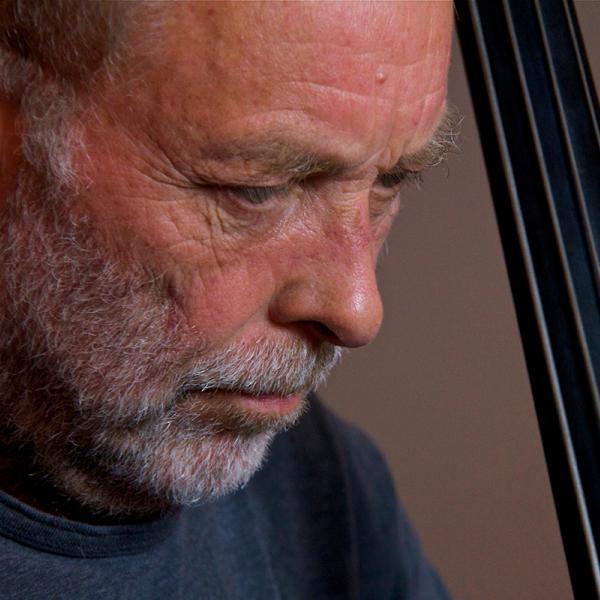

Bowman Wright

Bowman Wright: That’s what theatre is. It’s just life transformed into – to performance and it needs a community. It needs people. Theatre needs people, and people need theatre.

Jo Reed: That’s actor Bowman Wright and this is Artworks, the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I'm Josephine Reed. As Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday nears, I began thinking about Dr. King and the arts— particularly the ways he’s been portrayed in so many different media—the subject of paintings and sculptures, of poems, books, plays, and films. And I wondered how an actor would approach a role like Martin Luther King Jr.—someone who is so well-known and who also touches most of us in a deeply personal way. And then I thought of Bowman Wright who I had seen portray Dr. King in two different plays; The Mountaintop and All the Way—both at Arena Stage. I hadn’t even realized it was the same actor until I read the playbill. As you’ll hear, Bowman Wright is a man who loves the theatre deeply and who believes in its capacity to build community. And as an actor who does regional theatre throughout the country—he’s witnessed that community-building first-hand. Meet Bowman Wright—a young actor and a new father, talking about his passion for theatre and bringing Martin Luther King Jr. to life on the stage. But first, a little background….

Jo Reed: Bowman Wright, tell me about you. Where were you born? Where were you raised?

Bowman Wright: Well, I was raised in Newark, New Jersey... in a inner-city area. My dad’s from South Carolina, so I got a lot of Southern roots in me, and I spent a lot of time down in South Carolina-- Newberry, South Carolina. My parents both are ministers. My father’s a-- used to be a preacher. My mom’s a evangelist minister.

Jo Reed: So there was, I would imagine, music in your house when you were growing up?

Bowman Wright: A lot of it. Lot of it. My father actually used to have a band. He used to sing. And my mom was a singer, but she sung like with my father a little bit, but mostly in church.

Jo Reed: Now, what first drew you to theatre?

Bowman Wright: Funny thing about it -- I think I’ve always wanted to do entertainment since I was a kid. I knew that. At first, I wanted to be a singer. I was like-- I was crazy over Boyz II Men, so I wanted to have a group, and I wanted to sing like Boyz II Men. So I used to always try to get guys together and I got to high school, and I was trying to get a group together. And there’s this one guy in the group that can really sing. I mean, he was like Luther Vandross kind of singing. And I said, “I got to get him.” So he made a deal with me. He said, “Well, you join the drama team”-- because they was having some trouble getting people to join-- “and I’ll join the group.” And so that’s what I did. I joined the drama team. Long story short, a year goes by. I wind up leaving the group <laughs> and staying with the drama team. And what really started to draw me to drama was the fact that I learned that I can actually be a force in teaching somebody empathy.

Jo Reed: Wait, say more about empathy.

Bowman Wright: Well I mean, I used to always say, you know, when I was a kid, that if people can just feel what other people is feeling, then maybe they won’t be quick to judge other people. And then I realized, I said, “Wait a minute. With this acting thing, you do kind of teach history.” And the best way to teach history, I’ve always found, is to teach empathy first. You have to teach empathy within history, in order for history to really come alive. Otherwise, it’s just facts.

Jo Reed: If you can’t empathize, you don’t go to the theatre. You don’t go to films. I mean, that’s part of the whole pull.

Bowman Wright: Yes, I just went to go see Fences, a couple days ago, that was my first big play that I did. I got my first big equity contract. I played Cory, and so the play means a lot to me. But it’s a play that everybody can empathize with, because it’s such a family-driven play. Also, it’s one of those plays where you can actually watch a family deal with situations that everybody deals with, and you can empathize with it. It didn’t matter if you were, Islamic or Christian or black or white or Japanese. It didn’t matter what nationality you were. You can empathize with a man trying to take care of his kids, or a woman trying to be the backbone of the household, or a kid that has dreams that’s bigger than himself. You can always empathize with that. You can empathize with people not feeling like they have achieved the things that they wanted to achieve in life. But it’s scary sometimes, because in TV and film, sometimes we don’t talk about people anymore while they’re hurt or while they’re broken, it’s so action-driven. Rather than being something that can make people think, make people actually have conversations.

Jo Reed: You’ve done four plays by August Wilson. You’ve done Joe Turner’s Come and Gone; as you said, Fences-- you played Cory; The Piano Lesson; and King Hedley.

Bowman Wright: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Jo Reed: He wrote a ten-play cycle, one play for each decade of the 20th century.

Bowman Wright: Mm-hmm

Jo Reed: So, as an actor, what was it like for you, going through American history with August Wilson?

Bowman Wright: Oh, I’ll tell you something about August. In my opinion, I think he’s... I think he’s -- he’s just an amazing writer and an amazing person. He has a way of seeing the world. Remember that movie Tap, with Gregory Hines.

Jo Reed: Right, Gregory Hines the great tap dancer.

Bowman Wright: And Gregory says-- you know, they say, “How do you come up with stuff?” And he said, “Because it’s all around me.” So he goes outside, and they’re listening to cars go by, and they hear the potholes get hit by something. And you see-- you hear the tapping. You hear the music within the street. And the funny thing is, that’s August Wilson plays. <laughs> It’s exactly the same things. It’s the people. It’s the people talking, it’s the cars moving, it’s the things that’s going on under the atmosphere: what people are feeling and saying, that don’t say, and want to say. And that’s what theatre is. It’s just life transformed into performance.

Jo Reed: I saw you as King Hedley at arena Stage and I really loved your performance of this complicated figure and I was also struck by the way August Wilson really looked at the 1980s and what happened to the black community during that time.

Bowman Wright: Yeah, Yeah, I remember, when we did King Hedley, you know one of the things that everybody was pulling up was about the ’80s, and what the ’80s felt like. Even though I was a baby, there was a feeling in the… in the air that once drugs got heavy into the neighborhoods, the neighborhoods started to come down. And the neighborhoods started to get more violent. And what King Hedley kind of talks about is that, you know, one of the things was that we had lost. We had lost the identity of neighborhood, of taking care of each other. It became dog-eats-dog. You can empathize with King in a sense that you see this man is trying to be all he can be. He’s trying to be good, but nothing is giving him a chance to be good. He’s kind of stuck in the corner, and he’s trying to get out that corner. He wants to be heard. I think that’s what most of August Wilson characters are saying, in a lot of ways you know, “We need to be heard. We need to be spoken to.” And I think history says that for all people that we do need to be heard. That’s why I keep saying that the important thing about theatre is that we continue to have conversation, and create conversation theatre helped me to feel like I can do something about that. It helps me think that I can actually be a person who you can empathize with, that I can teach you about new people that you haven’t thought about, that I can teach you about Dr. King, that I can teach you about characters from August Wilson plays, that I can teach you about players from Shakespeare; that I can teach you about these people, that you can see a different side, rather than seeing your own side to it. And maybe you’ll be able to have a conversation with that person that you’re seeing onstage, and hopefully with me, even.

Jo Reed: It sounds to me that you’re saying when you choose a play it’s very important that you choose something that imparts knowledge to the audience, that teaches.

Bowman Wright: Well yes, -- I think anybody’ll tell you, in any profession, you don’t really want to do anything that you don’t have a thing for, especially with theatre, because you spend two months repeating the same stuff. And you’re living the same stuff for two months – at least two months. Sometimes, if you’re on Broadway, it’s longer than that. Now, I ain’t gonna lie to you, you do things for taking care of your baby and taking care of your family. Everything has a, I’ll call, a level, of how do I choose my roles? A lot of times, it’s the writing, I think the play’s important. Sometimes it’s about working with a particular director who inspires me, or a particular group of people who inspire me. Sometimes it’s pure business. And then sometimes it’s about education, like, “How can I learn from it? Who can I teach with it?” Sometime you do a show like Mountaintop, and they ask you to do it again. And that’s written by you know Katori Hall. But they ask you to do it again, and you know it’s going to be in front of a lot of young people.

Jo Reed: And that’s a play about Dr. King-- his last night alive.

Bowman Wright: Yes, that’s inspiring enough to say, “You know what? If I do my best, maybe I’ll touch a few of them out here in this audience. Maybe a few of them will want to read more about Dr. King and what he was trying to say, or just read more about history-- read more about that time, and maybe they’ll see that history only repeats itself if you don’t actually know it.” And I’m not saying facts. Anybody can know facts. But you have to know history. You have to almost say, “How can I put myself in these shoes? How can I empathize with what these people were going through in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s and ’80s, and stuff like that-- ’90s, even-- so you don’t repeat that, so you don’t teach your kids to repeat that?”

Jo Reed: Since we’re talking about Dr. King and The Mountaintop, Katori Hall’s play, a play in fact that you’ve done twice, how do you approach an iconic figure like Dr. King, who’s so familiar to all of us?

Bowman Wright: Oh, wow. You know, one of the things I did was read a lot. I think I read more on Dr. King when I first did him, first tried to portray him, than I did ever before. The director that first directed me in it, his name was Robert O’Hara. He came to me, and he said, “Listen, I want you to think about the man. I don’t want you to think about the icon. Because the icon is not actually the man. So you have to kind of get what has been taught to you out of your head about Dr. King. So I said, “Well, let me read some of his philosophy.” So I set back and I read a few books on him. I watched a bunch of documentaries. I did all of that. But then I started to think about some of the things that he was saying. And... we like to make Dr. King a saint. But the fact is, he was just a man. And one of the things he always said is that, “I’m not a good man, but I want to be a good man.” And he knew that everybody have flaws, including himself. And he was trying to overcome his flaws in his sermons. So when you watch that play, Mountaintop, you’re watching a real person, not an icon. You’re watching a man who has his demons, and still wants to do good. Everybody has that ability to do good. Everybody has a chance to do something good, even if they have some rocky moments in their lives, and they’re not perfect. So that’s what I learned from him. I learned a lot from him-- a lot from him. I told my wife, “Every time I have a rocky moment in life, somehow Dr. King shows up in my life, whether he shows up-- somebody want me to play Dr. King, or I’m sitting in the house, and all of a sudden this documentary come on, and it’s Dr. King, and he got something to say.” <laughs> So... <laughs>

Jo Reed: You didn’t attempt to mimic his voice at all. I mean, his voice is so distinctive. And you-- and I guess you and Robert O’Hara discussed it, and just said, “No, we’re not going to go that route.”

Bowman Wright: Well, yes, that was the big thing. And it was also one of those things, too, where we both had the same ideas about it. But one of the things is, I felt like that’s not what-- to truly honor Dr. King, he don’t want me to sound like him. He don’t want me to mimic him. What he want me to do, if he want me to do anything, he want me to tell the truth, and he want me to go onstage, and he want me to be me, because everybody has a Dr. King in them. Everybody has a heroic figure in them. And the only way to really do that, the only way to really play a man, is to be a man. And you have to be your own man. And in being your own man, I felt like that would be more effective to an audience, rather than me trying to mimic him. I didn’t want to do a PBS special on him <laughs>. I wanted to do more of a... I wanted to actually affect people in a way that made them think outside the box; not just think about what Dr. King did, but actually what they can do.

Clip from on the Mountain Top

And I look out that back window and saw such blessed peace descended in the chaos. Don’t they know you can’t be marching down the street, bust in the store windows and then go get you a free colored television. We’re marching for living wages!

Jo Reed: And The Mountaintop is basically a two-hander. It takes place at the Lorraine Motel the night before the assassination and imagines an encounter between Dr. King and a maid named Camae.

Jo Reed: What were the rehearsals like? Because this is a play that demands so much from the two actors on that stage.

Bowman Wright: Oh. What’s great about it was, the first time I did it was with Robert O’Hara. I had did A Raisin in the Sun with him, maybe a year and a half before. So it was one of those things where Robert really trust me, as an actor, so he didn’t want to spend too much time tiring us out in rehearsal. So, basically, our rehearsal schedule was-- it was intense, but it was short. He has this thing, which I love about him, is that if he hires you, he trusts you. But not only does he trust you, he realized, too, too much hammering at something-- you’re not going to let it sink in. It’s not going to sink in enough, where you can just live it. You’ll be thinking about it more than just living it, and then having time to work on it yourself. So, our first time rehearsing, we would spend probably about five hours a day on it. We’d usually spend-- you know, we’d usually spend about eight hours a day. But when you got a two-hander that’s that heavy...

Jo Reed: I was going to say, yeah. There were just two of you …

Bowman Wright: I did it twice, so the second time I did it, I didn’t know the director, and I didn’t know the Camae either, so the-- that’s the other character in the play. And it was their first time doing the play and we literally did spend six to eight hours rehearsing. Now, one wasn’t better than the other. It was just, one took more time, because they needed to figure out stuff, and I needed to figure out how to work with them, and we needed to figure it out. We had a great time. We really had a great show, here in Philadelphia, actually, it was at the People’s Light theatre, and people really responded well to it. We just did it in October, and it closed... maybe November-- something like that.

Jo Reed: Oh, in time for your new baby.

Bowman Wright: Yeah, right in time for my new baby. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Now, let me ask you this, because you’re playing Dr. King in the same play: Is it the same performance?

Bowman Wright: Oh, see, that’s the beauty about acting. And then it’s also the beauty about theatre. Both performances was very different. In fact, this one here in Philadelphia, I think we inspired a lot of people. I mean, and it was so intimate, my Camae was so different from the last Camae, that it brought different things out of me and all of a sudden, I’m working different and I’m thinking different, because I have to think different, because I’m with a different person, and each night is new. But this particular one, I actually felt like I became a better actor because of it. And it was some kind of acting that I’d been trying to do for a long time. It’s amazing, though. You learn more because you can live it more. So, therefore, I’m not thinking about what I was thinking about four or five years ago, when I played Dr. King. Now I’m more settled into him. I’m not going, “Am I good or not?” I don’t make sure that I know the words, making sure that I’m saying the right stuff. I don’t got to do that. All I got to do is just sit in it. And it’s different, and things come out different, and I’m different from um... four five years ago. I’ve grown a lot as a person. So, yes, it’s very different, playing a character twice. I did it with A Raisin in the Sun, too, and I realize how different I was when I played Walter Lee again. And I was like, “Wow, it feels different.” It’s invigorating, because you know, “I don’t have to act. I can just live.” And living is a totally different thing onstage.

Jo Reed: Okay, we’re going to do it one more time, because you played Dr. King in the play All the Way, it’s a play, about L.B.J., but King is such a pivotal character in that play. How did you get into the character of Dr. King in this production?

Bowman Wright: Oh, wow. You know, what was great about that-- and I’m glad you brung that up-- was, what was great was that I had a hell-- excuse my language-- I had a great L.B.J., an amazing L.B.J.

Jo Reed: Jack Willis,

Bowman Wright: Oh, God, the guy was good. We had a great cast. And I had a great guy to play Abernathy. Craig Wallace, he’s just an amazing guy. But it was great, because I got to work with him, and it’s me and him and the guys. We’d get together after rehearsals, we’d be talking, and we’d be learning about things, and learning new things. So it was kind of-- it was getting into Dr. King as an organization, rather than a man just in his… hotel room, dealing with his own thoughts. One of the things I learnt about Dr. King is that most of the time when he did speeches, especially at important times, that he would call 10, 15 friends that he trusted, and he would talk to them about an issue. And he may argue with them or have a discussion about it, but he wanted other thoughts to actually gather an argument before he actually went to go have an argument. <laughs> So it was great, because I kind of did that with the cast that I was with. Even though there’s not a lot of those discussions on the stage, it’s good to be coming onto the stage, thinking, “I’ve been having these conversations. I know what’s going on. So now I need to have this conversation with you. I know what you’re thinking. I know how to talk to you, as Dr. King may talk to you.” And I think, in his play, he-- in All the Way, I think, in some ways, he was telling L.B.J. he had to be the leader. Dr. King is saying to L.B.J.: “Your job as a president, whether you just got it because Kennedy died or not, your job is to be the president. Your job is to make sure that every black person and minority person in America, at that particular time, had the ability and the opportunity to go for the American dream: to get education, to get better jobs and well-paying jobs,” and Dr. King’s job in the play is to make sure that L.B.J. is doing that. And how? Voting rights.

Jo Reed: Now we mention Jack Willis who played L.B.J., he actually originated that part.

Bowman Wright: You know, a great thing about Jack is-- he taught me, too. I learned a lot from Jack, just by watching him. But the great thing I learned from him is, you don’t have to imitate to get people to believe you’re L.B.J., to believe your character. Because he didn’t try to sound like L.B.J. He was always clear about what he was trying to say, as an actor; what the character was trying to say, versus trying to be interesting. He was saying, “I’m going to make sure that the point of what I have to say is clear.” And if you do that, as an actor, you’re actually doing better than acting. <laughs> You’re transcending. You know, if you can get a point clear to people, then people-- they’re not thinking about whether or not you’re good or not; they’re thinking about what you just said, and what you’re doing. And that’s important. And if you’re not doing it for that, then what are you doing it for? <laughs> You know? Other than money, but... <laughs> in theatre, you ain’t making no money, but that’s another thing. <laughs> But... but, I mean, it was great watching Jack, because he said to me that he was saying that, “You are enough. You are enough to do anything. Sometimes your voice might change, sometimes your walk might change, sometimes your speech pattern might change, but it’s all you. It ain’t nobody else. It’s you.” Somebody asked me a couple years ago, how do-- what makes me decide the voice of a character? And actually, I was like, “I don’t even know.” But then I realized something: It was just the way it moved through me. It was me. It was me responding to it.

Jo Reed: Yeah, that’s interesting, because in talking to you it’s not the same voice I heard on the stage when I seen you perform.

Bowman Wright: <laughs> Yeah. I try to tell people, sometimes you start working on a character – I had said to a director, one of my favorites, that, “I’m trying to find the character. I’m trying to find this character.” And he said to me, he said, “What you looking for help for? Let him look for you. He’ll find you. He’ll find you.” And what was great about that, literally, you know when the character’s found you, because you’re not talking no more. It’s like-- it’s almost like you become somebody else. You feel it. It becomes natural. Because I’m not actually sitting there, pushing to do it; I’m just allowing the character to move through me. And the only way you can actually do that is to allow it to be you. And then, at the same time, just go for your action. What do you want? Why do you want it so badly, you know? And what’s the consequences of not getting it? And what can you do? What tactics can you do, the different tactics that you can use, to get what you need? And then do that, and don’t worry about being good. Don’t worry about being interesting. Don’t worry about, you know, whether or not the people in the audience have fallen in love with you. But worry about one thing, is your point getting across, or the ideas getting across. And if that’s getting across, they walk out saying, “Hey, man, I’m thinking about this, I’ve been thinking about that”-- you did a great job. You did an amazing job.

Jo Reed: We touched on this earlier. How do you keep the level of commitment and freshness, night after night after night? To me, that has to be-- for all that’s wonderful about theatre that has to be one of the most difficult things.

Bowman Wright: It is. But I think what makes it easier is your partners. The one thing I’ve always been taught, and I live by, is, get it from the other guy. Because that night-- you know, I’m doing a scene with... you know Joe, I guess, I’m just going to use Joe. And... <laughs> and I’m doing a scene with Joe, and Joe needs something else that night. He don’t need the same thing he needed the night before. I could see that I’m not really getting through to Joe in the same way that I did the night before, so now I have to listen. I’m listening to Joe. That’s the important thing. If I’m listening to Joe, it’s not going to be the same. It’s going to come off different. I’m going to do something different. She going to respond differently. Then, when they respond differently, it’s my job to respond to that, whatever they’re saying to me.

Jo Reed: You really have to be very present all the time.

Bowman Wright: That’s the thing, and that’s the thing about two-handers. Two-handers, you have no choice but to be present every moment. <laughs> It’s not like, you know, you got five people on the stage, and you walk off the stage, and you okay. Ahh – you know, when you in a two-hander, that-- and I think that’s what makes me a better actor is the fact that I’ve done a couple of two-handers. So that actually just helps me realize that even when I’m onstage with five people, now my job is even bigger, because I have to make sure I’m listening to everybody. And then I’m just there. I’m literally living the play, rather than thinking about how good I am, what the audience is thinking. I got to be in the play,

Jo Reed: Well, you’ve done a lot of theatre, and a lot of regional theatre all around the country. How’s-- what’s your sense of theatre throughout the country? Do you find that people are still excited by it?

Bowman Wright: Yes, I think theatre is thriving. Theatre makes people respond – they think differently while they’re there. They actually were thinking. <sighs> That’s why we got to have theatre. That’s why kids got to see theatre. That’s why grown people and people of all nations need to-- sit in the theatre every now and then and watch a play. They’re there. They’re breathing it. They’re with the people onstage, and they’re--it’s funny, I saw Fences on Broadway, and to be honest with you, I know half the people was only there to see Denzel Washington, which is-- you know, hey, I was there to see Denzel Washington, too. I told a couple of friends of mine, I said, “Man, it’s so good.” I looked at Denzel, and at some points, I didn’t even see Denzel. I actually saw my dad.

Jo Reed: Just to piggyback on what you said, it’s this live performance that’s happening on the stage, and you’re there live, but you’re also sharing it with an audience of people. And I think that shared experience is so important and integral to theatre, as well.

Bowman Wright: It becomes a community. It needs people. Theatre needs people and people need theatre. I mean, that’s why theatre is one of the oldest professions in the world. We’re talking about Greek times, where they performed theatre and it was there to talk to the people. It was there to say, “Oh, that’s what the king talking about? Oh, that’s what’s going on in the street?” And people were actually walking around, talking about it afterwards.

Jo Reed: Yeah, or, “That’s what that war was about.”

Bowman Wright: Exactly. So it’s amazing that it keeps going, but it tells you that it’s needed. Art is needed in schools. We need to continue to put art in school. We can’t pull art out of school, because it teaches kids to think outside the box. It teaches kids to be a better person, in a sense that it makes you think outside of you: outside of your situation, outside of your home, outside of your lifestyle. You have to think somebody else lifestyle and yours, and empathize with that. I mean, come on. That’s the best education you can get...

Jo Reed: Tell me what’s next for you, other than your newborn. Which is not an “other than”.

Bowman Wright: No. I mean, right now, it’s the only thing right now. I had an opportunity to do Jitney; the one that went in Cincinnati. And umm-- I backed out of it because I wanted to be home, and make sure I didn’t miss anything with my son

Jo Reed: Being a dad, which is huge.

Bowman Wright: Yeah, and it’s a full-time job. But he’s worth it-- every bit of it.

Jo Reed: What’s his name?

Bowman Wright: Jeremiah Bowman Wright.

Jo Reed: Good name!

Bowman Wright: Hopefully, we do a good job with him, and he come out here, he do something good. Or he just, don’t do bad. <laughs>

Jo Reed: <laughs> I’m sure he’ll do good. Bowman, thank you so much for giving me your time. I really appreciate it.

Bowman Wright: Well, thank you. Thank you for having me, and I really appreciate it.

Jo Reed: That was actor Bowman Wright. You've been listening to Artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the “Art Works” blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

###

Wright on the transformative power of theater and his two portrayals of MLK.