Hustle

OVERVIEW

NEA Literature Fellow David Tomas Martinez is “one of American poetry’s authentic new voices” (San Francisco Chronicle) and “clearly… in possession of a story that needs to be told” (HTML Giant). In Hustle, his debut collection, Martinez reflects on his often violent and chaotic Southeast San Diego youth, including his time as a member of a gang. “Raw and real, full of indelible imagery and lethal language” (My San Antonio), Martinez’s poems “feel simultaneously intimate and spectacular as the voice strikes registers of vulnerability and bravado” (Publishers Weekly). “A necessary addition to Chicano, Latino, and American poetry” (Booklist), “these poems look to the past with resigned brilliance, finding in recollection not just self-knowledge, but a larger truth about the inescapable power of memory and experience to shape us,” writes award-winning poet Kevin Prufer. Author of a second collection titled Post Traumatic Hood Disorder, Martinez “breathes fresh air into American poetry,” writes award-winning poet Ilya Kaminsky. In Hustle, “you will see right away a tone that is restless, metaphors that thrill you, and music that’s so contagious it just won’t let you be.”

“This is mine. / Where is the window to break / in your life?” – from the poem “Calaveras” in Hustle

INTRODUCTION

“Often, the most ordinary fears obscure the most / obvious truths.” – from “Motion and Rest” in Hustle

David Tomas Martinez’s poems in Hustle unflinchingly examine the experiences of his youth—his activity in a gang, the complicated dynamics of his family life, his time in a shipyard and in the navy, and eventually, his discovery of poetry. From the littered freeways, canyons, and backyards of his San Diego childhood to the tree-canopied, uprooted concrete streets of Houston—where he later moves—Hustle shows us a young Martinez negotiating life at the brink of manhood, and later looking back. “Part of my goal in writing this book, which was based chiefly on my experiences, was to allow some of the people I grew up with, many who have been silenced by societal and internal forces, to have a voice” he told 32 Poems.

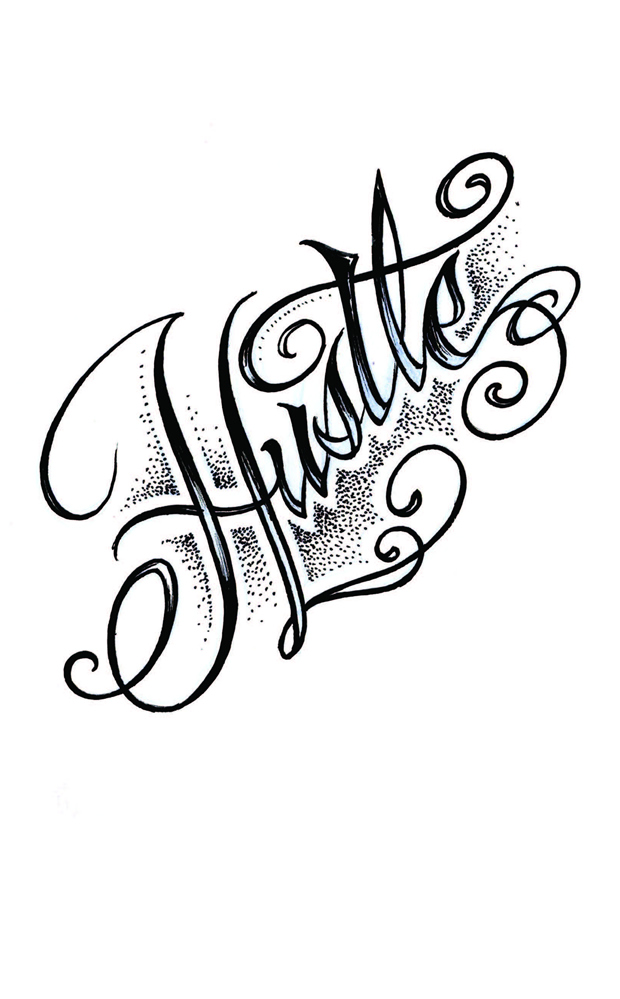

Martinez wanted Hustle to be unconventional and a reflection of his personality. He recruited his long-time tattoo artist, Bryan Romero, to do the book’s cover design, and clues us in at the outset that the viewpoint of these poems will be different from, say, the traditional Romantic-era poems he first studied as a poet. When the speaker of the book’s prologue poem, “On Palomar Mountain,” finds himself in nature, he isn’t struck by its beauty or purity, but instead feels a deep sense of disconnection. “I really don’t know what an oak looks like,” Martinez told My San Antonio, “but I can name All Star-worthy point guards. I could tell you who got shot at the corner of Euclid and Martin Luther King in the summer of 1994 by who and why.”

In the poems that follow, Martinez’s vividly rendered memories become the springboards for reflections on themes such as power, masculinity, identity, violence, and love. “By focusing on craft and by staying close to the language,” he told PEN America, “my words lead me to psychological and emotional truth in ways that just thinking or talking about an experience can’t. There is a certain amount of discovery in the process and I find that in staying close to the language, I’m able to surprise myself.”

“Calaveras” (Spanish for “skulls”), the sweeping 11-part poem that makes up the first section of the book, opens with the speaker attempting to steal a car so he can get hold of a pistol. Chased by police across a freeway, he escapes into a field of cactus and ends up spending his night in a hot bath: “…four hours of needles / shooting from the skin / and holding the faucet like a gun” (p. 7). It is a story that begins with audacity and ends in vulnerability—an arc that echoes throughout the collection. Also reverberating through the book is the question of what it means to be a “man,” with speakers of the poems finding themselves in difficult situations and struggling “with the necessity to be strong because of environment or societal and community expectations,” Martinez told Eckleburg. “I don’t know what being a man is. I do know that we live in a patriarchal society that gives men mixed signals to not show weakness but love your family,” Martinez said in an interview with My San Antonio. “How are you supposed to have feelings if you can’t show vulnerability? How are you supposed to love if you don’t know how to feel?” In poems like “The Only Mexican” (p. 39),“Innominatus” (p. 41), and “The Mechanics of Men” (p. 90) Martinez explores these dynamics in multiple generations of his own family.

Martinez is also interested, more generally, in how we shape our identities and how our identities shape us. For his own part, he says his “relationship with identity can be listed as ‘complicated’” (PEN America). “I’m half Mexican, half white, and I grew up in a predominantly black (it was called Lil Afrika) neighborhood” (Eckleburg). In poems like “To the Young,” he considers how identity is something we project: “To the young / black male / dressed / like a punk rock / hipster club kid / with teddy bears / tied to his sneakers / you too are split / down the middle” (p. 27).

Violence is an undercurrent in many of the poems in the collection, with Martinez trying to make sense of how he responded to and coped with the violence of his youth. In the haunting “Forgetting Willie James Jones” (p. 65), he looks back on the summer of 1994 when a sequence of murders took place, each in retaliation for the one that came before. “I was still angry that [my friend Maurice’s death] had been completely ignored by the San Diego news media, and that Willie [who was valedictorian] was being memorialized… At 17, I didn’t possess the language to understand that my resentment was not with Willie but the lack of empathy for my friend” (Eckleburg). “Motion and Rest” is another poem in which Martinez considers violence—both in nature and an urban environment—and how “commensurately tenuous life is” (p. 47).

Published by independent press Sarabande Books in 2014, Hustle won the New England Book Festival’s prize in poetry, the Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award, and received an honorable mention in the Antonio Cisneros Del Moral prize. It took Martinez almost five years to write. “I loved it after just one read-through,” said Sarah Gorham, editor in chief at Sarabande Books. “Martinez’s history is one of violence, machismo, dangerous sex, father hate, mother love, beat-up cars, drive-by shootings. And yet he has emerged with a poetry keen with emotional intelligence, wild with energy and grief, transcendent even while it rolls in the dust spotted with broken glass” (Poets and Writers).

“You know in any good piece of art when [the writer’s] truth is poking through,” says Martinez. “I know those moments when I write. I think, ‘This is true, this hurts...’ I indict myself in so many poems. I think that to a certain extent, you have to be unafraid to make a fool of yourself” (NBC Latino).

-

Why do you think Martinez chose to title his collection Hustle? What are different meanings you can think of for the word? How do these different meanings shed light on your reading of the book?

-

Martinez has said that every poem in the collection has autobiographical elements. Does knowing that the poems are about Martinez’s own life influence how you read the book? If so, how?

-

The poem “On Palomar Mountain” (p. 1) serves as the book’s prologue. Why do you think Martinez chose to place this poem ahead of the others in the collection? What imagery and themes are introduced here that set the stage for what follows in the book?

-

“Memory is a fist to the eye,” Martinez writes in the poem “Calaveras” (p. 8). Why do you think the speaker of the poem instructs himself—and the reader— to “Remember all that you see” given this painful description of memory? How might you describe other memories of his throughout the collection? Does his description resonate with any of your own memories?

-

Later in “Calaveras,” the speaker says “As a boy I died / into silent manhood” (p. 19). What do you think he means? How would you describe the “manhood” into which the speaker is entering? Can you find examples of this in the book? How would you describe your own experiences transitioning from childhood to adulthood?

-

Describing Chicano Park in San Diego, the speaker states “Not even bags of chips, cheetahs with wind, / avoid being tackled, gouged, and ripped apart” (p. 37). What are some of the other specific details the speaker includes in his description of this landscape? What can we learn about the speaker from what he observes and how he chooses to describe it in this and other poems?

-

Try reading the poem “The Cost of it All” (p. 56) out loud. Does speaking and hearing the words add to your experience or understanding of the poem? If so, in what ways? How about for other poems in the collection? What are some elements of Martinez’s writing—for example, rhythm, repetition, word choice—that stand out to you?

-

Looking at poems like “The Only Mexican” (p. 39), “Innominatus” (p. 41) and “The Mechanics of Men” (p. 90), how would you describe the speaker’s relationship with his father and grandfather? How do these and other relationships in the book inform his perceptions of masculinity and gender? Did you recognize any of your own family dynamics in Martinez’s descriptions?

-

What are some of the comparisons the speaker makes, and dichotomies he explores, in “Motion and Rest” (p. 47)? Why do you think Martinez chose to write this piece as a “prose poem”—using paragraphs—unlike the other poems in the collection? In what ways did the structure of the poem influence your response to it?

-

“Deus ex machina” is a term that Martinez uses in “Motion and Rest” (p. 50). It refers to a plot device in which a situation is resolved—or individuals are saved—in a sudden or miraculous way. Why do you think Martinez is interested in this idea? Where in the book do situations or fates seem inescapable?

-

In “Forgetting Willie James Jones,” Martinez looks back on the summer of 1994, when “death walked alongside us all” (p. 66) and a series of gang-related shootings took the life of his friend, Maurice, and his acquaintance, Willie. What are some ways in which the poem describes morality, power, and/or the effects of violence? Why do you think Martinez chooses to end the poem with the line “How strong I felt in ’94, when the most chivalrous // thing I could do was block a door, / stop a rape”? Do you think the notion of “strength” changes between the beginning and the end of the poem?

-

Hustle’s cover features tattoo script in black ink against a white background. What were the first impressions you had of the book based on its cover design? Now that you’ve read the collection, can you think of ways in which the cover image relates metaphorically to the subject matter of the book? Comparing the cover of Hustle to the cover of other books you’ve read or seen, what are some of the other design choices you notice about Hustle?

-

Why do you think Martinez chose to tell his story—and reflect on his past—through poetry? If you’ve encountered similar themes or subject matter in other forms—for example, in books of fiction or in film—how do those experiences compare to your experience of reading Hustle?

-

Were any of the experiences or situations portrayed in Hustle familiar to you before you read the book? If so, did you find that the poems gave voice to things you’ve been thinking about or feeling? If the subject matter was not familiar to you, are there things you see differently now that you’ve read this book?

Several questions on this list have been adapted from the Sarabande Books Reader’s Guide for Hustle.

The Miami Police Athletic League Celebrates Literature With Their First NEA Big Read

“We at Miami PAL were trying to introduce new ways of engaging the community and getting them interested in books,” said Andra Barnes, director of Miami PAL on why the organization was attracted to the NEA Big Read. He noted that for many young people, having mandatory school reading can make reading as a whole seem like a chore, to the point that they’re turned off from it altogether. “Miami PAL wants to bring that joy of reading back.” Read more about Miami Police Athletic League’s NEA Big Read project on the Art Works Blog.