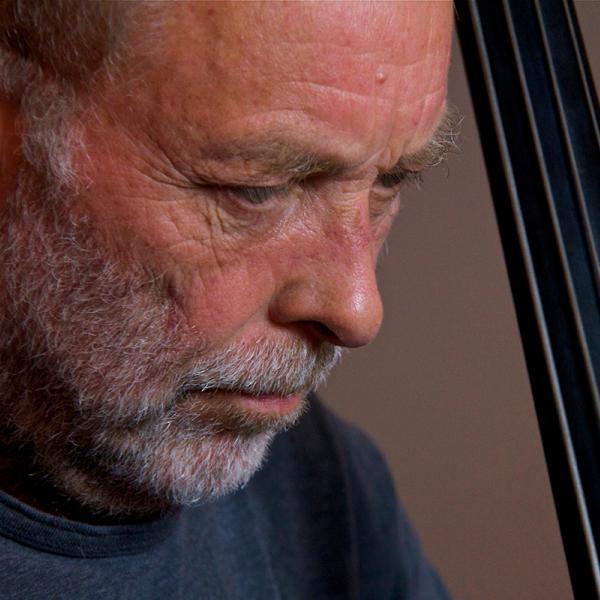

Gary Burton

Music Credits:

“Storm,” composed by Chris Swensen and performed by Gary Burton, from the cd Who Is Gary Burton?

“Sing Sing Sing,” composed by Louis Prima, performed by the Benny Goodman Orchestra, from the album Sing Sing Sing.

“Move,” composed by Denzel Best and Paul Walsh, performed by Hank Garland and Gary Burton from the album Jazz Winds From a New Direction.

“Jive Hoot,” composed by Bob Brookmeyer, performed live in London, 1966 by Stan Getz, Gary Burton, Steve Swallow and Roy Haynes.

“Boston Marathon,” written and performed by Gary Burton from album Good Vibes.

“Crystal Silence” composed by Chick Corea and performed by Chick Corea and Gary Burton from the album, Crystal Silence.

“La Fiesta,” composed by Chick Corea and performed by Chick Corea and Gary Burton from the album, Duet.

“Duet Suite,” composed by Chick Corea and performed by Chick Corea and Gary Burton from the album, Duet.

“Reunion,” composed by Mitchel Forman, performed by Gary Burton and Pat Metheny from the album, Reunion.

Jo Reed: You’re listening to the music of vibraphonist and 2016 NEA Jazz Master Gary Burton. And this is Art Works, the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

Gary Burton is not only a 2016 NEA Jazz Master; he is a musical treasure whose artistry in playing is matched by his generosity as a teacher and mentor. Burton’s four-mallet technique on the vibraphone gave the instrument a new musical vocabulary in jazz. He was one of the creators of jazz fusion in the late 1960s and had a decades-long career at the Berklee College of Music. His range as a musician is remarkable—equally at home with solos, duos, quartets, and chamber orchestras. And he moves with fluidity from country to rock, from tango to classical. But Gary Burton always returning his first best love, jazz. The breadth and depth of his career is even more extraordinary when you realize that Gary Burton was largely a self-taught musician growing up in rural Indiana.

Gary Burton: There wasn't a lot of music available to me. I had started playing the vibraphone and the marimba when I was six. We lived in a larger city at the time. My parents wanted all three of the kids in the family to have the opportunity to take music lessons. And there happened to be a lady that lived nearby who played the marimba and the vibraphone and gave lessons, so that's where they took me. And then we moved to this small town. And in fact, after we moved, I didn't have a teacher, because there were no vibraphone players nearby or anything. And I just was sort of learning on my own. Music was easy for me. I learned already how to read music, and how to manipulate the mallets and play the instrument, so I just kept on going. It was fun.

Jo Reed: Music was about to become a lot more fun for Gary when he listened to a record and discovered jazz.

Gary Burton: I didn't know anything about jazz, at first, but somehow I stumbled across a jazz record.

<Music>

It was by Benny Goodman, and I was captivated by it. It was very exciting rhythmically, and they were doing this thing which we now know as improvisation. They were making up their parts as they played. I was fascinated by that. And so from then on, I was in love with jazz, and I kept trying to find records and copy what I was hearing and see if I could do it.

Jo Reed: The vibraphone was invented in about 1930. So when Gary started playing, the instrument was 20 years old, still fairly new but with a strong first generation of players like Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo, and Milt Jackson. And while Gary looked up to and learned from these players, he found inspiration somewhere else.

Gary Burton: My first big influences turned out to be piano players. In particular, one of the leading innovators of the day was Bill Evans, who had just started putting out his own records in the late '50s, early '60s, and was kind of the new, exciting thing in jazz. And so I listened to him play, and I said, "If he can do that on piano and make it so musical, then surely I can do something similar on vibraphone."

Jo Reed: And the influence of the piano was certainly a factor in Gary’s unique style of playing.

Gary Burton: It also encouraged me to start playing the vibraphone with four mallets instead of two, which was the style of the day—playing two mallets. I played alone a lot because of where we lived, and it sounded too empty. I needed harmony; I wanted it to sound complete. So I started with slow pieces where I could manipulate the four sticks, even though it was fairly clumsy at first. But as I got more dexterity with it, I could play faster songs as well. It became my way of playing the vibraphone. I didn't know that no one else was really doing this at the time until I got to Boston, frankly, and everybody said, "No, nobody plays that way. You should only play with two." But I had found my own way. And I was too far into it to change styles.

<Music>

Jo Reed: Luckily Gary wasn’t stuck in isolation. He found some people to jam with in Evansville, about an hour away from the family home.

Gary Burton: I started finding older, local musicians who were not major jazz players by any means, but they already had been playing jazz for years and a piano player, a bass player and so on. Pretty soon I proved good enough to get invited to be on some of their gigs. I played in local clubs and local at parties and events and so on. This would be, now, in high school but particularly the last two years of high school.

Jo Reed: Still, Gary wasn’t thinking about a career in music, let alone one in jazz. But that was about to change.

Gary Burton: I was a straight-A, honors society student. I had kind of settled on going to medical school. And I went to the first ever jazz band camp which happened to be taking place at Indiana University, a few hours' drive from where I lived. It was so great that when I came back home, I went to my parents and said, "I've changed my mind. I'm going to try to be a jazz musician." To their credit, they didn't blink; they were supportive. And when I look back on it, I'm amazed. I mean what parent wouldn't at least put up a fight? My goal was to go to school for jazz and graduate and move to New York. And if I was lucky, I might get to be on a record someday.

Jo Reed: That day came sooner than Gary Burton expected.

Gary Burton: There was a guitar player in the country music scene named Hank Garland in Nashville, Tennessee. He also had fallen in love with jazz and had become quite a good jazz player. And he convinced his record label to let him make a jazz record instead of a country record and wanted to team up with a vibraphone player. He liked this idea of the sound of vibes and guitar. But there were no vibraphone players in Nashville.

Jo Reed: But Garland knew a musician from Indiana who knew Gary, and Burton found himself auditioning for Hank Garland. It went well.

Gary Burton: And he asked me what were my plans and I said, "Well I'm finishing high school in another month and then in the fall, I'm going to Boston to go to college." So he suggested that I move to Nashville for the summer, and we would play in a local club on weekends, and we'd make this record which sounded amazing to me. So that's what I did. I packed up and drove to Nashville and we made the record.

<Music>

And at the end of the summer, one of the fans of our little trio when we played at the club was a guy named Chet Atkins, a famous country guitar player. And also he headed up RCA Victor's record division in Nashville. He came to me and said, "We should sign you to a contract." I was 17, and I left for school, Berklee College of Music, with a record contract in my pocket. So that was quite a summer.

Jo Reed: It’s telling that despite the experience of performing and a record contract in hand, 17-year-old Gary Burton was still determined to go to music school.

Gary Burton: I had figured out a lot of music by ear and experimentation, but I didn't know how it was really organized. I didn't know what to call things. I knew this chord sounded good, and that one sounded good here. And this one led to that one, but I didn't know why. So I needed information. I felt like I needed to go to school. That turned out to be a wonderful experience. The school was great. It was tiny, but great teachers, great fellow students, and a very active music scene around Boston; that was just as important as the school. Then I ended up having a relationship with Berklee for the rest of my career as a teacher, administrator, and so on as well.

Jo Reed: People often think of New York as the epicenter of the jazz world, but Gary discovered Boston had a lot to offer an eager young musician.

Gary Burton: The jazz community in Boston, in some ways, had many advantages over even being in New York. Because of Berklee, there was a student and teacher community in Boston. And the teachers were the best local musicians in town, and they played regularly, so you could go hear your teachers play. If you were actually good enough, you could even get on gigs with them. And I played a lot of dates with some of my teachers. So the scene was very accessible to young musicians in Boston.

Jo Reed: But after college, New York City and its jazz scene called, and Gary Burton answered.

Gary Burton: Lucky for me, I got a job fairly soon after moving to New York thanks to a wonderful person and musician named Marian McPartland.

Jo Reed: Marian McPartland was so taken with Gary’s playing, she called her good friend, the pianist George Shearing, who happened to use the vibraphone in his band.

Gary Burton: I had been in New York maybe a month, and I got a call to come and audition for Shearing. And that got me my first full-time touring-around-the-world. I toured with George for a year. I was 19. And then he decided to stop touring for a while, and suddenly I was out of work and back in New York wondering what to do next. And I went on unemployment. I got two checks, and then I got hired by Stan Getz. And that was my next band, and I toured with Stan for three years.

<Music>

Jo Reed: Gary joined Stan Getz in the mid-1960s, a time of great change both socially and musically.

Gary Burton: Jazz had a big challenge when, what I call, modern rock music arrived. In the mid-'60s, here came the Beatles, and Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones—more sophisticated rock, more sophisticated recordings. A typical Beatles record included a string quartet on one track, some Indian sitars on another. Different kinds of music, different styles of music, different recording techniques—this caught the ear and the attention of a lot of people in the jazz world, because here was something that we could actually appreciate. And it was hard to ignore, particularly if you were my age, 25 years old. I became a huge Beatles fan, and it gave me a sense of where I wanted to go with my own band when I left Stan's, pretty much, traditional jazz band to start my own. Part of it was just what I was excited about musically, and part of it was cold calculation. I looked at the audiences we were playing for and noticed that I was 25, and they were 40 and 50. And I figured it out, and I said, "Well, by the time I'm 40, they're going to be 80, and they're not going to be coming to see me play." So I needed to find a younger audience, my age. So I had the idea to somehow combine rock and jazz. That was my first band, and the music press started calling the music, fusion jazz.

Jo Reed: The sound was pure gold.

<Music>

Gary Burton: I was thrilled that the public and the jazz fans accepted what we were doing. If we had failed, it would have been an epic failure. I would have looked ridiculous. “Who thought you could do this?” There was a certain backlash from jazz musicians. You know, rock was the traitor; it was taking away our audience. There was a real sense that we were in danger of being overwhelmed by the rock scene.

Jo Reed: But as much as Gary appreciated rock, jazz had pull that was irresistible.

Gary Burton: Jazz has one unique factor: it's based on improvisation. Other musics have some degree of improvisation. But jazz music, this is where the spotlight is. The degree of sophistication of improvisation in jazz music is pretty unique to jazz. And that is a real siren call to many musicians. If you have a knack for it and really love the process of how improvisation works, it's really hard to give it up. No other music seems quite as exciting. You become an on-the-spot composer, as well as performer. So there's a lot more room for personal expression.

<Music>

By ’69, ’70, I had arrived. I was no longer a new thing just starting out. I was now established. And I was able to be more selective about what gigs I would take. I could count on the players I wanted. I was feeling quite positive at that point in my career, just looking forward to seeing, “Well, where is this going to take me musically?”

Jo Reed: It took Gary Burton to the collaboration of a lifetime.

<Music>

Gary Burton: I've been lucky to have a few collaborations in my career that have lasted for years and years. And a lot of great music has come out of each of them. Certainly, the most significant has been with Chick Corea.

<Music>

We sort of knew each other, and we ended up in 1972 in Munich at a jazz festival. There were five different musicians who were on this concert, and the concept was that each of us would play a solo segment. But the organizer then got the idea that he'd need some kind of finale, some kind of finish. "Can you all jam a tune together or something?" And it turned out that only two of us had said yes, me and Chick. We came out and we played this piece, "La Fiesta," now one of his well-known pieces.

<Music>

The audience went crazy. They loved it.

Jo Reed: There happened to be record company executive in the audience that night who was convinced Gary and Chick should cut a record as a duo.

Gary Burton: We thought, “Oh, come on. Who wants to hear a whole hour of just piano and vibes? Come on.”

Jo Reed: But the rep was persistent and some months later, Chick and Gary found themselves in a Berlin recording studio ready to cut their first record together.

Gary Burton: We had put aside three days, because we weren't used to playing together. We thought, "Well, we'll have to work up what tunes to play, and rehearse them, and so on." But, it ended up, we did the whole thing in about three hours. Everything was a first take except for one song we did twice. We sat around listening to the tapes for a while and said, "Well, we're done." So we changed our plane tickets and flew home. And the record came out on this very small German label. It didn't even have a distributor in the US at the time; you had to order it by mail. We didn't think much would happen. It'd be something that would slip under the radar. Our agent got a call wanting to book a concert for us at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. So we went to the college, to the concert hall, and walked in, and it was huge—4000 seats. I thought, "Oh my gosh, this is going to be dreadful. We're going to have like 200 people scattered out there in this huge place and the two of us up on stage trying to play." It came time to play, and I looked around the curtain at the audience and was stunned; it was full. And then I was panicked about how we would handle that, because there were only two of us on this big stage. So we went out and we played; it was a big success. And we just kept getting more requests for concerts. By that time, I realized that there was something definitely going on with this new duet that we had. And it's turned into a major part of both of our careers.

<Music>

Over 44 years now that we've been playing together. We play every year. And we do a little tour, make a new record, or something. We've won six Grammy’s playing together on different collaborations of our duet records.

Jo Reed: So why is it that some musicians click and play together as though they born to it?

Gary Burton: The musical connection that I have with Chick Corea is something that's unique in my history. You have some degree of rapport with any musician you play with. On a scale of one to 10, with some players, it might be two or three, "Ok, we can play together." With somebody else, it might be six or eight. "Yeah, we really can feel a lot between us going on." With Chick, it was 10, almost from the beginning. Improvisation is like, in a way, like having a conversation with someone with one big difference. When you talk back and forth with a friend who you know well, and you can even jump ahead. You can guess where they're going to go next, because you know them so well. But when you're playing music, you talk at the same time. You're playing at the same time. But you're having, nonetheless, this conversational interaction.

<Music>

It's just a unique thing that the two of us happened to find each other.

Jo Reed: Gary Burton is also a groundbreaker in jazz with his decision to be open about his sexual identity.

Gary Burton: There have been very few openly gay musicians in jazz. I was certainly one of the first. There are others. There have been others. But it's a rarity compared to – even pop music seems to have more opening gay musicians and performers than jazz does. That was just, in a way, the nature of the music. For me, the music itself was so powerful and attraction that I had no doubt that this was what I wanted to do. And whatever it took, I was going to go for it and see my way into it.

Jo Reed: Gary Burton also took on a whole separate career as a teacher, then dean, and finally vice president at the Berklee College of Music. He worked this second job for 33 years, retiring in 2004.

Gary Burton: I started doing clinics or master classes. I found that talking about the music and being in the role of the teacher was pretty natural for me. So I called Berklee, my alma mater, and said, "What do you think about me moving to Boston and teaching?" So they thought that was a great idea. The idea was to teach and continue touring during the vacations, and weekends, and so on. And I almost killed myself the first couple of years fitting so much stuff in. I didn't want the jazz world to think I had dropped out, so I filled every weekend and filled every vacation period. But I was really enjoying it and getting a lot of ideas about music from the experience of working with the students. There's so much excitement that comes watching young players that can't wait to get to the gig each night. Every night is a new thrill, and it rubs off on us old-timers when we're around that. I call it the unpredictability of youth. It's one of the great sources of energy and inspiration that I have found in my career.

Jo Reed: Jazz has a rich history of mentorship. It makes sense because for decades, you couldn’t study jazz in a school; you had to learn on the bandstand.

Gary Burton: I learned about mentoring, I think, from Stan Getz, who had a history of hiring young players to play in his bands. He hired me when I was 21 years old. He hired Chick Corea as a young player, and many others through the years. While Stan himself wasn't really very verbal about musical things, he was a great role model, musically, with his playing. I felt like a learned about the business, as well as about the music, from Stan. It was a natural thing for me, then, to continue on with this same kind of approach to being a band leader. And it tied in with my teaching, as well. Soon I was teaching students, and in some cases, hiring them when they graduated to be in my bands. Sometimes they found me, and that was the case with Pat Metheny.

<Music>

Jo Reed: It turns out Pet Metheny was a great Gary Burton fan. The two met when Gary played a festival in Pat’s Kansas hometown. Metheny in college at the time in Miami, and he hopped a bus, and showed up in Kansas ready to play.

Gary Burton: He sounded really good, very promising for a student, and I could see the talent was really strong. His last question was what should he do. I said, "Leave Miami [laughs]. Go somewhere where there's a very active jazz scene—where there's a lot of other players—either New York or Boston.” And he showed up in Boston a few months later, and he started just playing locally. And within a year, he was joining my band. We ended up playing for three or four years together as he developed into the Pat Metheny who went on to form his own bands, and his own records, and so on.

<Music>

But this seems to be my history. I find young players and not always, but sometimes, I can just extrapolate where they're going to be 10 years from now. I can hear it in what they're playing. And I want to share in it and play with them. It's always inspiring to come across a young player who's discovering their talent and to see it develop and helped. Sometimes, I think, they don't even need me. They would get there anyway. But I flatter myself to think that I played a part.

Jo Reed: There is no doubt that Gary Burton has played a big part in the careers of many musicians. And he’s played a big part in expanding and enriching the music, itself. But Gary also believes deeply in legacy and the importance of keeping that legacy alive.

Gary Burton: Jazz musicians from my generation are in a very unique position. I was lucky enough when I was starting out to meet, and get to know, and even play with some of the giants of jazz—the people who created this music almost out of whole cloth. Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Stan Getz, Lionel Hampton – I knew these musicians, played with some of them, were given advice by them, were friends with them. And now, my generation is the bridge to the young musicians of today who we're their last connection to the beginning of jazz. We were there, so we can tell them stories about the musicians, and we can share our experiences with it. We have a big responsibility, frankly, to pass on our experience to the next generation who are going to be carrying this great music into the future.

<Music>

Jo Reed: That was 2016 NEA Jazz Master and vibraphonist Gary Burton. You've been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

One of the great jazz virtuosos take us through his musical journey.