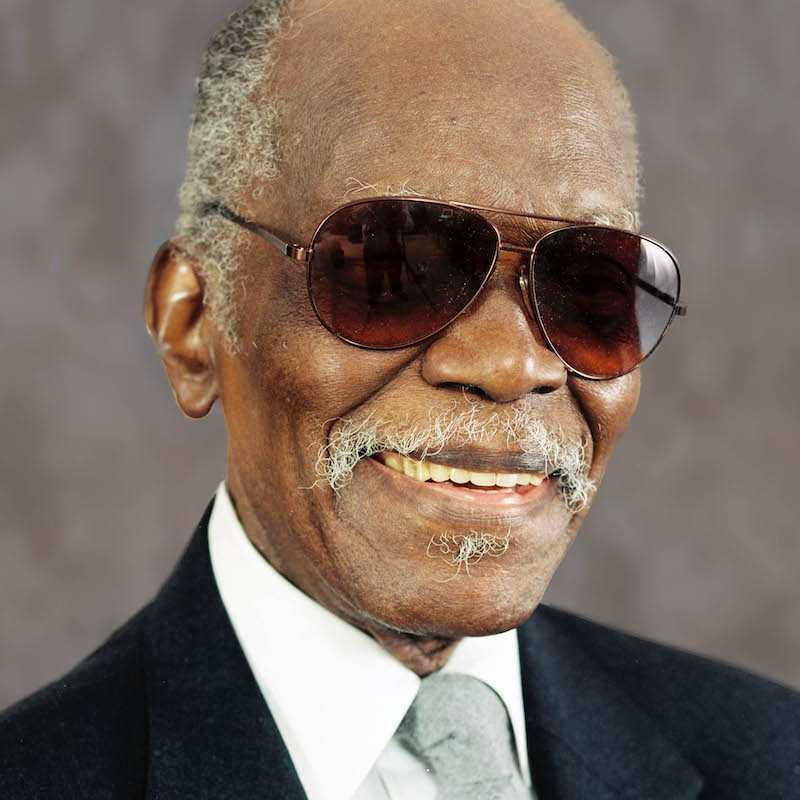

Celebrating the late Hank Jones

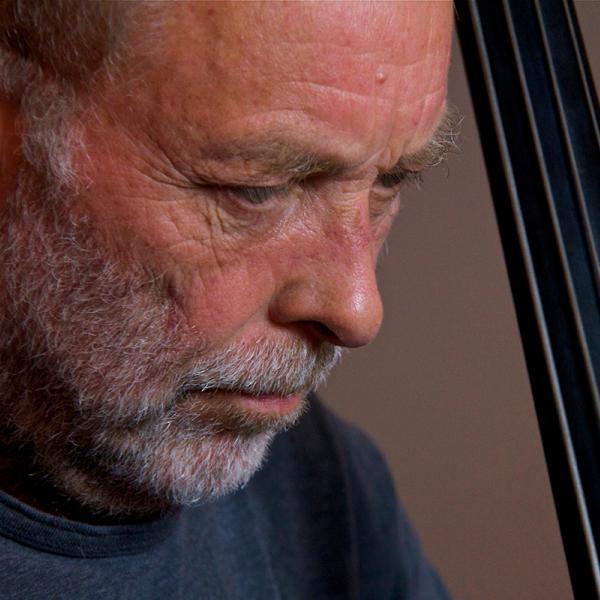

Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com

Music credits:

“Bluesette.” composed by Norman Gimbel and Jean-Baptiste "Toots" Thielemans, performed by Hank Jones. It’s from Live at Maybeck Recital Hall, Volume 16.

“Wade in the Water” from the album Steal Away, traditional, performed by Hank Jones and Charlie Haden.

“NY” from the album Soul Sand composed and performed by Kosta T. Courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Josephine Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works. I’m Josephine Reed. As we celebrate Black history month, it seemed like a good time to revisit one of my earliest interviews for the arts endowment—with one of my favorite musicians-- pianist, NEA Jazz Master, and National Medal of Arts recipient the late great Hank Jones. Although Hank passed away in 2010, he remains in many ways an embodiment of jazz history

(music up)

That was Hank Jones playing “Bluesette.” As you just heard, Hank was an elegant and lyrical jazz pianist who recorded more than 60 albums under his own name, and thousands of others as a sideman. Born in 1918 in Mississippi, he was raised in Michigan. He was a member of the famous jazz family that includes brothers Thad, a trumpeter, and Elvin, a drummer—both of whom also became prominent jazz musicians.

A performer by the time he was 13, his early influences were Earl Hines, Fats Waller, and Art Tatum. He moved to New York when he was in his twenties where he found bebop, embracing the style in his playing and even recording with Charlie Parker. He also took jobs with bandleaders like John Kirby, Coleman Hawkins, Billy Eckstine, and Howard McGhee. He toured with Norman Granz's Jazz at the Philharmonic and as a result, he became Ella Fitzgerald's pianist, touring with her from 1948-53. Engagements with Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman followed, and recordings with artists such as Lester Young, Cannonball Adderley, and Wes Montgomery, in addition to being staff pianist for CBS studios

Always in demand for record dates and tours, Hank was the first regular pianist in his brother Thad's co-led orchestra with Mel Lewis, beginning in 1966. Jones continued to record and perform throughout his life, as an unaccompanied soloist, in duos with other pianists (including John Lewis and Tommy Flanagan), and with various small ensembles, notably the Great Jazz Trio. An evolving cooperative group whose original members, were Hank, Ron Carter and Tony Williams.

I’m barely scratching the surface of the accomplishments of this jazz legend. But let me give an abridged list of some of his honors: In 1989, he was named an NEA Jazz Masters; in 2003 he was given the ASCAP Jazz Living Legend Award.[4] In 2008, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts; in 2009, he was honored with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

I spoke with him in 2008 and was nervous--I had been in awe of him and his music. But my overriding memory was of an elegant and humorous gentleman who put me at ease and charmed me as he spoke about his life in music and some of the people he played with. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

Okay, Hank Jones, I’m going to start with a very easy question.

Hank Jones: It will have to be easy because I, I don’t know the hard answers. <laughs>

Josephine Reed: <laugh> What makes jazz, jazz?

Hank Jones: “Ooooh,” you started out with a hard question, right? Well, I think the fact that there is a lot of improvisation like to, you have to… See when you play jazz you, of course, you have to know the melody of course, whatever you are playing. Then you improvise on the melody, which means you play variations of the melody. And it’s a sort of freestyle, it’s a loose style. It’s relaxed, I think. That’s the–probably the short answer. I don’t know the long answers.

Josephine Reed: I know as you say one needs to be very relaxed. But it always seems like an incredibly brave thing to do.

Hank Jones: Well, in the senses that you’re always exploring new territory. You’re always doing something else. What you try to do is you try to vary your playing so that you, you're always playing something different. You don’t want to keep playing the same thing. You don’t want to get into musical cliché. So I think that’s, that’s one of the problems you have to watch.

Josephine Reed: Now you come from a very musical family.

Hank Jones: Well, I was lucky enough to be in a family that included Thad, my brother, and Elvin. And also I had two sisters. I had a younger sister, she also played piano. And then my youngest sister, Edith, who didn’t play but she sang. You know, of course that and Elvin, and my father played guitar. And my mother played piano.

Josephine Reed: Now, there was a lot of church music in your home?

Hank Jones: Yes, there was. Early on, I heard a lot of gospel music; hymns, spirituals, and I was particularly fond of spirituals. And I still am to this day.

Josephine Reed: Can you talk about the crossover from moving from a house with a lot of church music to then exploring jazz, and how you ended up being a jazz pianist.

Hank Jones: Well, it’s not that well defined because the crossover was gradual. I started playing church music gradually. I took lessons and my teacher taught the scales and exercises. And also short pieces that were not jazz related, that were short, semi-classical pieces. And later more classical pieces. But then when I started hearing all the jazz being played by the player pianos and also by recordings, see, my mother and my father had a tremendous collection of records, records of all types; blues, jazz records. So I heard a lot of music. And I, I think in hearing this music, it was a gradual transition let’s say to something in my mind said, “Well, maybe if these people can play this way, why can’t I do this?” You know, so, I started to experiment. And that’s how you start. And experiments resulted in disaster as you can see.

Josephine Reed: Hardly. Now you mentioned Fats Waller. He was an early influence.

Hank Jones: Yes, he was. Certainly. Fats Waller, I think influenced my playing a lot early on. And then there was Teddy Wilson, and of course later on the great Art Tatum.

Josephine Reed: Tell me the first time you heard Art Tatum?

Hank Jones: The first time I heard Art Tatum <laugh>, I, I couldn’t believe it. I said to myself, this is a trick. No one person can play like this. There has to be at least two or three people. That, that was my impression of Tatum. And, it lasted a long, long time. Probably when I first saw him in person. I realized that it was just one person. I was still amazed. And when you watch him play as I got a chance to do later, you could not believe the things he was playing because there was very little arm motion, body motion. He did it all with his fingers, everything he did. And it was quite amazing. And still is to this day.

Josephine Reed: Your brother, Thad, was a horn player.

Hank Jones: A great horn player. Played trumpet, and cornet also.

Josephine Reed: And Elvin, a drummer…

Hank Jones: Yes, yes, Elvin was a fantastic drummer who never studied drumming officially taught by a teacher. He learned. He was in the Airforce and was in one of the Airforce bands. And that’s how he learned to play. Also he was a great fan of Buddy Rich. He loved Buddy Rich. I used to be with J.T.P., and whenever we’d play Cleveland, Elvin was stationed at a Airforce base near there. Elvin would be at the concert listening to Buddy Rich.

Josephine Reed: Did you get a chance to play with your brothers often?

Hank Jones: Not as often as I would like to have, you know, because I preceded them by a few years, you know. They were quite a bit younger than I. Elvin and Thad played a lot together more than the three of us ever played together. See, in Detroit, where Elvin sort of got to have most of his activity, he played in a band, like a house band at a club there in Detroit. Where a lot of players came through, play– players like J.J. Johnson, several of the horn players, Dizzy, Miles Davis, people like that. They came through and Elvin was playing in the house band at this club The Detroit. So, he got to play with a lot of people. And he absorbed, a lot, I think in, during that period.

Josephine Reed: You moved to New York in 1944?

Hank Jones: Yes, late 1944.

Josephine Reed: Can you talk about the difference in the music that was being produced in Detroit at that time and the music that was happening in New York?

Hank Jones: Well, in Detroit, of course you know we had people like Barry Harris, you know, Tommy Frank who had played there. The music that I heard was primarily music in Detroit. But I guess it was a sort of, sort of jazz. It wasn’t the kind of jazz that, that I heard later on. It wasn’t called Bebop at that time. You know, because Dizzy Gillespie hadn’t made his appearance with by then <laugh> But it was, it was two-handed jazz, you know, it, the Teddy Wilson style, the Fats Waller style. And that was the style then. When I got to New York I started to be influenced by Bud Powel, people like that, and Monk, Thelonious Monk, players of that type, you know. And then, what I wanted to do was to, to retain some of the style that I had previously. But also to absorb some of the, of the different styles that I heard, which was called erroneously, I might add, Bebop.

Josephine Reed: You know, you don’t like the term Bebop. Tell us why?

Hank Jones: Because I really don’t think it adequately describes the type of music that is being played. I think a better term would be, I don't know, you could even, you’d use the term experimental music, although that has certain connotations that I don’t want to get into, and not the extreme. But I think it was different, yes. It was a little more complicated. You had to have, let’s say, a deep understanding of harmony. And you had to also have certain flexibility in playing what other instrument you played the piano, or trumpet, or saxophone, whatever. You had to be very, very fluent. The style was very complicated. So, when they call it Bebop it doesn’t describe what they’re really doing. What they– what they’re doing is actually playing an advanced form of jazz, at that time.

Josephine Reed: I think, was it Dizzy Gillespie who said Bebop was, you were playing the notes between the notes?

Hank Jones: I don’t know that I agree with that or not because if there is no space between the notes but you could–– that you could play. <laughs>

Josephine Reed: But when you listen to Charlie Parker, it kind of makes sense?

Hank Jones: Well, Charlie Parker, yes, of course. Charlie played a nice, moving style. Don’t forget, Charlie’s roots were from Kansas City, so you could say, his playing had a–– was a very strong blues influence because there was a lot of blues played in Kansas City. So everything that he played came out of that.

Josephine Reed: And you played with him?

Hank Jones: I played with him on certain recordings but never in a nightclub.

Josephine Reed: And what was it like recording with him?

Hank Jones: Fantastic, exciting, and stimulating. You had to think in order to play with him because he, he played such a variety of things. Changes, we call them; core inhibitions, substitutions, and so forth. And you had to be really on your toes to play with him. I enjoyed it but it was a mental exercise for me. <laughs>

Josephine Reed: <laughs> Yes. And you also played with Ella Fitzgerald for five years.

Hank Jones: Four, it was actually about four and a half, you know. It was a great experience for me because of the different mode of playing. You had to learn how to accompany, you see. Accompanying is quite different from playing solo. When you’re accompanying a soloist, be it a vocalist, or an instrumentalist, you have to play in a manner that is complimentary to the soloist, but you’d never interfere with the soloist. You’d provide support but you’d never overshadow. You play in the background. You play, you’d provide a platform for them to play; harmonically and melodically, and whatever it takes. So, it means that you have to listen very carefully to the soloist. You compliment the soloist but you never interfere. You play in the open spots perhaps. But sometimes you lead a little bit but never to the point where you interfere with the train of thought of the soloist.

Josephine Reed: That’s the difference between being a soloist and playing for someone, or with someone. What about the difference between playing for someone like Ella Fitzgerald and playing with Charlie Parker, for example. The difference between playing with a singer?

Hank Jones: Accompanying Ella Fitzgerald, you see. You had to think in two modes. You see, Ella was a very fine ballad singer. She was one of the greatest. Also, she could skat sing with the best of them. So, when she sang skat, you had to alter your style just a little bit, you know. My style basically, in accompanying was the chord style, you know. That is, I didn’t use the single finger fills that a lot of pianists use. I think when you use single finger fills this is not a criticism. But I think you tend to interfere with the train of thought of the, the singer. You don’t want to do that. So I played sort of block chord fills. I did that quite a bit also with playing behind Charlie Parker and soloists of that type because you had to provide that harmonic background, exactly. So there had to be sort of a floor for them. It’s hard, it’s hard to describe. But it, it means that you had to lay down, as I, if I may say that a pattern of chords that is complimentary to what they were doing.

Josephine Reed: Can we play something of yours? I’d actually like to play “Bluesette.”

<song plays>

Josephine Reed: Well, Hank Jones?

Hank Jones: Well, I, I don't know. Who was that playing?

Josephine Reed: Who was that playing first of all? I’ve listened to that and I think whosever playing this is bringing so much joy to it.

Hank Jones: “Hmm,” well you know, I, when I’m playing something, I think of something pleasant. I think it requires thinking in a certain mode. It may be, might be better to say, “thinking in a neutral mode,” because you don’t want to be influenced by anything that you’ve ever heard before. So, I think you’re starting from zero and you can go from that to wherever you’re going, wherever it ends up.

Josephine Reed: What strikes me is …

Hank Jones: Hopefully it won’t remain at the zero level of that song. <laughs>

Josephine Reed: But it seems to me with jazz it’s always a collaboration, no? Between the composer and the musician.

Hank Jones: It is because what you’re doing is you’re playing on a format that was created by the composer. And that’s one thing I always try to do. I try to establish the melody that the composer had in mind because that, if you don’t then you’re really playing in a vacuum because the composer must have had something in mind when you wrote to him. So you try to be true to what the composer had in mind even with your improvisations. Because you always have to keep that melody in mind. And also that harmonic progressions as well. Well, that’s what improvisation is. I mean, you have to create a different line. A variation of the original line, of the original melody, so to speak.

Josephine Reed: How often do you practice?

Hank Jones: When I’m at home I try to practice about three hours, if I have the time, you know. When you’re on the road it’s hard to do unless you have a, a portable keyboard that you can take it with you. But when I’m at home I practice three hours, three and half, or four, or something. I try to keep in shape. If you can’t play what you think of then something is missing. It all happens very quickly. You don’t have time to think so to speak when you’re playing. Because you will have established all of that prior to that. And your, your technique then follows. Your technique is first, because if you don’t have that you can’t perform, you can’t play anything.

Josephine Reed: That’s the thing that always impresses me because not only is it being improvised but it happens so quickly.

Hank Jones: Yes… it happens instantaneously. You’d think of it as you play it. And so you’re always thinking ahead. I think that may be the key. I’d, for instance, if you, if you’re sight reading. I think one of the keys is, is you have to think maybe two or three measures ahead. Just to look ahead to see what’s there. While improvisation is almost like that because you’re thinking of the chord progressions, two or three bars ahead. So, when you get there, you know, you’re in, you’re prepared for it.

Josephine Reed: You spent, what did we say, almost 20 years working at CBS?

Hank Jones: Seventeen to be exact.

Josephine Reed: Seventeen to be exact. Why did you choose to work at CBS?

Hank Jones: Well, it happened, sort of by accident, you might say. I had first done some recordings with Andy Williams, the singer. And after the recordings Andy did he moved to CBS. And he asked me to play on that show. So, I was fortunate because Andy Williams brought me along and I got the job at CBS. And then subsequently I was put on the Gary Moore show. And I did that for oh, about 17 years. So I was pretty busy, you know.

Josephine Reed: And then you left CBS and you went back to playing clubs.

Hank Jones: That’s right. And we called it freelancing. I used to freelance. And I’d get calls from a contractor they say, “Are you free next Thursday at two o’clock?” I said, “Well, I’m not free but I’m reasonable.” [laughs] Sorry about that. But, I did a lot of freelancing, and recordings, and so forth. I did some work with bands like Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Coleman Hawkins small groups. And of course there was a bit of recording connected with any, each of those. So, I got a lot of experience in various formats.

Josephine Reed: Is there any format you like best?

Hank Jones: Well, I have to say that I like solo playing best, although a close second would be duo with bass. As a close third would be playing with trio base, and drums. But I think, I believe I like the solo form best that’s because I think it gives you more freedom that you can explore things that you wouldn’t dare to do if you were playing with somebody else because they couldn’t possibly follow what you’re doing, unless they knew it in advance what you were doing. So I like, I like the solo format best.

Josephine Reed: And tell me how did you hook up with Joe Lovano with him?

Hank Jones: I had, I had heard of Joe, strangely enough, when I was doing some things out in Idaho, with doing the Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival out there a few years ago. But Joe was on one of the, one of the programs there. I didn’t get to play with him at that time but I knew about him. So, consequently when he came to New York to do a series of engagements he called me. And he was doing, calling me to do a duo. And there– there’s the duo format again that I enjoyed doing. So I played with Joe during which time I also had a chance to play solo. Because when Joe wasn’t playing it was solo. So, I was able to do both things. I had the best of both worlds.

Josephine Reed: And you also made a great CD of spirituals, called, Steal Away.

Hank Jones: That was with Charlie Hayden, a bass player.

Josephine Reed: And that seemed like an unlikely duo as well. I mean, Charlie Hayden doing this. But yet, it’s absolutely gorgeous.

Hank Jones: Well, thank you. I enjoyed doing it because as– as you know, I think I may have mentioned the spirituals. I grew up listening to spirituals. You know, the strange thing is Charlie and I actually played a concert in Montreal together, during which we played half the program spirituals, the other half, jazz. It was a sort of a combination of two things. When we went into the recording studio, the A and R man said, “Well, why don’t you record the things that you did in Montreal?”

So, that’s something we did. It’s how that came about. And it was a great experience, and I loved doing it at night. I liked playing with Charlie. So, it was, it was great. I loved playing the spirituals. I love spirituals. Yes.

Josephine Reed: And 1974, you went to the White House. Tell us about that?

Hank Jones: Yes. They were, they were doing at that time a celebration of Duke Ellington’s 75th Birthday, I believe it was. So he was invited to the White House. And I played it with an orchestra there.

Josephine Reed: And that was a great evening at the White House. Duke Ellington, I worship at the altar of Duke Ellington.

Hank Jones: As we all do. <laugh> Yes, you know, by the way, Duke Ellington was one of, was Thad’s inspiration for writing. Although he did not write like Ellington, Ellington inspired him. And Thad was a really great arranger and composer.

Josephine Reed: And you’ve often felt that he has not gotten his due.

Hank Jones: I believe that. I think he should have been more appreciated, the band. The band should have had, gotten more recognition. Of musicians, people that, that know about music appreciated that. But not the general public I think and that, that’s too bad, because he was a great composer, and arranger and player. A lot of people don’t know that Thad was one of the greatest trumpet players that ever played. You see, when he had the Big Band he had three or four trumpet players in the band. He allowed them to do most of the solo work because he was conducting. But the cognoscenti recognized his ability and his talents.

Josephine Reed: Your brother’s aside. If you had to name any two or three composers you just love to play, who would they be?

Hank Jones: J.J. Johnson, Charlie Parker, of course; Tad Dameron, perhaps, yes. Because they were the foremost composers of that, of that kind of music at the time. Their music still exists. People are still playing it. Sometimes they don’t even realize that they’re playing it but they are.

Josephine Reed: And is there anyone that you particularly loved playing with?

Hank Jones: Well, of course, you know, I loved playing, accompanying Ella Fitzgerald. I loved playing with the Benny Goodman Trio when I was working with Benny, and the quartet. And of course I enjoyed working with Joe Lovano, who I think is one of the greatest tenor saxophone players around in any time. Oh, with Charlie Parker of course, but, see, my work with Charlie Parker was very limited because I only did recordings for him. See, he did the tours, a couple of tours I guess was it, with J.T.P. at the time. When you did tour the Norman Granz and the Jazz at the Philharmonic. During the off time you did the recordings.

Josephine Reed: Can you talk a little bit about Norman Granz. He’s had such an impact on jazz.

Hank Jones: Well, I have to give Norman Granz credit for bringing jazz, let’s say, to a lot of people that might never have heard it before. He brought jazz to concert halls. He brought jazz to a lot of communities that probably had never heard jazz with players like Charlie Parker or Bill Harris, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Buddy Rich–– people like that, in person. Norman Granz was responsible for that. Also, he broke the color line, in some places in the south. The color line was a very real thing. He insisted on mixed audiences. Previously that had not occurred, you know, so he deserves a lot of credit for all he did.

Josephine Reed: And the body of recordings that he left behind is, it’s monumental.

Hank Jones: Yes. And I guess it were a series of what? Eight, or seven, or eight, I’m not sure–– of recordings of J.T.P. I think, close to Volume 8, I believe. I should know. But I did, I did a lot of them. It was always a great, it was a great experience, because sure, I mean, you got to play with people. When I first came to New York you see I had heard about people like Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young by reputation. I had never seen them before. And look, on J.T.P. I got not only to see them but to work with them. So, it really was a great experience for me. And a great learning experience. As everything else is. Everything that I do is a learning experience. I’m still reaching for that, goal.

Josephine Reed: You made your first album 61 years ago.

Hank Jones: Did you have to bring that up?

Josephine Reed: I’m sorry, I was just wondering. Okay, now, somebody listening to this <laugh>… let’s just say they wanted to hear…

Hank Jones: <laugh> No, I’m kidding. I’m kidding, you know I’m kidding you.

Josephine Reed: I know, I know. They wanted to hear the best of Hank Jones. Or, what your favorites are? What would you recommend?

Hank Jones: You know, but I don’t really, sincerely, I don’t have any particular favorites.

Josephine Reed: You don’t, okay.

Hank Jones: I’ve enjoyed everything I’ve done. And everything I’ve done, I’ve tried to do the very best I could. So, I, you know, I don’t have any favorites because I just try, I just try to do everything as the best that I can possibly do it.

Josephine Reed: You were also given a National Medal of Arts. Can you talk about that experience?

Hank Jones: Well that was a great experience to be presented the Medal of Arts by the President. And I’m grateful to all the people who were responsible for me receiving this award. Because a lot of people of course, had a hand in it. And I’m also grateful to my parents for giving me a start in music and life. And had faith and confidence in me and my future. I’d just like to say that to me, it’s going to provide me with an incentive to do better, to do more things, better things. Providing better music. Doing my very best at all times. It’s not a period for satisfaction. It’s satisfaction plus, and hard work to do something better in the future.

Josephine Reed: Hank Jones, thank you so much. It was really, really a privilege to talk to you. Thank you.

Hank Jones: Thank you, my privilege.

Josephine Reed: That was my 2008 conversation with NEA Jazz Master and National Medal of Arts recipient pianist Hank Jones. Hank Jones passed away on May 16, 2010. As we celebrate Black history month, let’s celebrate Hank Jones, his music, and a life well-lived.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. We’re getting ready for another celebration—a concert in honor of our 2022 NEA Jazz Masters. It’s taking place on March 31 at SFJazz and it will also be live-streamed. For details and updates check out arts.gov or follow us on twitter @NEAarts.

Than follow Art Works. on Apple or Google Play and leave us a rating—it will help people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening

###

Photo Credit: Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com¸

To celebrate Black History Month, we decided to mine the archives and revisit my interview with pianist, NEA Jazz Master and National Medal of Arts recipient Hank Jones. Born in 1918, Jones began performing by the time he was 13, and he continued performing and recording until his death in 2010. His career contains much of jazz history—with 60 solo albums and literally thousands on which he was a sideman. And his family history is entwined with jazz as well: two of his brothers--trumpeter Thad and drummer Elvin-- were great and well-known jazz musicians. Always in demand for record dates and tours, Hank Jones played and recorded with a who’s who in the jazz world, including bandleaders like Coleman Hawkins, Billy Eckstine, Howard McGhee, Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman and with artists such as Charlie Parker Lester Young, Cannonball Adderley, and Wes Montgomery. He was Ella Fitzgerald’s accompanist for almost five years and served as the original pianist of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. He was an eloquent and lyrical pianist with an unmistakable style. I spoke with him in 2008 when he had been awarded the National Medal of Arts, and as you’ll hear, Hank Jones was elegant, humorous, and happy to talk about his extraordinary life in music. Enjoy!