When the Emperor Was Divine

Overview

A day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Julie Otsuka’s grandfather was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on suspicion of being a Japanese spy. Her mother, grandmother, and uncle were subsequently interned at a camp in Topaz, Utah. Otsuka draws on both research and personal experience, as well as her background as a visual artist, to craft this crystalline, semi-autobiographical debut novel, winner of the American Library Association's Alex Award and the Asian American Literary Award. The internment experience in the novel is recounted through the varying perspectives of a mother, father, daughter, and son as they survive in the camp and then return home after two years to their old neighborhood that is neither familiar nor hospitable. This is “a gem of a book and one of the most vivid history lessons you’ll ever learn” (USA Today).

"Mostly though, they waited. For the mail. For the news. For the bells. For breakfast and lunch and dinner. For one day to be over and the next day to begin." —When the Emperor Was Divine

Introduction

It all began with a sign. Posted on telephone poles, park benches, community centers, and a Woolworth's, Executive Order No. 9066—issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt—sought to prevent “espionage and sabotage” by citizens of Japanese descent in the wake of the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. Japanese Americans were arrested, rounded up, and transported to detention centers across the United States, where in some cases they were held for several years.

This sign, introduced in the first line of Otsuka's novel When the Emperor Was Divine, prompts “the woman” to begin packing important belongings. After her children return from school and work quietly on their homework, the woman tells them that tomorrow they “will be going on a trip.” That trip will take them from a comfortable existence at their home in Berkeley, California, to a sterile and uncomfortable internment site in Topaz, Utah, “a city of tar-paper barracks behind a barbed-wire fence on a dusty alkaline plain high up in the desert.”

Otsuka's novel unfolds in five different but interconnected narrative perspectives, and moves hauntingly through the family's internment experience in the voices of the mother, daughter, son, and father. The woman and her children recount, in sober detail, the daily events of their journey to—and time in—Topaz, where besides the internees, their barracks, and the soldiers, there was “only the wind and the dust and the hot burning sand.”

California House (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)

California House (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)After the war, the family is permitted to return home. But they return to a neighborhood neither familiar nor hospitable. Their home has been vandalized, their neighbors are at best aloof or at worst hostile, and their sense of place in America is forever changed.

Though the novel tells a powerful story of the fear and racism that led to exile and alienation, Otsuka weaves a compelling narrative full of life, depth, and character. When the Emperor Was Divine not only invites readers to consider the troubling moral and civic questions that emerge from this period in American history but also offers a tale that is both incredibly poignant and fully human.

Major Characters in the Novel

The woman

Following her husband's arrest by the FBI after Pearl Harbor, the woman is faced with abandoning her family's comfortable home and abruptly becomes sole caregiver of her two children. With a sense of both resignation and resolution, she manages to hold her family together throughout their forced internment.

“That evening she had lit a bonfire in the yard ... She smashed the abacus and tossed it into the flames. ‘From now on,' she said, ‘we're counting on our fingers.’” —Julie Otsuka, from When the Emperor Was Divine

Julie Otsuka's mother (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)

Julie Otsuka's mother (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)The girl

A child of ten when the story begins, the girl's growing sense of the hard realities of the family's situation stands in sharp contrast to her brother's innocence. Although she wears Mary Janes, owns a doll from the Sears catalog, and enjoys black licorice and Dorothy Lamour, this sense of her American identity, as well as her heritage, will be challenged by the novel's events.

“Her watch had said six o'clock for weeks. She had stopped winding it the day they had stepped off the train.” —Julie Otsuka, from When the Emperor Was Divine

The boy

An eight-year old with a child's natural instincts to make the best of any situation, the boy struggles with the absence of his father, whom he sees everywhere, even in his dreams. He passes the time playing cops and robbers and war, and interests himself in the radio and magazine accounts of the conflict overseas, but his father's absence proves a deep sadness in his life.

The father

Arrested and sent away prior to the opening of the novel, the father's presence through much of the story is seen at a distance through his letters to his wife and his children. After his extended detention at the Lordsburg Facility in New Mexico, he returns home to his family a hollow man. His narration in the novel surfaces angrily in the final chapter titled “Confession.”

- Each but the final chapter of Emperor begins with an image. Otsuka has said that her idea for the novel actually began with one: the image of the mother standing in front of the evacuation order. What do you imagine was going through the woman's mind when she read this evacuation order?

- What possible reasons might Otsuka have had in depicting in such detail the images of Americana (Woolworths, the YMCA, Lundy's Hardware, etc.) in the first chapter?

- What do you think about the United States government's choice of words like “evacuated,” “assembly center,” or “relocation center” to describe the internment camps?

- “Shikata ga nai” is a phrase in Japanese that means “it cannot be helped now.” Does this phrase influence the mother's or father's behavior in the novel? What other factors might explain their behavior?

- The boy inscribes on his pet tortoise's shell his family's identification number. In another place, we learn that the girl “[p]inned to her collar...an identification number.” We also learn that “around her throat she wore a faded silk scarf.” What might Otsuka be suggesting about the experience of internment for these children?

- In an interview, Otsuka said that she “wanted [the novel] to be a universal story, although it happened to a particular group of people.” What universalities did you find present in the story or the characters' experiences?

- Compare the views of the family's neighbors from before the internment and after. Do you notice any differences in the family's interactions with their neighbors? In what ways does the family itself act differently?

- At one point in the fourth chapter, the narrator states, “we tried to avoid our own reflections wherever we could. We turned away from shiny surfaces and storefront windows. We ignored the passing glances of strangers.” How does this reflect one of the principal psychological effects of the internment on the family?

- The final chapter of the novel is told in a much different voice than the preceding chapters. What purpose might Otsuka have wanted to serve by constructing the father's voice in this way?

- What do you think the title means? How do you see it related to the experience of internment?

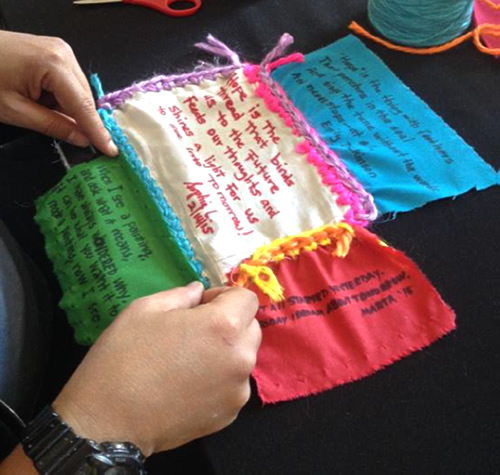

When the Emperor Was Divine Readers Knit Hope Blanket in Miami, FL

|

– from a final report by the Miami Dade College, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in 2014-15.

When the Emperor Was Divine Inspires a Japanese tea ceremony demonstration in Pittsburg, PA

|

“Gumberg Library was able to strengthen its ties and place in the campus community, working with instructors, the university president, provost, deans, students and staff. In fact, during the programming Duquesne’s President Ken Gormley began a discussion series focused on civil discourse. The themes of the program resonated with the Big Read novel and we discovered serendipitously that it was a perfect fit. We chose this novel because it is so closely aligned with our mission and being able to fit our programming easily into the President’s new initiative was an added indication of impact.

“Without the NEA Big Read support, we could never have brought the author, Julie Otsuka, to our campus. Her visit made a huge impact on over 350 people who attended her talk. This type of experience is so unique; even when authors visit Pittsburgh, the events are often expensive which limits community access to them. The NEA Big Read support allowed us freely to give away 950 copies of the novel. This had a positive impact on the number of readers we were able to reach and involve in the program. Over 1,400 people participated in our Big Read of When the Emperor was Divine and if all of them actually read the novel, we believe that the impact of Otsuka’s story will be felt in their lives for many years to come.”

– from a final report by Duquesne University, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2016-17.

Partnerships and Creative Programming Extend Reach of Events Across the Country

Throughout the FY 2014-2015 programming year, partnerships with Japanese cultural organizations helped grantees provide a cultural context. The Center for Literature and Theatre @ Miami Dade College planned a visit to the Morikami Museum and Gardens. The Salt Lake City Public Library was able to offer its participants an immersive experience with the historical events of the book through a tour of the Topaz internment camp site, located in nearby Delta, Utah, and a community member’s recollections of his own time spent at the Topaz camp. The Palo Alto Children’s Theatre worked with the Japanese American Citizens League and the Palo Alto Buddhist Temple to create a Palo Alto Day of Remembrance to recognize the impact internment had on its community.

|

Baseball Game Provides a Segue to Reading in Attleboro, Massashusetts

“Our most successful events have always been the family oriented events as well as our keynote speaker. Kicking off with baseball at our City’s 100th Anniversary was a big hit on a very hot, humid day. It brought many individuals who had not heard of NEA Big Read, allowed for a comfortable and enjoyable segue into the reading of the book. It also highlighted a very American activity that was the activity of choice by many of the men and boys in the camps. The Japanese American Cultural Day provided opportunities for families, adults, and children to try some cultural crafts, math skills, food, and to learn about Japanese Culture. Our discussions and book giveaways at three varying community events - City’s 100th, the Farmers Market and the Lee’s Pond Festival brought the Big Read to three varying locals in the City ‐ the Central, the South and Eastern parts of Attleboro. Combining a discussion, craft, and book giveaway made our table a “place to be” for all ages. The Attleboro Area Bar Association sponsored “Civil Liberties Then and Now” was so well received that many in the audience wished we had gone over the 1½ hour panel discussion.”

“Our keynote speaker, Margie Yamamoto, was very highly received. Much praise for her presentation and apology for what her family endured, were given by several audience members. It is likely that our local high school will bring her back during the year as the various English and history classes read the book.”

“The Attleboro Arts Museum art finale always defines the essence of our title and experience. The creative use of keys created a reflective environment for observers and artists to decide what is most important in their own lives.”

“The NEA Big Read has brought fellowship, a sense of community, and an ‘excuse’ for many individuals to stop in the library, the museum, or other venues to participate in what is going on. It brings a purpose and reason to be with other community members to enjoy and talk about the experience of the NEA Big Read. Of course, we have our usual followers, but each year, we see new faces, hear new personal stories, and receive more thanks for what we are doing. I believe our keynote speaker says it best when describing the impact on our community. Margie stated ‘I can’t begin to thank you enough for inviting me to speak for your Big Read project. I have been giving various versions of this talk for over four years and this was the most responsive, receptive and knowledgeable group I’ve had the honor to address. All credit must go to you and the wonderful work you did around When the Emperor was Divine.’ We had over 100 people attend‐ others are asking when it will be on cable as they could not attend. A member of the audience offered a tearful apology to Margie for what our country had done. Many community members individually let us know that they had never realized that such a thing had happened in our country. Thus, The Big Read brought enlightenment, encouragement, and engagement to our community this year.”

– from a report by the Attleboro Public Library, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2014-2015.

Julie Otsuka's mother and grandmother (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)

Julie Otsuka's mother and grandmother (Courtesy of the Otsuka family) Julie Otsuka's mother and grandfather (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)

Julie Otsuka's mother and grandfather (Courtesy of the Otsuka family)