are you taking to ensure that that doesn't happen?

MR. KAMAE: The music came a long way with the Sons of Hawaii. Now I'm working with another group. I'm trying to gather musicians so they can feel these feelings of the music of old. That's what I'm trying to share with them. I'm recording some songs right now, songs of old that have never been recorded. I've finished 29 songs. I'm doing it now because I want the musicians to feel and understand what it was like in the old days, how the music was written, and how it was passed along. You know how the young ones have a tendency to follow each other. They hate Hawaiian music, so they want to change it. It's only natural in today's world. But I'm trying to tell the boys that if you can have the steel guitar and the sweet sound of slack-key music, this music will live. I say to the young ones, "You say you're Hawaiian but you're doing something else. You must feel your grandfather and grandmother's days and the music of that time and share that with others." That's what I try to tell the children in schools. Ask your grandparents what life was like, what the sound of music was. What was the lifestyle like? That's what I want them to do to keep this music alive.

NEA: What has been your greatest source of either pride or happiness in the work that you've been doing?

MR. KAMAE: I love playing music for the people. I'm going to be 80 and I still do that. I go to places and sit in with the musicians and play the songs that I love. And the people love the songs and they all come up to me and thank me. I just love these songs. If it touches the soul at all, then I'm happy.