Continuing the Tradition

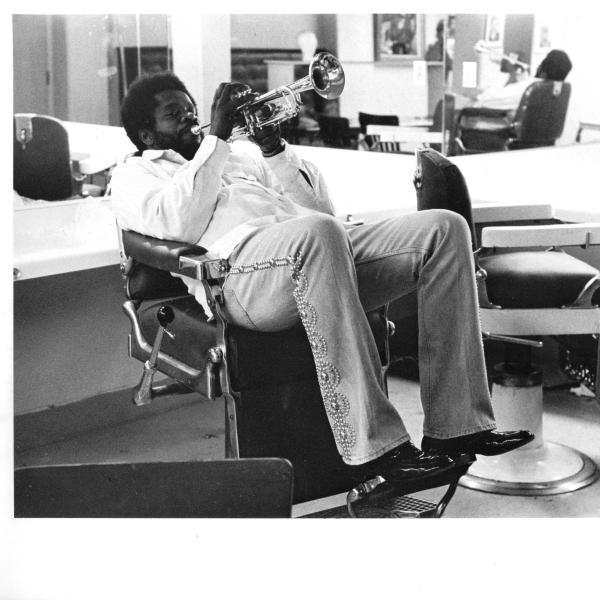

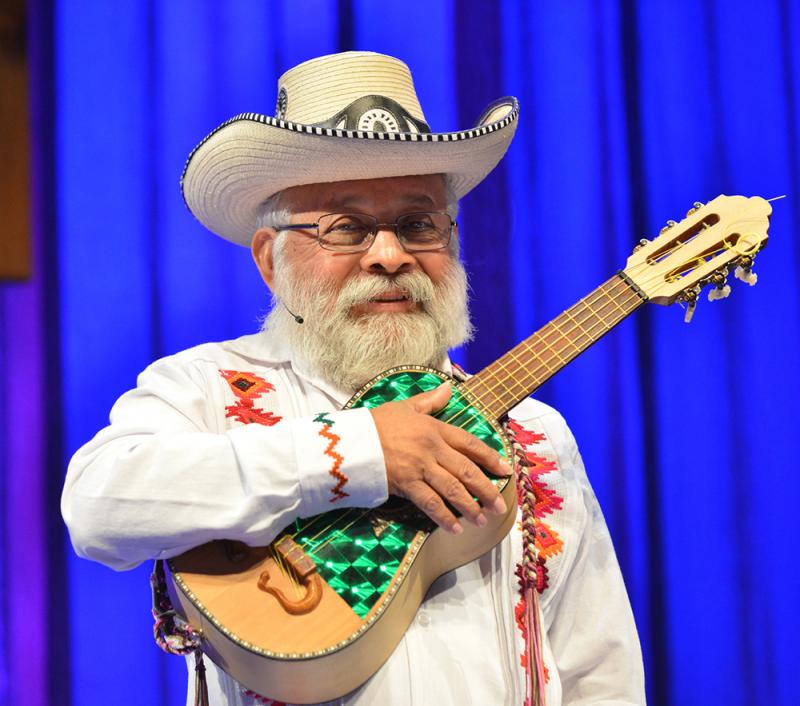

“I don’t know why I was drawn to the son huasteco,” recalled 2016 NEA National Heritage Fellow Artemio Posadas in an interview with Daniel Sheehy in 2005. “I believe it was the falsetto that really got to me, along with the profundity of its poetry.” Son huasteco, also called huapango, was born in the Huastecan region of northeastern Mexico (where Posadas is from) in the late 19th century, and is performed by a trio consisting of violin, jarana huasteca (a small guitar), and the quinta huapanguera (a large guitar). Usually two of the three musicians will sing short, often improvised, lyrics that follow traditional poetic forms, alternating between them. Melodies are punctuated with high falsetto as the violin often tears off into wild ornamentations.

In a 2013 documentary directed by Roy Germino called The Mexican Sound, music producer Mary Farquharson describes the music style as having “a tremendous intensity. It’s the Mexican specialty of a very painful joy or a very joyful pain.” At son huasteco gatherings, people dance in a clearing or on a wooden platform, their footwork combining with the music to create a rhythmic conversation between dancers and musicians. In recent decades, it has also created a conversation between and across geography and age. The music is gaining popularity, especially among Mexican-Americans in areas of California, engaging young people and binding together generations. One of the driving forces behind its resurgence is Posadas.

Posadas fell in love early on with his native music, studying it at university in San Luis Potosi and from the best practitioners he could find. He learned all three instruments, the traditional songs, and the dance styles. He brought this rich expertise with him when he came to the United States for the first time in 1973, visiting San Francisco. He came back in 1974 and led workshops in son huasteco and son jarocho (another son style from Veracruz, Mexico) to eager students in the Mexican-American community. It was the first time he had taught.

He said of the students who took his early classes, “For those who did not have Mexican heritage in their background, this was an opportunity to learn another cultural practice. But for those who had Mexican ancestry, this was simply a way to reconnect to their heritage, back to Mexico, which in 1973 was highly desired in Mexican-American, Chicano communities.” In 1979, Posadas made the Bay Area his home and later became a United States citizen.

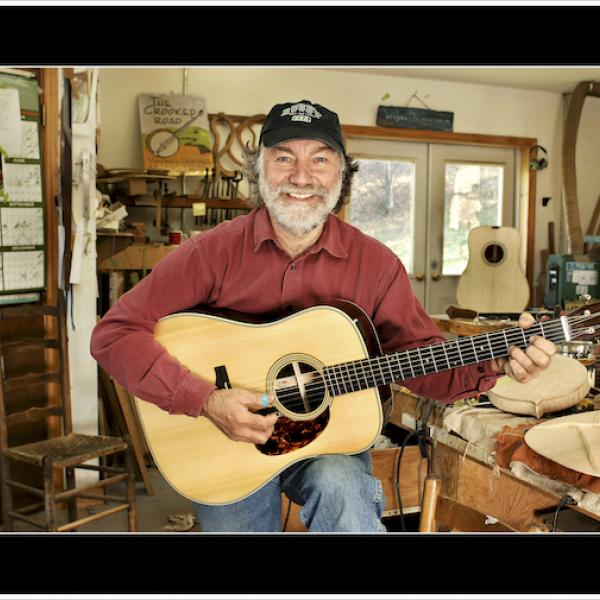

One young person that Posadas worked with closely beginning in the mid-1970s was Russell Rodriguez. For about three years, they practiced together. Then in 1981, Rodriguez was awarded an apprenticeship grant through the NEA’s Folk Arts program to work with Posadas on son jarocho, developing his skills on the requinto jarocho, a guitar-type instrument. After the grant period ended, they continued to play together even after Rodriguez shifted to mariachi music. Rodriguez noted, “I still consider our apprenticeship vibrant, I continuously look to him for information, performances, and to share conversation.”

|

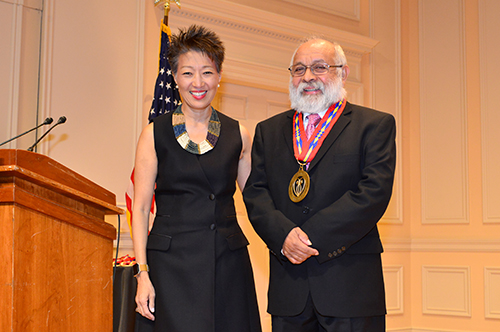

Posadas has mentored other apprentices, including Dolores “Lolis” Garcia who is now an experienced performer and cultural leader in her own right. His current apprentice is Jorge Beltrán. Together they are exploring the poetry of son huasteco, a side of the tradition less often studied than the music and dance. The Alliance for California Traditional Arts (ACTA), an organization committed to supporting cultural traditions through grants and other programs, has supported these mentorship opportunities with Posadas through their own apprenticeship program. And in turn, the NEA has funded ACTA’s apprenticeship program each year since 2002.

In addition to modeling the technique, style, and feelings of Mexican son, Posadas has brought Mexican musicians to the U.S. so that his mentees could interact with them. He also took students with him to Mexico so they could see the music in its natural environment. Rodriguez said that by seeing how the music is celebrated in Mexico, Mexican-American students could understand how the music “provides different kinds of sentiment, because sentiment comes not only for those playing it but also those who are singing and dancing along. Artemio worked very hard to make sure we experienced those things.”

Through these one-on-one musical relationships, whether formal apprenticeships or simply the consistent practice between mentor and mentee, not only is technique passed on but deep cultural knowledge as well. Posadas noted that “those who have participated in an apprenticeship program will be those who continue the tradition, who will be the cultural leaders who make sure that this practice stays vibrant and work to amplify it or to explore other aspects of it.” As a perfect example, Rodriguez is now program manager for ACTA’s apprenticeship program.

In 1990, Posadas began an ongoing relationship with East Bay Center for the Performing Arts in Richmond, California, teaching son huasteco, son jarocho, and other styles. The center has 600 students at its main site and about 4,500 in programs in 22 Title I public schools. In addition to teaching at the center, Posadas and his longtime mentee Lolis Garcia participate in professional development training for teachers, focusing on integrating Mexican son into academic subjects, creating units to promote ESL teaching and English and social studies.

Jordan Simmons, the artistic director of the center, said Posadas “has raised a generation of artists who are themselves teaching in the academy and in the community. He has influenced hundreds and hundreds of students.” But Posadas is quick to credit others who have helped keep the tradition alive and vital. In addition to Lolis Garcia, Jorge Beltrán, and Rodriguez, Posadas cites Rosa Flores, Ricardo Mendoza, and Lourdes Beltrán.

Further increasing the music’s popularity is the demand for it at social gatherings. Posadas noted, “Now that there are more people familiar with the music [in the U.S.], there are more gatherings, like in a fandango. People practice, engage the tradition, and in that space they are really enjoying themselves and learning through participation. It’s not that they have to dance or sing. It’s simply their presence there.” He continued, “The music serves as a kind of tool or a conduit to connect to the heritage, to the roots, but it is also something that connects young people to the older generation, their parents and other family members who might have grown up in Mexico or still keep certain traditions. This is a key link in the chain to make it whole or complete.”

|

Amy Kitchener, the executive director of ACTA, observed, “What I think is so interesting about this sones Mexicanos movement is that it’s participatory and when you think about the arts nationally and what’s been happening over the last decade, there is the move from observational kinds of engagement to more participatory engagement. This form so exemplifies this deep type of participatory art-making.”

Posadas said, “The music even in its most traditional manner seems to be fresh because of the context in which we live, just the bombardment of so much commercial music from all sides, radio, TV, the Internet. Because it has its own nuanced freshness, it stands out on its own.”