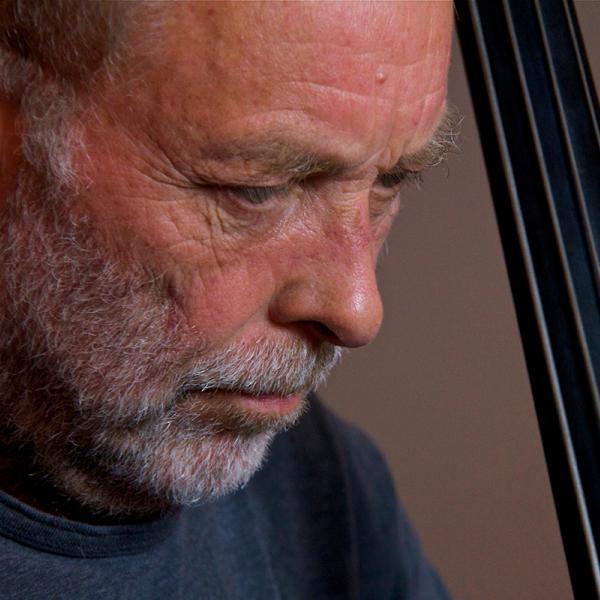

Billy McComiskey

Music Credits:

The Independent/Rabbit in the Field from “Makin’ the Rounds” by Billy McComiskey

Written and published by Billy McComiskey

© & (p) 1981 Green Linnet Records/ Compass Records Group

Courtesy of Compass Records Group

Flowers of Brooklyn/ The Palm Tree from “Makin’ the Rounds” by Billy McComiskey

Written and published by Billy McComiskey

© & (p) 1981 Green Linnet Records/ Compass Records Group

Courtesy of Compass Records Group

The Music Book/ Bela Bartok’s from “Trian II” by Billy McComsikey, Liz Carroll, and Daithi Sproule

Traditional / Public Domain

© 1995 Green Linnet Records (p) 2007 Compass Records Group

Courtesy of Compass Records Group

Jo Reed: You’re listening to button accordion player and 2016 NEA National Heritage Fellow, Billy McComiskey, and this is Art Works, the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

There are three important things to know about Billy McComiskey. One, he’s a terrific button accordionist who plays traditional Irish music. Two, although he was born in New York City, he’s largely responsible for the robust traditional Irish music scene in the Baltimore-Washington area. And three, his focus is always on relationships. Ask him if he came from a musical family, and you’ll find out the name of the teacher who taught the teacher who taught his grandfather back in Ireland. Mention a piece of Irish music you like, you’ll get a history of the tune and the differences in the ways that it’s played in Mayo, Galway or Donegal. And compliment him? You’ll get a litany of the great players who came before him as well as the younger ones coming behind and what he’s learned from each. For Billy McComiskey, everything is connected, and he’s part of a much greater whole – just doing the best that he can.

Well the best Billy McComiskey can do is very good indeed. He was part of two legendary groups, The Irish Tradition and then Trian. In 1986, he won the coveted All-Ireland Championship for the button accordion. His 2008 solo CD, Outside the Box, won the Irish Echo’s album of the year, and the Echo named him its Traditional Artist of the Year in 2011. And Billy McComiskey is a master in the Maryland Traditions’ apprenticeship program, teaching younger players about traditional Irish music. And let’s not forget, he accomplished this as he was working a full-time job and raising three sons with his wife Annie. It goes without saying, it’s a home filled with music.

Jo Reed: How many accordions do you have?

Billy McComiskey: <laughs> I don’t know. It’s somewhere around a dozen and yeah, they’re thrown all over the house. Two of my three sons are very good players. So they end up bringing up boxes in. That’s what we call them. They’re called boxes. Over here I guess – I hear the expression, “Oh, you play the squeezebox,” and I guess, yeah, I do play the squeezebox, but we don’t call it a squeeze. We just call it a box.

Jo Reed: You grew up in New York City.

Billy McComiskey: Yeah. Grew up in Brooklyn. Yeah.

Jo Reed: Tell me about your growing up. Was it a musical household? Did you hear music a lot? Did your parents play?

Billy McComiskey: It was all about music, but it wasn’t just about music – it was about Irish music. My grandmother, Nora Sweeney, was a step dancer, and all her brothers played a little something. Maybe they all had flutes and fiddles, and if they didn’t do that they’d sing, and they’d enjoy a bit of a jar, as they would say. And my grandfather though, he was like a pretty quiet fellow, and he loved to dance. He was a step dancer, and he loved to play the fiddle and was very, very good. My mother, she was Mae McComiskey, she was an Irish step dancer and her two brothers, Matt played the accordion, and Andy was a flute player, and they all had – everybody had – regular jobs, that kind of thing, and managed just living there in Brooklyn. And my father came out, – oh, I guess it would be 1948 – right around the time this accordion was built. My father came out from North Ireland. He was an Irish Catholic when World War II was kind of getting to a fever pitch. My father and his father talked about just the state of affairs in Ireland and England, and they knew what was going on in England with the colonialism. They knew that it was wrong, but they also knew that Hitler had to be stopped. So somehow or another – I don’t know how he did it – somehow or another my father ended up in the Queen’s Royal Air Force, a pilot, and he was a farmer, not a particularly well-educated man. The Irish Catholics in Northern Ireland got whatever education they could, but somehow or another he got – flew, flew the Lancaster bomber and the Spitfire. And he trained here. He trained in Oklahoma, and when he got a look at the land and the scope here he decided if I survive I’m coming back, and he did, but he never made it out of Brooklyn. He went out to his aunt’s house in Brooklyn, and there was a row house for sale in Brooklyn – in downtown Brooklyn – and somehow or another he came up with the money and bought this house. This is something that Irish people, especially Northern Irish Catholics, cannot do. And he saw it, and he bought it, and he started a little hardware store for himself, and he eventually worked as a maintenance mechanic. He lived by his wits. He was one of the greatest immigrants.

Jo Reed: How old were you when you started playing, or when you first picked up the box?

Billy McComiskey: Well, the first time I remember doing a gig was at my uncle’s house up in the Catskills, and he’d have these house parties in his boardinghouse. He didn’t charge anybody to stay there, but if you could sing or dance or you’re a bit of fun then you enjoyed it. He’d just give you a room, and then everybody would go, and there would be a bit of a party and so he was planned. I was five or six, and he said, “Do you want to help me with this?” And I said, “Sure, sure.” And so he handed me two spoons, and I just rattled away behind him on the table with the two spoons, and I just absolutely loved it.

<music>

Jo Reed: So you loved making music from an early age. When did you actually start playing the accordion?

Billy McComiskey: My cousin, John Sweeney, he went to Germany, he was in the navy, and while he was in Germany he brought back a little Hohner accordion, and it had a little black button on it, and I always just thought that was the neatest thing, and he showed me the couple of tunes that he knew on it. He leaned more toward the fiddle himself, but he was able to get me started, and then without saying anything he just left the accordion there and, he was just the nice – just the nicest guy.

Jo Reed: After that were you largely self-taught? Was there anybody who really taught you when you were younger?

Billy McComiskey: The funny thing about it was, for the little bit that I learned from John, it was enough to get started, and we would go to the clubs. It’s not like you could just go out and get a music lesson. I think I was about maybe ten and pretty stone mad for it, I loved it, and I mean I would go up to my uncle’s house. My grandmother would take me out to the music clubs, and my mother and father were always having house parties, and I remember when I was about ten or eleven hear – eleven – hearing this man named Joe Cooley. He was one of these charismatic individuals. He was a box player from County Galway, and somehow or another he ended up in my godfather, Pat Murphy’s, bar in the Catskills, and that was it right there. It was a done deal when I met Joe Cooley. He was a really phenomenal individual. And maybe two or three years after that I met a man by the name of Sean McGlynn. Sean McGlynn was from East Galway, a carpenter by trade. And this here – this is his old accordion. There’s a couple of buttons sticking on it now. I dropped it.

Jo Reed: You became a devotee in the East Galway style of playing.

Billy McComiskey: That’s right, yeah.

Jo Reed: Can you explain what that is and maybe give us a demonstration of what that is?

Billy McComiskey: Yeah. As it turns out, as they look back on it now, it’s regarded in this broader perspective now so it’s kind of now called the Slieve Aughty style. So there was two guys. There was Joe Cooley, and there was this other guy, Paddy O’Brien from Tipperary, and they both played in this incredibly good band at different times – the Tulla Ceili Band. It was Joe Cooley that brought Irish traditional music to the public’s eye here in America. When I heard him in the Catskills, every player in Boston, New York City, anywhere within a hundred miles – and that was kind of a lot back then – just came. This was no Internet, no advertisement, nothing, but in our community, in the Irish traditional music community, they heard that Joe Cooley was going to be there and so everybody just went. You could see why they went. It was like meeting a great statesman; it was just an incredible experience. Paddy O’Brien kind of stayed at home, and then he came here for a little while. He got a job in New York City driving a bus, and so he had two reputations. Not only was he arguably the greatest of the Irish accordion players to ever live, he was also the worst bus driver ever to drive in New York City. So he said – he just went home. He gave it up, and he went back to Ireland. So this thing went on. He never had a formal music school, Paddy O’Brien, but he taught, and he influenced so many players, and he taught kids to play in bands, these dance bands – they call them ceili bands, accordions and fiddles and drums and pianos. Really they put the hair standing on him, but he was a brilliant composer as well.

Jo Reed: What is the East Galway style?

Billy McComiskey: I got completely sidetracked there. So they kind of called it the East Galway style because of Joe Cooley, and then this other brilliant accordion player, who is also alive and well now, the great Joe Burke, and there was another one, Kevin Keegan, and Sean McGlynn, my own mentor. So these guys played this old music from Ireland. The amazing thing that happened around 1950 is these guys figured out how to play this old music from the 1600s, 1700s – it really goes back. Turlough O’Carolan, the harper – the great harper and composer – people started writing his music down in the early 1700s. Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, they refer to it, was just raging with music. It’s what the Celts did. It’s what they love to do; it’s how they express themselves socially. East Galway music in general is kind of long and it has -- <plays music> -- if that makes any sense. There’d be maybe flat sevens mixed in with regular sevens. A triplet would become a roll, instead of three notes it would be five -- <plays music> -- and how does this all fit? How can you take this little instrument and make it sound compatible with these instruments from 200 years ago?

<music>

Jo Reed: When you were younger, and you were still living in New York what was the music scene like then, the Irish music scene obviously?

Billy McComiskey: There were a handful of older players that had immigrated out here in maybe the 20’s and 30’s, and they’d managed to make a living in New York and as, like the song goes, if you can make it there – these guys, these were hardworking men, they’d have jobs, and they’d play when they had a chance. And it’s always been the same thing. Everybody’s played because they love it. So my grandmother and my mother, Mae McComiskey, they would take turns. They wanted to make sure that I was able to get out to hear the music because I had to hear the music. I had to so—

Jo Reed: That’s the way you learned.

Billy McComiskey: It’s how I survived as a human being. I had to hear the music. So we went to these musicians’ clubs, and it would be maybe in the back room of a bar. The old Rainbow Café was on 39th Street and 5th Avenue in Bay Ridge. It was a pretty good pizza parlor, very handy, and every Sunday afternoon the musicians would go there. It was maybe 25 cents admission at the door. So that’s how I got to hear the players, and when I went to Ireland I noticed – in 1970 when I first started to go over for the festivals and whatever was going on or competing I noticed over there – it was the same thing. It was these clubs in these back rooms of hotels or something like that. Irish music was kind of frowned upon in Ireland and in the United States. People associated it again with colonialism, poverty, war, tragedy. There was an awful lot of sadness amongst the Irish.

Jo Reed: Billy, will you describe sessions? I mean, I know it’s when Irish musicians get together and play, but can you kind of describe what goes on in them?

Billy McComiskey: So a session would be – these people were like enormously talented, and it’s an oral tradition so they didn’t know how to read music, they didn’t know much about music theory, and they’re, “Paddy no – how do you have to – how do you turn the second part of that tune?” “Turn” would be, “How does the second part of the tune go?” and you’d just sit – a fiddle player and a flute player would sit and they’d be negotiating a little tune. And I remember like it was yesterday sitting with Sean McGlynn, and we were trying to figure out how to play this Martin Wynne fiddle tune, and in the course of two bars it covered two and a half octaves. It really took a long range on it, and we were trying to figure out how to finger this tune – it’s kind of like how a pianist would do – myself and Sean McGlynn. And when we finally got it Sean says to me, he says, “There’s the difference right now,” and he says, “They’re all down in the bar singing and dancing and having a great time, and here we are sitting in the kitchen worried about one note.” <laughs> The way they would discuss the music, and, or, “I – Well, no, you have that all wrong.” So you’d meet these guys, and the next thing, “Well, we should try, we’ll have a session,” “I think he’s – that usually,” <inaudible> “We’re going to have –,“ and you’d have to sit down and try to find out what you have in common because it’s just very, very important. And to keep yourself calm you’d have a little something to drink and then there would – the next thing would be the next day. That’s what a session is.

Jo Reed: From what I understand, and you can please correct me if I’m wrong, it’s a little more structured than jamming with everybody just doing this kind of free-for-all.

Billy McComiskey: Yeah, yeah. A tune, say – if the button doesn’t stick on me – <plays music> so that right there is that Martin Wynne tune that we were trying to figure out, how does this tune go? How can we make that work on this accordion? That is how the tune goes, and then when it turns, <plays music> it kind of resolves on this sixth note, this kind of B minor note, going “What-- why? I wonder what he was thinking.” I don’t even know if Martin Wynne knew how to write a tune with paper, but he knew exactly how he wanted that tune to sound. And so then, how does the bowing go? What was he thinking there? And Irish music, it’s been around a really long time and people, and it’s a labor of love that people have been trying to keep – they’ve been trying to keep this art intact for many centuries, and it’s an awful lot of fun doing that. It’s just a tremendous amount of fun. So and then if a tune has a way that it goes, then that’s a lovely thing. Maybe the fiddlers in Donegal would shorten the bow a little bit or the box players would have an extra-long note or a roll would go here. Just a lovely social thing.

Jo Reed: Now you took that lovely social thing in some ways and you brought it down here. For years you were part of a trio, as you mentioned, playing Capitol Hill. The Dubliner is part of the Irish tradition.

Billy McComiskey: That’s right, yeah.

Jo Reed: Tell me about that experience. What was it like playing there?

Billy McComiskey: It was chaotic, and it was pretty much through the roof.

Jo Reed: What year was this?

Billy McComiskey: 1975.

Jo Reed: Okay. And was there Irish music down here then, or were you really bringing it in some ways?

Billy McComiskey: We brought it. Lou Thompson was living down in Washington, and he was talking to the manager. In The Dubliner they were trying to figure out, “What can we do to make this really authentic?” They wanted the traditional music. They wanted the old music. They wanted the sessions. They wanted everything that Irish music truly is. They knew that they could find musicians that would want to come to – would jump at the chance for – a gig like this because The Capitol building was right there.

Jo Reed: Lou Thompson and Peggy Reardon knew exactly where to look and who to look for.

Billy McComiskey: They actually came up to the Bronx. I was playing in a place called the Bunratty Pub, and they’d pay you $50, and you could have all the Heineken you could drink, and that was the deal. So they came up to the Bunratty because I had a reputation for – I wasn’t <laughs> very businesslike. I’d go out to play at a feis, a dancing thing, and then wander off and end up in a music session. So they kind of thought well, this is our guy; this is what we want. And I said to them, “Well, you can’t play that. You can’t play Irish music in an Irish bar. You can’t do that. If you’re in an Irish bar, you do Irish drinking songs or Irish American “Danny Boy” songs, stuff that, but they decided no, this is – well, this is what Irish music has been for centuries, and I said, “I think if you go,” and they were thinking if we can do that, and if you guys can pull it off, and then that’ll be authentic, and then the bar will do good, and everything will be terrific.

Jo Reed: And they were right.

<music>

Jo Reed: Billy McComiskey formed The Irish Tradition with fiddler Brenden Mulvihill and singer-guitarist Billy O’Brien, and the trio headed for The Dubliner in Washington DC.

<music>

Billy McComiskey: We just went in there, and it just kind of started to work, and the next thing WGTB, the Georgetown University station, started having a Celtic music show on, I think it was, either Saturday or Sunday. Between that show and just the bar was really good. You could go in there, and there’s an awful lot of attorneys and their aides, and, Ted Kennedy really and Tip O’Neill, these guys, they really enjoyed it. If you’re going to have a bar, these are the guys – these would be the Irish American guys you’d want in it. Just, we were oblivious. We didn’t even know what was going on.

Jo Reed: And just like that, Irish music found a new audience in Washington.

<music>

Jo Reed: And along with politicians and journalists, people from the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Arts were paying attention and liking what they were hearing.

Billy McComiskey: The other thing that was remarkable, I think, was between the Smithsonian, the Smithsonian Folklife Festival – the Smithsonian, all of a sudden they’re like, “Oh, oh, oh, sure. We love Irish music.” And guys, Alan Jabbour and these guys from the National Council for the Traditional Arts, they’d just be kind of sitting there having a beer. They’d just walk across the mall and, “Oh, there’s a nice bar over on F Street,” and it was just an amazing –

Jo Reed: So it gave you an audience that was so broad.

Billy McComiskey: Broad. Very, very bright, and these were the pioneers – these folklorists, the ethnomusicologists, these were the guys – Joe Wilson. These were them, and Joe Wilson, he came up to us, and he said, “You guys sound like a bunch of old farmers up there. I love it,” and he was such a nice guy, so genuine. But we didn’t know how fascinating it was. We kind of had an idea of how lucky we were, but we were just having way too much fun, and there was a lovely kind of hip scene going on, kind of like a parallel to what was going on in Dublin at the same time.

Jo Reed: The Irish tradition played at The Dubliner for three years, and the trio remained together for 12.

Billy McComiskey: In the course of that, I met my wife from Baltimore, so I kind of moved out of D.C. to Baltimore. Now, there is a lovely scene, sessions and gigs and concert work in D.C. and Baltimore is spectacular.

Billy McComiskey: Well, for my own sanity I kind of had to do it. I got myself a trade first, and I was able to get a modest little job, and I worked the job for 26 years. I guess the beautiful thing about the music is it’s self-sustaining, and you fall in love with it. You have to have it. It becomes who you are. So by the time I moved up here there was a bar, – a couple of Vietnam vets opened a bar in Pigtown – and the bar was called the Gandy Dancer, and they actually had a liquor license, and they were licensed to have live music, and they could even have dancing so it was a kind of cool thing. It kind of blossomed into ceili dancing –

Jo Reed: And ceili dancing is social dancing.

Billy McComiskey: Ceili dancing is kind of nineteenth-century organized social dancing. There’s a whole set dance scene in Ireland just tens of thousands of people that do these dances all over Ireland. And that caught on in New York City, and then it ended up catching on down here. The funny thing about down here, and I guess it’s because of all this interest in folklore and this whole scholarly way of approaching Irish music. It’s the more progressive music scene in this area. It’s not driven by Irish immigrants. It’s not driven by old-world values. What goes on in the mid-Atlantic area here is kind of Irish music at a very high standard, and the dancing has gotten pretty good too. It’s social dancing, but it’s a very high level of social dance and there’s a lot of footwork—

Jo Reed: And you started a ceili band.

Billy McComiskey: Yeah, down in Washington, there are all these young players. They’re all hippies and all college kids and all that kind of thing, and when they came up here, there’s kind of more of a working-class kind of bunch of people doing it, but again it was kind of the same motivation. So I figured we can put together the Baltimore, Washington Ceili Band. It just sounded like a big, long name, it reminded me of the “Little Rascals” or something, and we did the best we could. We actually won the Comhaltas competition for the North American championship, and I was going to try to bring the band to Ireland, but it was like herding cats. It’s impossible. So I went over myself. It was 1986, and I just went over as a soloist, and I won in 1986.

Jo Reed: Yes, indeed you did.

Billy McComiskey: Yeah. So that was pretty cool.

<music>

Jo Reed: You were part of another legendary trio, Trian?

Billy McComiskey: Trian, yeah.

Jo Reed: With Liz Carroll, another Heritage Fellow.

Billy McComiskey: <laughs> Another Heritage Fellow, yeah. And Daithi, Daithi Sproule, he was the singer, guitar player.

Jo Reed: I should say, you did three CDs with Irish Tradition--

Billy McComiskey: Yeah, three with the Irish Tradition, which was unheard of at the time, yeah.

Jo Reed: And two with Trian.

Billy McComiskey: Two with Trian, and it was all new compositions that we’d come up with.

Jo Reed: Yeah, and you’ve written 30-plus songs?

Billy McComiskey: Yeah, I guess they’d be called tunes.

Jo Reed: Tunes.

Billy McComiskey: Yeah, and I –

Jo Reed: When did you start writing?

Billy McComiskey: I guess the trick was, when did I start putting them down because I was always making up tunes.

<music>

Billy McComiskey: I had written a jig and a hornpipe and Sean McGlynn, who was a very, very positive kind of guy, and he said, “Would you show me those couple of tunes that you wrote?” And I did. And so the two of us would sit and play. “They’re lovely tunes. You should write more,” this was what he said. And when the great Paddy O’Brien came out from Tipperary, I was sitting on the stage playing my tunes with Sean McGlynn, and Larry Redigan, our great Dublin fiddler, a very prolific composer, he was in the back talking with Paddy, and the next thing Larry Redigan came up, and he whispered something to Sean, and then he went off again. And Sean just goes, “Come on. We’ll play some more” and I said, “Well, what did Larry say? Are we playing up here too long?” and he said, “Larry came up to tell me that Paddy O’Brien loved those tunes you wrote.” How gentlemanly and subtle ‘cause that’s such a really beautiful, simple little thing, and here I am 50 years later, and I still treasure that instant in the music. It was such a lovely thing.

Jo Reed: And you were named a 2016 National Heritage Fellow. Has it sunk in?

Billy McComiskey: <laughs> It’s really nice. It’s a lot of fun. Yeah.

Jo Reed: And true to form, ask Billy McComiskey for his thoughts about receiving the 2016 National Heritage Award, and he immediately talks about a great player who came before him.

Billy McComiskey: m: I actually get emotional when I think about it. I met Joe Heaney. I don’t know if you’d be familiar with Joe Heaney. Joe Heaney was a maintenance man in Brooklyn, and he loved to sing. He was a Connemara singer, and he was a collector of what they called Sean-nós songs. So I actually got to play at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. I don’t know – was it 1975 or 1976 – and here was the very first National Heritage Fellowship recipient, Joe Heaney. He had given songs to the Clancy Brothers, and this whole time he was just a maintenance man, and we sat there in awe. I remember Andy O’Brien couldn’t talk; he couldn’t do anything. He was so in awe just being there with him, and he was just such the gentleman, and we just couldn’t get over what a decent – and then when he sang it was like – and all of a sudden in the course of a week everybody knew what Sean-nós singing was and what role it played in Irish traditional music, and the National Heritage Fellowship has everything to do with that, has everything to do with that. He’s the first one. That’s what the National Heritage Fellowship is.

Jo Reed: Congratulations, Billy. I’m so glad. So many congratulations.

Billy McComiskey: Well, thank you.

Jo Reed: Thank you.

<music>

Jo Reed: That is 2016 National Heritage Fellow, accordion button player, Billy McComiskey. You can find out more about Billy and the other eight recently named heritage fellows at arts.gov. And stay tuned for details about the September 30th Heritage Concert. You’ve been listening to Art Works. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

<music>

Transcript available shortly.

Building a community for traditional Irish music.