From the Archives: The State of the Folk Arts

Today at 5:30 pm we honor the 2016 class of NEA National Heritage Fellows with a public awards ceremony at the Library of Congress. On Friday at 8:00pm ET we will continue the celebration with a free concert at George Washington University's Lisner Auditorium, which will also be webcast live on arts.gov. We invite you to join us for both of these celebratory events, and you can find more information about how to participate here. As we prepare to honor these master artists in the folk and traditional arts, we thought it was fitting to republish NEA Director of Folk and Traditional Arts Clifford Murphy's June 2016 post on why the folk and traditional arts are so essential to our communities.

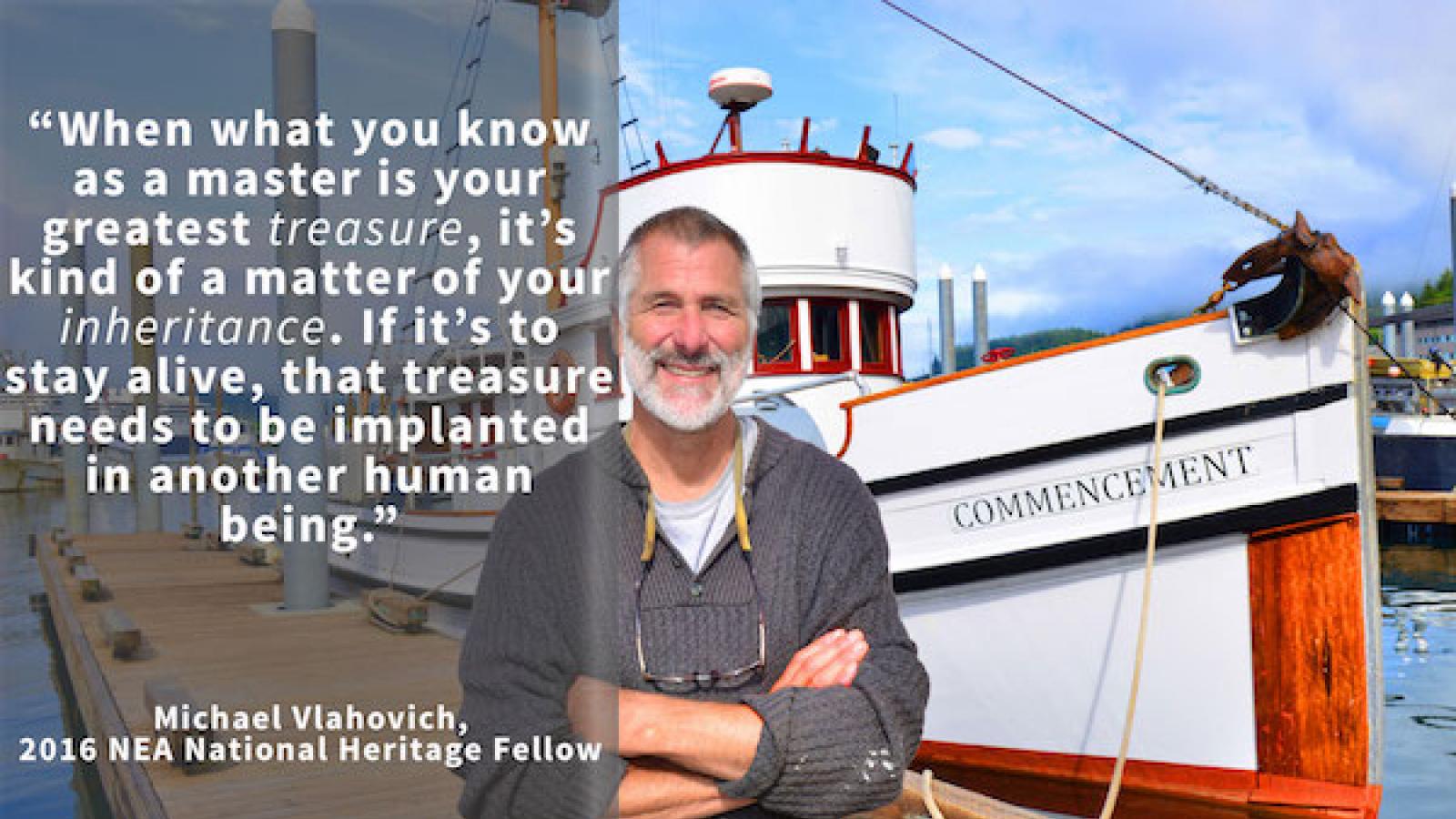

The announcement of a new class of NEA National Heritage Fellows is always a time for reflection on the stunning vibrancy of the nation’s folk and traditional arts. It is also an emotional, joyous time. For many of the fellows, the congratulatory phone call that they receive catches them entirely unaware. After all, they have not applied for a grant, or personally requested recognition: behind each fellow is a group of advocates – community members and folklife professionals – who have nominated these extraordinary stewards of living traditions. And while the National Heritage Fellowships are a time to reflect on a lifetime of accomplishment, they are also, to paraphrase 2015 NEA National Heritage Fellow Dan Sheehy, a recognition of masterful individuals whose primary focus has always been on the future.

NEA Heritage Fellows are, by and large, negotiators and crafters of cultural identity, and we can look to them as guides through tumultuous times. Even the most cursory glance at local, national, and international news reveals that debates about identity – cultural, religious, racial, gender, political—dominate our everyday discourse. Identity is both what we celebrate and what we fight about. And for communities in crisis—places as different as my hometown of Baltimore, Maryland, and the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota—coming to grips with our complicated, overlapping, and conflicting cultural identities is seen as a critical step toward community healing and rebirth. For folk and traditional arts professionals—whether we are folklorists, curators, community artists, administrators, or educators—this space of community and identity is precisely where we work, and in that lies the opportunity to make ourselves truly useful.

Since the inception of the NEA’s state folklife programs in 1974, state folklorists and folklife nonprofits have made a qualitative case for relevancy. For nearly a half century now, we have argued for the need for cultural equity—Alan Lomax’s idea that “cultural diversity is as essential for human survival as biodiversity”. This is the intellectual legacy of both Alan and his sister, Bess Lomax Hawes, who was the longstanding director of folk and traditional arts here at the NEA. With this as our foundation, it feels we now stand perched on the doorstep of a new era for the field—one which draws upon both our ethnographic sensibilities and our understanding of civic institutions to facilitate and mediate patient, practical community problem-solving and community programming.

Over the past decade, there has been a growing demand for relevancy placed upon our cultural institutions. For many, it is no longer acceptable for our cultural institutions to program at communities; instead, new models of programming with communities are emerging. Again, this is the space in which folk and traditional arts professionals have been actively working. We provide valuable public service by visiting with the public (ethnographic fieldwork) and facilitating collaborative interpretation (cultural programming and curation). The NEA provides over three million dollars annually to support folklife initiatives nationwide – from statewide programs such as the Oregon Folklife Network (over 40 states currently have state folklife programs), to cultural festivals of breathtaking scope such as Tucson Meet Yourself, to online journals such as Mississippi Folklife, to the First Peoples Fund’s “Rolling Rez Arts Bus” at Pine Ridge, to the New Neighbors Music Project at the Vermont Folklife Center, to Grammy-nominated field recordings from the Upper Midwest (Folksongs of Another America), to City Lore’s Artists in the Urban Classroom program in New York City’s public schools. On the whole, these NEA-funded initiatives serve as a varied and quantifiable indication of the size and scope of a folklife infrastructure and workforce that is far more robust than existed during what is considered by many to be the golden ages of folklife work in the United States (the New Deal, and the post-Roots/Bicentennial period of the ‘70s and ‘80s).

And, yet, we continue to be a well-kept secret.

Our opportunity here is to capitalize on our field’s great asset—the very real relationships that our folk and traditional arts programs have built with cultural communities over the course of decades. These relationships are most compellingly represented in the faces and masterful artworks of our NEA National Heritage Fellows. But most practically, our field has built and maintained extensive community and institutional networks, as well as deep ethnographic fieldwork archives and cultural analysis. These are assets that are largely unique to our discipline, and which are desperately needed by our fellow travelers in the arts and civic institutions.

We hope you will join us in celebrating and congratulating this year’s National Heritage Fellows, and we thank each of you in the field for the advocacy that has resulted in the recognition of 413 fellows since 1982!