Pretty Monsters

Overview

This title will no longer be available for programming after the 2020-21 grant year.

Neil Gaiman says Kelly Link, a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellow, should be declared a "national treasure." Holly Black, author of The Spiderwick Chronicles, calls Link "a flat-out genius." "In a place few writers go," writes TIME, "a netherworld between literature and fantasy, Alice Munro and J. K. Rowling, Link finds truths that most authors wouldn't dare touch." Salon describes her as "an alchemical mixture of Borges, Raymond Chandler, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer." Selected as Amazon's Best Teen Book of 2008, Pretty Monsters is Link's critically acclaimed anthology for both adult and YA audiences. Writes Booklist (starred review): "Her conception of fantasy is so unique that when she uses words like ghost or magic, they mean something very different than they do anywhere else. Perhaps most surprisingly ... is Link's dedicated deadpan delivery that drives home how funny she can be." These stories, writes School Library Journal, make "the weird wonderful and the grotesque absolutely gorgeous."

"Whether or not this story has a happy ending depends, of course, on who is reading it. Whether you are a wolf or a girl." —from Pretty Monsters

Introduction

"Her stories are about more than strangeness, more than the fantastic—they're about inclusion, diversity, and acceptance of alternate world views." — Lit Hub

Though all but one of the ten magical and macabre stories in Kelly Link's collection Pretty Monsters were written for young adults, several of them first appeared in publications for adults, garnering Link a cross-generational fan base. The heroes of the stories are mostly teenagers in familiar settings grappling with angst and alienation, awkwardness and awakening desires. That they are also grappling with unexpected monsters, ghosts, wizards, gods, aliens, dueling librarians, pirate-magicians, shapeshifters, possibly carnivorous sofas, and undead babysitters should give readers a hint to keep their expectations in check. Pretty Monsters is part-haunted house, part-fun house, part-safe house, and part-something that doesn't resemble a house at all.

"I like writing from the point of view of children, or young adults," Link told One Story. "They're in this weird transitional space, between worlds. Their actions have real consequences, but that doesn't mean that they're taken seriously.... They want things with a kind of great and terrible intensity that makes them great characters to write about.... When I write about adults, I'm most interested in writing about adults who have retained some of these qualities."

"Magic for Beginners," a Nebula award-winning, metafictional story that's also the title of Link's second book, is about a 15-year-old boy named Jeremy and his friends who are devoted to a surreal, science fiction television show called "The Library" that they watch together and discuss and get lost in while Jeremy copes with his parents' possible separation. It's based on Link's experience watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer during a seven-year period when she moved homes several times. "The one thing [that] all of the places I lived [in] had in common, besides too many books, was a room with a television where we got together with various friends to watch new episodes and then dissect, praise, complain, rewrite and rewatch. It was an enormously social experience, and it's not one I've had since Buffy ended. I wanted to write something that would capture the way it feels to be a fan and a member of a fandom" (One Story).

The Hugo award-winning story "The Faery Handbag" draws inspiration from myths and folklore. A girl is tasked by her grandmother to be the guardian of a black, hairy, 200-year-old family heirloom purse that's home to a whole village. Open it one way and it's just a purse; open it another and it's either the village itself—which, if you go into the bag to see it, you might not return for 100 years—or the dark, threatening land that smells like blood where the guardian dog of the purse lives. The girl makes the mistake of sharing the story of the bag with her boyfriend who gets too curious. Said Link: "I've always loved stories where the insides of something were bigger than the outside" (One Story).

Link's dry humor and witty dialogue are on full display in stories like "The Wrong Grave" about a boy who digs up the grave of his girlfriend to retrieve a poem he wrote and mistakenly buried in her coffin. In "Monster," boys at a camp are bragging about going out in the woods and seeing a monster until one rainy night the members of "Bungalow 6" actually do. It has red eyes and smells of rotting fish and kerosene. James, one of the boys who had just been teased by the other boys in his group right before the monster devoured them (and not him because he was wearing a dress), asks the monster who he is. The monster belches and jokes that he's Angelina Jolie.

Adding to the richness of the collection are illustrations at the start of every story by award-winning, Australian illustrator Shaun Tan. The drawing for "Monster," for example, is a large, pointy-toed footprint next to an open flip phone showing on its screen a mouth full of teeth. Below, a snail glides along like a nonchalant passerby. "You can take her casually enchanted tales literally, or you can read them as allegory; the effect is equally unnerving" (The Believer).

- The narrator of “The Wrong Grave” says things like “a boy I once knew,” and “from my experience,” and “You're not interested in my views on poetry. I know you better than that, even if you don't know me.” And yet, he/she remains anonymous. Whom do you think the narrator could be? How might the story be different if Miles was telling it? Why do you think Link chose to tell the story this way?

- As the narrator tells us in “The Wrong Grave,” the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti buried some of his unpublished poetry with his dead wife, Elizabeth Siddal. Later, he dug up her grave so that he could get the poems (his only copies) back. Is there anything that you can imagine digging up a grave to retrieve? What lasts longer, poetry or grief?

- Though both teach magic, the school in “The Wizards of Perfil” has a curriculum that's a little more alternative than Hogwarts in the Harry Potter series. Can you imagine a world in which there are lots of magic schools, all with different philosophies of teaching? A Waldorf magic school versus a Montessori-style magic school? Would you want to go to one of these, or send your children to one of these schools? Do you think there should be magic taught in public schools? Why, in fiction, is magic so often something that only some children are good at?

- “Magic for Beginners” was written in 2002. The idea for the story grew, in part, out of Link's desire to write about a television show (and its fandom) which was acted, produced, written, and distributed in ways that no actual television show of the time was. How has television and the experience of watching it and being a part of a fandom changed since 2002?

- The characters in “The Faery Handbag” like to frequent thrift stores. They have a theory that “things had life cycles, the way that people do.” Do you ever wonder what stories surround your previously-owned possessions? The faery handbag, in fact, is a family heirloom over 200 years old. Do you have any mysterious family heirlooms? Does your family tell stories of your ancestors that don't quite seem to add up?

- “The Specialist's Hat” is one of the first stories that Link ever published. It was her first attempt at a traditional ghost story in the style of classic ghost story writers like M. R. James and E. F. Benson. It also draws on true stories about ghosts and childhood that her own family and friends told her. What's the scariest true story/ghost story that you know?

- “Monster” fits into a tradition of scary stories about terrible things that happen during camping trips. Much like monster stories and ghost stories, stories about other people's disastrous camping trips (or road trips or travel in general) can be just as enticing—or more—than stories about good camping trips or fabulous vacations where everything went right. What's the worst camping trip or vacation you ever went on? And what do you remember better: the best trip you ever took, or the worst?

- There is an alien invasion at the end of “The Surfer.” There's also a pandemic. In post-apocalyptic stories, these are two of the most common ways in which the world ends. But does the end of the story feel like an apocalypse? Dorn's father loves science fiction. He hopes that the aliens are there to save mankind. Does the ending feel hopeful to you? If you wrote your own alien invasion story, how do you imagine things would go?

- We only get to see a little of the world that Zilla and Ozma live in in “The Constable of Abal.” What can you picture of it? How is it different from our world? How is it similar to other fantasy settings? Ozma shares a name with Princess Ozma, a character in all but the first of Frank L. Baum's Wizard of Oz books. If you've read those books, can you guess why Link chose that name?

- There are at least two overlapping stories in Pretty Monsters: Clementine's story, and Parci and Czigany's story. Does one of them seem more “real” to you, and one more “story like?” If so, why?

- What's scary about being an adolescent? Why would someone want to be a monster?

- There are no overtly fantastical events in “The Cinderella Game,” but there are references to a handful of well-known fairytales, starting with the title of the story. Which ones can you pick out? Is this story itself a fairytale?

- What kind of relationships do the teenage characters in this collection of stories have with their parents? Do the relationships feel realistic? How is the portrayal of these relationships affected by fantastic settings, or the intrusion of monsters or ghosts?

- Link has said that a young adult story is a story about someone experiencing something for the first time: falling in love, betraying a friend or being betrayed, experiencing profound loss or finding a community of people with the same interests, discovering an ability or a talent, coming of age. You can list any number of adult novels or stories that work as cross-over narratives because they fit this theme. Do these stories work differently for adult readers than for young adult readers? Is there any kind of meaningful line between young adult literature and adult literature?

- Can you imagine the characters in these stories as adults? Would they be very different? Do you think that people stay the same as they grow up, or do they become almost entirely different people?

- Link has been commended by critics for, among other things, her humor. Did you find some of these stories—or parts of the stories—funny? Why? How would you describe her particular type of humor?

- Every story in the collection begins with a drawing by the distinguished Australian author and illustrator Shaun Tan, who chose a line from each story to inspire his drawings. Did these drawings affect how you approached the stories? What lines or phrases from each story resonated with you?

- If you could ask the author one question about these stories, or about writing them, what would you ask her?

Bringing Stories to Life in San Diego, CA

Write Out Loud was founded on a simple notion: to read stories aloud for live audiences. This is how it began many of its NEA Big Read events—book discussions included—with accomplished actors reading aloud excerpts from the stories in Kelly Link’s Pretty Monsters. And while there was an emphasis on performative art—the organization was founded by theater artists—Write Out Loud incorporated an array of art forms into its programming.

|

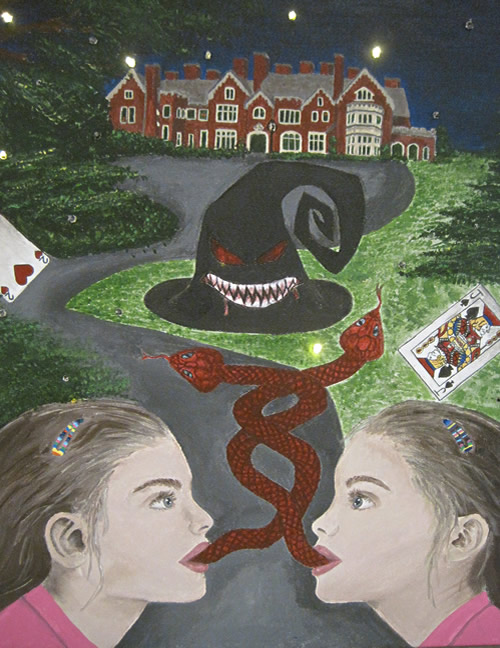

“We found that young people were especially keen on the stories in Pretty Monsters,” the organization said in an interview with Arts Midwest. This appeal to young readers was perfect for Read Imagine Create, a program for middle and high school students who were given a free copy of the book to read and discuss in their classrooms and then were tasked with creating artwork inspired by the book. The students’ work was then adjudicated by professionals in literary, visual, media, and performative arts and presented to thousands at five libraries.

|

“The ninth grader who won first prize in the literature category for her story ‘Out of One’s Mind,’ inspired by ‘The Wizards of Perfil,’ turned out to be the younger sister of the then-thirteen year-old boy who won first prize in literature in our first NEA Big Read in 2011 with his hysterical poem, ‘The Orangutan,’ (inspired by Poe’s ‘The Raven’). She then entered her story in the San Diego Writer’s INK NEA Big Read writing contest and surpassed all the adult contestants by going on to win the first prize again,” the organization said. “Teachers have told us again and again how important it is for students to be recognized for their creations, especially those not based in academics. One teacher tells us every year how important it is to put copies of the books into the hands of her students who, in many cases, have never owned a book of their own.”

Read the full interview and view a sample of student works at Arts Midwest’s blog.