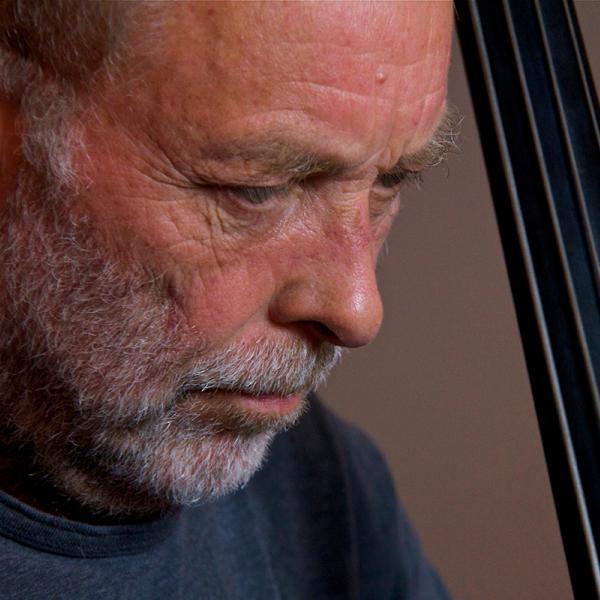

John Hickenlooper

Transcript of conversation with John Hickenlooper

Mayor John Hickenlooper: The kinds of activities that lend themselves to historic neighborhoods and historic preservation, are also the kinds of activities that are connected in some way with culture, that you often see. It’s almost like a evolution where you’ll go into an older, abandoned part of a city. In New York, you’ve seen generation after generation of this, but you also see it in Chicago. You see in San Francisco. You see it in Denver where an abandoned part of the town-- first, the art galleries go in and they’re almost like the pioneers. And then once they establish a beachhead, then sometimes you’ll find some lofts, some people that want to live in a place that’s a little more urban. They’ll come in, and then you get certain other businesses, usually restaurants, are kind of a close follower to the galleries. There’s a progression of different businesses that move in and, over a period of time, transform this abandoned part of the city into this new, hip area. And that’s urban revitalization.

Jo Reed: That was Mayor John Hickenlooper talking the arts-driven revitalization of downtown Denver. Welcome to Art Works, the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation’s great artists to explore how art works. I’m your host, Josephine Reed.

Mayor of Denver since 2003, Hickenlooper is an unstinting supportor of the arts…eager to demonstrate that it’s culture that makes a city vibrant.

“culture first, commerce follows” is his oft-quoted mantra and he knows this from the business side. He was a successful entrepreneur who established the first brewpub in the Rocky Mountains which eventually grew to seven restaurants in the Denver area. In the process of building his restaurants, he became involved with numerous downtown Denver renovation and development projects and is credited as one of the pioneers that helped revitalize Denver’s Lower Downtown historic district.

Jo Reed: Mayor, I want to begin by asking you about the Mayor’s Institute for City Design. You took part in that.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Yes, very shortly after I was elected, I had a wonderful experience. We did it in Charleston. Mayor Riley [ph?], who’s been mayor now-- is it 33 or 34 years-- certainly the dean of all mayors everywhere. And for two days, we just thought about the issues of design and how they affect urban areas. And some of the restraints, some of the ways to think about it, it was one of the most beneficial experiences of my first year in office by far.

Jo Reed: Well, can you tell me what actually happened there?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, they invite several different mayors. I think they had four mayors there. And they ask you to bring a really challenging issue that exemplifies the aspects of design that can affect a large urban project. So we brought the-- we’re taking our old Union Station and transforming it into a multi-modal transportation hub with commercial and retail and housing and light rail and commuter rail and regional buses. So how that all comes together, what it’s supposed to look like and how it relates to the old historic neighborhood where my old restaurant was, became a big issue. And so I came and the three other mayors all had similar big, meaty issues. And then I think they had five national experts in design-- architects, planners, people that have spent their lives thinking about design-- and we would spend about two and a half hours on each issue over the course of two days. So I got two and a half hours about my issue, but I also got to spend two and a half hours about, I think it was three other issues, with these experts and the mayors. Sometimes, I felt like I learned more discussing something to do with Omaha than I did really even my own issue in Denver. It was a fascinating process.

Jo Reed: Well, Mayor, before you even entered politics, preservation, design was very, very important to you. You got a National Preservation Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1997 when I don’t even think running for mayor was a gleam in your eye.

Mayor Hickenlooper: <laughs> It’s true.

Jo Reed: Why, as a businessman, did you think it was important?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, I saw a lot of benefits to connecting business and culture and art. When we first opened my first restaurant, the Wynkoop Brewing Company, back in 1988, the rent in our historic district, Lower Downtown, was a dollar a square foot per year. I mean, it was an abandoned warehouse district, and yet it had this wonderful human scale and it was safe. It was abandoned but it was safe and clean. And one of ways that we kind of rejuvenated that whole area was art galleries. One of the reasons our restaurant worked so well was we got- actually had a halftime curator who had relationships with all the different galleries, so we had rotating big works of art on this- on the walls of this old warehouse that we turned into a restaurant, brewery. And you know, I just became really kind of invested. First, we did the one in Denver; then we did one in Fort Collins to the north and Colorado Springs to the south. And we did one in Omaha and Des Moines and in Green Bay, Wisconsin, always historic buildings, always downtowns, and always trying to take this brew pub, this restaurant as a way of rejuvenating the downtown area. And you know, the design and bringing art into the building became a big part of that kind of- the continuity of that business plan.

Jo Reed: And did you find that, as you moved to these downtowns that you were trying to revitalize, that other businesses, other art galleries would follow that, that art, in fact, promoted the economic development of those areas?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Absolutely, and especially in historic districts. <clears throat> Excuse me. There’s a real kind of overlay of the kinds of activities that lend themselves to historic neighborhoods and historic preservation, are also the kinds of activities that are connected in some way with culture, that you often see. It’s almost like a evolution where you’ll go into an older, abandoned part of a city. In New York, you’ve seen generation after generation of this, but you also see it in Chicago. You see in San Francisco. You see it in Denver where an abandoned part of the town-- first, the art galleries go in and they’re almost like the pioneers. And then once they establish a beachhead, then sometimes you’ll find some lofts, some people that want to live in a place that’s a little more urban. They’ll come in, and then you get certain other businesses, usually restaurants, are kind of a close follower to the galleries. There’s a progression of different businesses that move in and, over a period of time, transform this abandoned part of the city into this new, hip area. And that’s urban revitalization.

Jo Reed: I know from your thinking, you tend not to think in silos, so that’s there’s urban revitalization here, A; and then B, is sustainability. You tend to look at a model that encompasses both.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Absolutely. And that was one of the real attractions to doing these historic districts in downtowns, because-- and I remember vividly when I- as I was walking through Lower Downtown-- it’s about- it’s a fairly large area. I think it’s roughly 40 or 45 blocks of historic, turn-of-the-century warehouse buildings in downtown Denver, kind of on the west part of the downtown edge. And as I walked through it, I said, “God, the buildings are at a human scale. It’s clean; it’s safe. It’s been abandoned but I would want to live in here. I mean, I think this would be a great place to live.” And that was part of the premise. As we did the restaurant, we eventually- after about two years of a successful restaurant, we did lofts on the upper three floors of this beautiful old 1899 warehouse. And soon, other entrepreneurs, other developers were doing similar projects around us. And sure enough, there were a lot of people, either empty nesters or young kids just out of college-- those were the kind of two different components of the population that was looking for this more urban experience. But the sustainability aspect is, as people are living downtown and walking to work, you avoid a lot of the real problems with economic growth, right, the congestion, the traffic, the air pollution from burning all that energy. You know, when you’re living in urban areas, usually you’re in a condominium or an apartment building in a multi-floor, you know, a five-, ten-story building. Well, by having the buildings one over top of each other, much more energy efficient, you don’t need as much water for- you don’t have grass in your yard. You don’t have- your roofs. Roofs of homes are always where the maximum heat is lost in the winter, the maximum air conditioning is lost in the summer. In an apartment building, you’re just much more energy efficient. So having that downtown emphasis made us more energy efficient in so many different ways, and water conservation went up. I mean, it just became much more sustainable.

Jo Reed: Denver is also graced with having .1 percent sales tax put aside for art.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, and that is one of those things. I think we’re the only large metropolitan area-- called the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District. And it takes one-tenth of 1 percent of the whole metro area, so it generates about a little more than $40 million a year now, even after the recession. And it allows our large cultural institutions to really have a reliable level of public support. So the-- I mean, it’s one of the reasons why our Museum of Nature and Science-- you know, Denver is roughly the 18th or 19th largest metropolitan area in the United States, but we have the fourth most visited museum, Nature and Science; the fourth most visited zoo in the United States. I don’t know where the art museum is but it’s very high. We have the second largest performing arts center in our downtown, second only to the Lincoln Center. All those incredibly valuable institutions to our quality of life, to how we go about things wouldn’t be possible without the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District is the fact. It also allows us, since the distribution of the revenues that are collected through the SCFD are based upon paid admissions that allows us to measure how much attendance and how much money is really being generated by our cultural community, which again becomes a very valuable tool for nonprofits like the symphony or the opera or the art museum or the Museum of Nature of Science. It allows them to be much more persuasive in going after philanthropists or corporate contributions, say, “Well, look. This is where the part of it is for our economy.” You know, the SCFD funds over 300 different museums, theaters, various types of cultural and scientific institutions over the whole metro area. So we collect all this information and we can say, “The direct economic impact of our cultural community is north of 1.7 billion dollars a year.” And you know, we get Coopers and Lybrand or one of the big accounting firms to do this for us. It really becomes another arrow in the quiver when you’re trying to drive economic development.

Jo Reed: So I just want to make sure that I’m getting this right, that approximately, and I understand we’re speaking in approximates here, that $40 million of investment generates over a billion dollars.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Exactly. I mean, it is a dramatic-- I mean, we would have a significant part of that 1.7 billion already. But I’m a big believer that the future economic generators are not going to be so much incentives that state or local governments offer to businesses, but really, reflective of quality of life issues, so that the same kinds of things that would attract a convention or a tourist to come visit Colorado-- right, the 300 days of sunshine or the Colorado Rockies, all these things that we trumpet all the time; 850 miles of bike paths in metropolitan Denver. They also become part of our economic development effort to attract businesses to open an office here or move here. And our cultural investment becomes a huge part of that. I mean, I’m-- you know, we just had a Fortune 500 company called DaVita-- they’re the world’s largest dialysis company, and they’re, I think, number 440 or 430 on the Fortune 500. And they were consolidating. They had offices- you know, executives all over the country, and they chose Denver, largely I think, because we do have the fourth most visited Museum of Nature and Science. We do have the second largest performing arts center. They looked at our investments in our cultural community and said, “Huh, we might be able to attract more talented workers because of what a great place to live this is and be more competitive and keep them for a longer time by having our headquarters in Denver.

Jo Reed: And that one-tenth of 1 percent also funds a lot of public art, which I assume adds to the vitality of the community.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Absolutely. I mean, we-- again, you build momentum around these things. And at least in the city and county endeavor, we have a 1 percent- every municipal construction project. So if we’re building a bridge or a public building, we’ll take 1 percent of the total construction cost and use it for public art. And that just again creates that increasing critical mass.

Jo Reed: I want to talk about some of the wonderful museums that are in Denver, if we could, please.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Absolutely.

Jo Reed: The Denver Art Museum, the Hamilton Building, that was quite an opening you had.

Mayor Hickenlooper: <laughs>

Jo Reed: It is a very unusual building.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, if you look at it, it almost looks like a mineral crystal. Right? Something you’d find in a mine deep in the earth, but almost looks like a mineral crystal sprouting out of the ground with these, you know, sharply slanting walls and prismatic shapes. But I love it. I mean, I think, you know, why have we revolutionized what art can be and what art is to us, and yet we still insist on looking at all sculpture and all painting in rectilinear, you know, right-angle, white gallery spaces?

Jo Reed: And that building-- well, it did generate a lot of conversation.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Yeah. <laughs> Well, people either loved it or hated it, although I think people are generally coming and being more accepting, giving it the benefit of the doubt. And as they do that, it-- actually, it depends on the exhibit, and there are a number of galleries in the new Frederick Hamilton Wing of the Denver Art Museum that is-- they are square and rectilinear, that there are enough of these funny shapes that really- you know, you can show all different kinds of art in an appropriate space. And it certainly has become- the shape of the building has been an icon. It helps define the city in much the same way that the kind of tinted roof of our airport defines the city.

Jo Reed: Will people talk about the Bilbau effect with Frank Gehry’s building of the Guggenheim in Bilbau and the same kind of striking building that, in some ways, put Bilbau on the map for art lovers?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Absolutely. I think-- yep, absolutely. And that was part of the goal. I’m not sure we got the same impact that Bilbau got, just because what Guggenheim did was the first time, to my knowledge, that a museum of that size and that stature had invested in such a dramatic and revolutionary form. The shape was just so dramatic that suddenly it was the first time a museum said, “All right. We’re going to make the actual museum part of the cultural experience when you go to see art within it.” And by being first, I mean they got millions of people-- again, the Frederick Hamilton Building has been similar in that sense that it has dramatically increased people coming to see art in the museum. I think it’s dramatically increased people coming to Denver to see art, but not quite the same. I mean, Bilbau, I don’t think there will ever be another building that hits the world so dramatically as Bilbau did.

Jo Reed: You also played a key role in the museum that’s under construction now, the Clyfford Still Museum.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Yes. We hope to open it in about a year, year and a half, I think. And Clyfford Still, obviously, was by most measurements, most experts, one of- if not the primary, but one of the first real creators of abstract expressionism. And yet, he rebelled against the commercial aspects of Jackson Pollock and some of the other expressionists, you know, how they would compete to sell their work and how much they could sell it for. And he only sold 75 paintings in his life, 75 or maybe it was 80 paintings. He left this collection of almost 2,500 pieces of art, more than 800 major canvases, all left to his wife with a very expressed will that said it could only be left to a city, not to a museum, but to a city that was willing to create a museum, and the museum would strictly be about Clyfford Still. And obviously a very bold and he was not lacking in confidence, but he was revolutionary in how he approached art. And now, as we’ve gotten to see a number of his paintings, they are breathtaking, and he changed- he was one of the people that really changed the direction of art. And whereas most of the abstract expressionists, you can go to a museum and see two or three or maybe four of their works, maybe six or seven. There are very, very few places, very few museums dedicated to a single artist where a huge portion of their work, in this case 90 percent of their entire creative output will be available in one spot.

Jo Reed: And you were instrumental in making that happen before you were mayor.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, I was part-- <laughs> it was early when I was in, and Louis Sharp [ph?], who was the- just stepped down and retired as the director of the Denver Museum of Art and is just a true visionary, he had mentioned this. The widow of Clyfford Still, Patricia, her nephew lived in Denver and was actually a brain surgeon. And he had mentioned to Louis, and Louis and he had made- had some discussions a few years before. But Louis convinced me. We all flew out to Maryland together about 70 miles west of Baltimore and visited Mrs. Still in this beautiful in old farmhouse, and there were literally hundreds of canvases rolled all over the first floor that she’d just been keeping there. I mean, just for a frame of reference, I mean, his paintings have sold for close to $20 million for an individual canvas. I mean, he is one of the most collected and valued of the early abstract expressionists. And here are all these, you know, literally hundreds of canvases sitting there unguarded. <laughs> It was a pretty amazing experience, and his widow was very charming and very eloquent. And it was a long discussion. She was also very eccentric and very cautious, but we finally reached agreement on what the museum would look like and how we could build a museum in Denver, raise- you know, raise the money philanthropically and go forward.

Jo Reed: Art also happens, as we spoke about briefly, on the grass roots level. There are Friday, first Friday art walks, are there not?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Yes, we have a number of kind of emerging neighborhoods that have a number of galleries in each neighborhood. And so there are first Friday art walks the first Friday of the month. There are a couple first Thursdays. But the notion again, this is all part of the momentum around your cultural communities, part of what the SCFD helps create. And I did mistake it. It is- Deloitte is the accounting firm that donates their time to do the actual measurement of the economic impact, based on all the numbers that come in from the SCFD. I can’t believe I didn’t say Deloitte. I should be shot.

Jo Reed: <laughs> I’m sure they would agree, but I don’t.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Exactly. But that effort of getting more people involved in recognizing the value that art can add-- I mean, there are a number of studies. I’d love to make Denver a place where we got-- I’d love to get our businesses to commit to spending one-tenth of 1 percent of their payroll every year to buying art locally so that we become kind of a Mecca for young, talented artists; you know, that they knew there’d be a market here. And there are all kinds of studies that the Colorado Business Committee for the Arts-- and they’re the ones who worked with Deloitte in terms of getting this study done on the economic impact. They did a study at Storage Technology about 10 years ago and actually measured the impact, and it was dramatic, of how many businesses in a competitive environment where different companies are trying to lure your employees-- how many of your employees, not businesses, but how many of your employees would be less likely to take another job because of the art on the walls? How many of the employees feel that that art helps them solve difficult intellectual problems? And the solving intellectual problems was almost 50 percent. People that felt that it would make it harder for them to leave the company because of this great art on the place was north of 60 percent. It really demonstrated that for a relatively small investment, one-tenth of 1 percent of a company’s budget, they could have- be much more competitive in retaining their employees and having their employees be more productive and successful in their jobs.

Jo Reed: Well, I think this leads very nicely into Denver’s Biennial of the Americas, which is going to start in a week, I believe.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, actually, we’re going to have the kickoff- the gala celebration is tonight and it’s going to...

Jo Reed: Oh, sorry.

Mayor Hickenlooper: That’s okay. It really gets into speed next week. You’ve got the right facts, but as a mayor, I have to make sure I celebrate every moment of the Biennial. But, yes, this will be the first, the inaugural Biennial of the Americas. We hope to do this every two years, but it’s a- you know, it’s almost like a world’s fair of ideas and innovation and culture. And instead of so many-- so often, the United States looks towards Europe for our cultural touchstones. We look towards China or maybe India, towards Asia in terms of our future economic development. And yet, we have this incredible hemisphere that we’re part of where we import more oil from our hemisphere than we do from the Middle East. We’d have more trade within our hemisphere than we do with China, and it’s growing at a faster rate. We have these incredible countries that we almost- Americans aren’t paying attention. Brazil is soon going to be the fifth largest economy in the world. So the Biennial, the goal here is to bring-- we’ll have people from 35 different countries, performing artists. We have a wonderful exhibit in a beautiful old building in our Civic Center Park, the old McNichols Building-- it’s originally a Carnegie Library-- that we’ve converted into this public space. And there are artists from 24 different countries that are-- it’s an exhibit called The Nature of Things. And it kind of collects this idea of, what is this hemisphere about? And what are some of the common threads? What is the DNA of the Americas? It’s very excited- it’s very exciting.

Jo Reed: And you’re going to do this every other year from now on. This is the inaugural biennial.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Exactly. And so I’m sure it’ll change and we’ll have different curators. Paola Santoscoy, who’s from Mexico, has been the curator this time and he’s done a remarkable job. But a different curator will have a different tone. We have all of our local institutions, like the Museum of Nature and Science, the Art Museum. The Botanic Gardens has a bunch of- has a wonderful display of orchids, but all these institutions are connecting to the Americas in different ways to try and create a critical mass and really for the next four weeks, for the month of July, to immerse the entire metro Denver region in the Americas. It’s almost like a hemis-fair, as opposed to a hemisphere. <laughter> If you’ll pardon that awful pun.

Jo Reed: I will. But just speak briefly, if you don’t mind, about how art and cultural exchanges really are crucial for all aspects of international relations.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, we looked at it as equal parts cultural exchange and business exchange. The people that support culture in Argentina or Brazil are the same people that support it here. They’re generally well educated. They’re well traveled. Oftentimes, they manage or own large businesses or other enterprises. The people that really support culture are often very, very enmeshed in the business community. And I think one of the best bridges we can make towards more exports, a stronger economy, is to use culture as that bridge. It’s strong. It allows people to look at a different country in a whole new perspective and appreciate what that country is doing, and in that process, I think, of building that bridge, you create an opportunity that soon you’re going to have commerce and trade. And that’s one of the most historic and reliable ways of creating wealth that we’ve ever known, right, is trade generally benefits both sides.

Jo Reed: Let me ask you finally, we all know these are not the best of times economically. And many people feel during times like that, that’s when you can put art on the back burner; there just isn’t money for it, and that they’ll come back to art when times are better. What do you say to those people?

Mayor Hickenlooper: Well, I mean, obviously in city government and state government, we have had to tighten up dramatically over-- it’s just not this year; it’s been over the last, really, six or seven years. Since I’ve been mayor, the city government in Denver is now five and a half percent fewer people than when I started seven years ago. And that kind of belt tightening is happening everywhere and even in our cultural funding in terms of our public investment. But we- this country still has a huge, huge component of remarkably successful entrepreneurs and executives, and they are, I think, recognizing that even in a down economy, sometimes that’s the most important time to make investments in our cultural community. And even when a symphony or a ballet or an art museum are struggling to balance their budgets, that’s when people really have to step forward and find more creative ways of raising money, better ways of generating public support and getting higher attendance. I mean, oftentimes as difficult as recessions are, they do-- when I started the Wynkoop Brewing Company way back in 1988, it was one of the worst recessions that Denver had had since the Great Depression, not quite as bad as today but very, very close. And yet, there was opportunity there for people willing to make that investment. And of those kinds of investments, I think culture should always be a significant part of it.

Jo Reed: Mayor Hickenlooper, thank you so much. I really appreciate your time.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Josephine, it was my pleasure. Thank you so much for taking your time.

Jo Reed: No, it was my pleasure too, and say hi to Helen for me.

Mayor Hickenlooper: I will definitely do that. Thank you very much.

Jo Reed: Okay, thank you. Thank you, Daryl. I appreciate it. Adam, thank you.

Mayor Hickenlooper: Thank you all. Have a great day.

Jo Reed: Thanks. You too.

That was Mayor John Hickenlooper talking about how art works in Denver. You’ve been listening to art works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the assistant producer.

The music is “Renewal” by Doug and Judy Smith.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday. Next week, tenor and director of opera at the University of Kentucky, Everett McCorvey.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

John Hickenlooper discusses his efforts to use the arts to revitalize Denver and promote economic development and increased livability. [23:37]