MUSIC CREDIT:

“NY” composed and performed by Kosta T from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of the Free Music Archive.

Rebekah Taussig: I think that we often think of our bodies in really distinct categories, disabled and not disabled and that there’s a big chasm between those groups of people and in some ways there are things that are distinct about our individual experiences, but a lot of what I am trying to play with and show in the book is that we all live in bodies with limitations and points of access. This is something that we all should be thinking about and not just in a dreadful way but in a way that allows us to imagine more for each other.

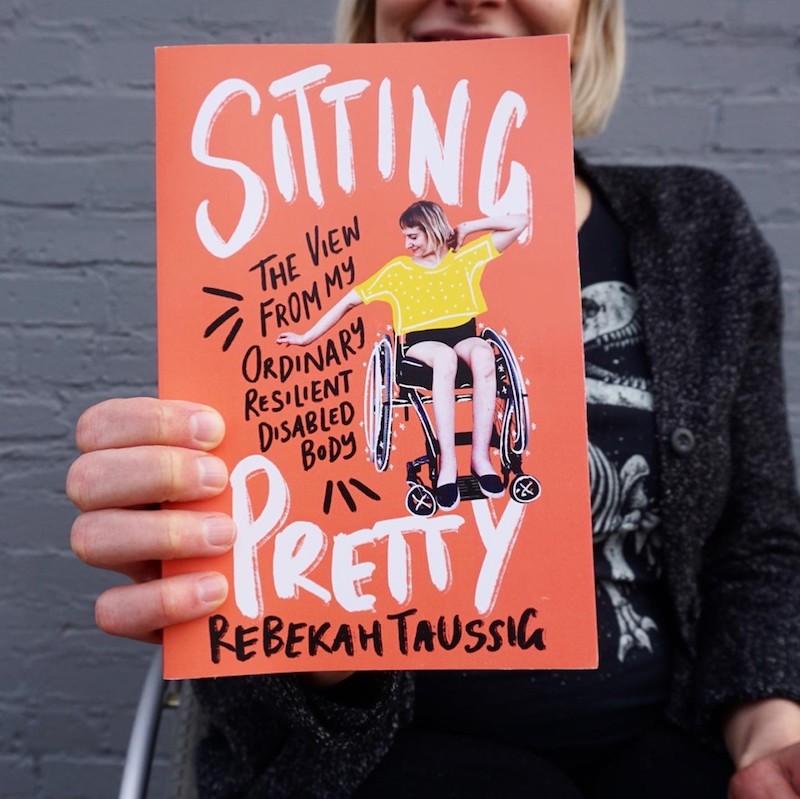

Jo Reed: That is writer, teacher and advocate Rebecca Taussig and this is Art Works the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Growing up as a paralyzed girl during the 90s and early 2000s, Rebekah Taussig only saw disability depicted in simplistic and simple-minded ways--none of which felt right. She wanted stories that allowed disability to be complex and ordinary, uncomfortable and fine, painful and fulfilling. As an adult, armed with a Ph.D in disability studies and creative non-fiction, Rebekah got to work—first by creating the Instagram account @sitting_pretty and then by writing a memoir in essays called Sitting Pretty The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body. In a conversational tone that makes it feel as though you’re talking with a very smart, funny and thoughtful friend, Rebekah reflects on a range of topics from the complications of kindness and charity to how the pervasiveness of ableism in our everyday media directly translates to everyday life for us all. Here’s Rebekah to tell us about Sitting Pretty.

Jo Reed: Why did you write “Sitting Pretty”?

Rebekah Taussig: Great question, and actually it starts a little before the book itself came into being. I started an Instagram account a few years ago now called Sitting Pretty and I created that space because I was in my late twenties, working through what my disability meant to me for the first time in my life in a critical new sort of way. I’ve been paralyzed since I was three but it wasn’t until my late twenties when I was in graduate school and immersed in critical theory on disability and disability studies and I was just saturated with-- just flooded with all of these new ideas to process and think through about myself and my body and my position in the world. And I needed a space to do that in and so I went to Instagram, a sort of-- an easily accessible spot for me to kind of hunker down and chew on a lot of thoughts in bite-size form I suppose and then attach it to an image that included my paralysis, my wheelchair, my disability that didn’t crop it out or try to obscure it or hide it but kind of brought it to the forefront. And so I’d been-- I had been doing these what I came to call mini-memoirs on Instagram for quite a few years before I started to feel the confines of that space and really want to stretch out a bit more and deepen my thoughts and expand my stories and met the right person at the right time and set to work creating a proposal for that very project which turned into the book “Sitting Pretty.”

Jo Reed: You have a Ph.D. in creative nonfiction and disability studies so a memoir and essays makes perfect sense and early on in the book you talk about growing up the youngest of six kids and partially because I’m an only child I was--

Rebekah Taussig: Oh, my, we’re so different.

Jo Reed: --just mesmerized reading about your family and your place in the family and the way they responded to you and I’d really like for you to talk about this.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. It’s interesting. When we grow up in our own families, and you I’m sure would have your own version of this, it- it’s kind of funny when outsiders start to look in and point out what’s interesting or noteworthy about your family because to me for most of my life my family was just the most ordinary group of people and their response to me was completely ordinary and then the more I wrote about it and the more people that read about it they were like “Well, that is very interesting” and I was like “Really? Oh, okay, guess it is.” So it’s just been kind of fun for me to see my family with outsiders’ eyes I guess because when I was first diagnosed with cancer and started going through these pretty intense treatments, chemotherapy, radiation, two surgeries my family-- so I was the youngest of six. I was fourteen months old when this all first started. My oldest sibling was-- would have been fourteen when all of this started and then every two years there was a new kid about, uhm.. and this would have been the ‘80s-- late ‘80s and my family really just continued on kind of as normal, as normal as could be. So they didn’t really make accommodations around the house as I started to lose my mobility-- or my-- as my mobility shifted. I mean I continued to sleep on the top bunk of the top floor of the house even as I wasn’t walking anymore, which again is one of the more notable details to outsiders but to me at the time and even for quite a bit as I got older it still felt really ordinary for me to continue to sort of make my way up to that spot on the top floor. I had a lot of pride in having the top bunk; I kind of had waited for that position in the bed lineup with all my siblings. So I just kind of found my own ways to move around whether that was up a flight of stairs or outside around the neighborhood and with neighborhood kids and kind of just folded into my family in a way that was-- felt very ordinary. We didn’t really make a big deal out of disability as a-- with a capital ‘D’ I guess, which is in large part I think why it was so striking to me decades later when I started to really think about what this meant to me because we didn’t talk about it that way at the time. My parents didn’t really-- and I think for good or bad; I think there are benefits and drawbacks to this but they didn’t really go out of their way to connect me with the disability community. There was no conversation about Rebekah has a disability and the rest of her siblings don’t. I don’t remember ever really sitting down and talking much about it at all or really talking about specific unique plans for how I was going to grow into adulthood or what it would be like for me to find a job or look at colleges versus my siblings. There was not any sort of spotlight in-- on me in that way so-- which kind of made for an interesting growing up as a disabled person because of course I am different from my siblings even as I am the same as them. And so not having any space or language to process that part of my identity and figure out for myself really what it did mean to me kind of hampered me in some ways even as it also made me-- I don’t know-- kind of scrappy and resilient so it kind of worked in both directions I think.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I’d think it would. I wouldn’t assume it was perfect but I think there was a confidence that you could maintain because that also meant you had the freedom to get on with it.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, absolutely. They definitely were not expecting me to whimper on the sidelines or get special favors and I-- and like I talk about in the opening of the book I think one of the strongest mantras in our family to this day is nobody’s whining about anything; <laughs> we’re not going to sit and wallow about anything even-- and I think this is the part that’s so remarkable to outsiders-- even childhood cancer and paralysis.

Jo Reed: And there we go, extraordinary. You talk about ableism a lot in the book and I’d like you to tell us how you’re using ableism and how you’re defining it and your thoughts about it--

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah.

Jo Reed: --of which there are many.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, exactly. I was going to say in the book there are several pages of kind of elaborating and wandering around that term because it is a loaded word. I mean it’s an “ism.” A lot of people I think come to that word and think that they know what it means and think they have a pretty sturdy understanding of it and I think that the Oxford English Dictionary version of it is “discrimination against people with disabilities,” which is pretty straightforward, but in my work and my understanding-- I mean both from an academic sense but also from a lived experience I think it’s much more complicated than discrimination against disabled people. I think it’s a hearty world view and set of structures that fill the world with a largely imagined ideal body at the center of it so the ways that we come to see ourselves in the world are kind of morphed by this large vision in the middle of it. So we shape our ideas about love and romance, we shape our stories on screens, we shape our schools and work spaces with this idea of an idealized typical body at the center of it and then any body that deviates-- the greater the deviation from that the greater the punishment to the person who embodies the literal body but also the mind or the capabilities that deviate from that idealized body in the center. And I think if you kind of start to unpack it a lot of times we talk about that as if that’s the typical body in the middle, that we shape the world around a typical body, but I don’t think that that’s really the case. I think that very few bodies actually match that idealized young, never aging, never in pain, never needing anything, never lactating, never having a period, never needing to go to the bathroom, never having a need of any sort, and that’s sort of the body that we hold up and build our world around when—

Jo Reed: Exactly.

Rebekah Taussig: --very few-- and even if you do happen to match that body for a time in your life it’s going to be a flash of a moment of time because you will age, we all age, and I know we like to pretend otherwise but we do; we all age and wrinkle and start to forget things and have different needs as time goes on. So yes, that is my-- that’s my attempt at a succinct version of that definition for that big, heavy, complicated word.

Jo Reed: As we talk about ableism, you talk about for example being able to find an apartment, a house for you to rent that you actually could have access to and said that was a job unto itself.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, absolutely, and interesting that you bring that example up because I-- before having to do that I don’t even know that I would have understood just the extent-- the barriers that I would find in my attempts to find accessible affordable housing and as a disabled person you’d think I’d be the expert on that but there’s a lot of ways in which I think we don’t understand or know how much we’ve overlooked a specific population until we’re in it, until we get to that point ourselves and realize, oh, my goodness; wow; this is almost impossible; how is a person supposed to go about doing this? I live in Kansas City and the house I live in now-- well, I haven’t moved in quite some time because I’m not about to go through that ordeal again but about five years ago now I was in a position of needing to find a place to live pretty quickly and that turned into nine months of looking for anything that I could both afford and get into and it seems like a pretty low bar but it was a surprisingly exhausting experience. <laughs>

Jo Reed: You talk also about if you go out to eat in a restaurant the kind of reconnaissance you have to do.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, really any sort of outing outside of my house. It’s like any place that I haven’t been before there’s quite a lot of research and planning and often honestly anxiety that goes into that experience so I talk about the experience of someone casually offering to go out to dinner somewhere or a birthday party that’s being held at a restaurant, and that turns into hours of Google imaging and trying to find pictures of the inside of the restaurant and seeing what the spacing is like and does it look like there’s a place that I could park to get into that building and what about bathrooms; are there going to be accessible bathrooms there. And some days I feel like I have the energy to take that on and a lot of days I really don’t.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I hear that.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, and I think my upbringing in some ways made me into a person that feels kind of up for a lot and is willing to be flexible and roll with the punches but I think anyone at a certain point gets kind of exhausted from that as a way of life, and so of course there are plenty of times when I just send the “I’m not feeling very well” text and just end up passing on a lot of the experiences that I think otherwise I would enjoy, I would in-- appreciate, but yeah, it’s kind of finding the places that work, finding the spots that I can access pretty easily and those are the places I go to all the time.

Jo Reed: And I think it also brings up that ADA was wonderful, the Americans with Disability Act, but it’s 30 years after ADA and the ableism that you’re talking about it still structures basically the way we move through the world and I wonder what you wish policymakers understood about city planning.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. That’s such a great question and I love the opportunity to answer it. It’s interesting that you bring up the ADA because I think a lot of people-- if they know what the ADA is, which a surprisingly large number of people don’t-- I think people assume that that is kind of a one-and-done deal like we’ve done it, we finished, big, giant checkmark, we’ve accomplished accessibility—

Jo Reed: Problem solved.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah, problem solved, and in some ways-- it’s both/and. In some ways it’s true, that was a huge accomplishment and remains a huge victory for the activists that fought so hard for that, and also at the very same time there is such an uphill battle to have that legislation implemented in meaningful and comprehensive ways. So in terms of what I wish policymakers knew or would have in mind I think a lot of people think of accessibility as this extra thing to kind of tack on the side of what already exists like the ramp that goes into the back of the building or like the extra sort of lift that we harness to the side of a restaurant, but I wish that what people-- I wish that people thought about accessibility as more than this extra side thing for this very few set of people and more as an opportunity to just design more sustainably and more-- widespread inclusivity. I wish that we were thinking about access with a lot more energy and excitement and creativity and thinking not just how can we get that one wheelchair that might show up into our building but how can we just create more points of access for all of us because that’s what I think we find time and time again when we actually look at design and accessibility is that when we have access in mind and we’re forced to kind of think about things more flexibly like what additional needs might show up to this space and how can we create an object or an entrance that has more points of access I think that when we’re thinking about design that way we usually get the most exciting, most open spaces and tools that everybody can use that are not just these extra add-ons for this tiny subset of people. I was just talking to someone today who was visiting their disabled son who had actually had a house that was designed specifically for their disabled body, which is a huge privilege, most disabled people are not able to actually do that, but she was saying that when she went into this house it was like “Oh, my goodness. I want this to be my house. This house it just feels good to be in it” and I think that that’s true. You don’t have to use a wheelchair in order to benefit from designs that include wheelchairs, you don’t have to be deaf in order to benefit from tools that are created with deaf people in mind, and I guess that’s what I wish that we were thinking about. I guess that’s the tone that I wish we had in conversations where we talking about and thinking about access.

Jo Reed: I know this is so early on but I’m wondering how the pandemic in fact might impact the ideas that you put forth in the book because suddenly all of us have to be aware of our bodies and their vulnerabilities and it also seems to me that in the middle of all this awfulness there’s space for imaginative thinking, for adaptability, for flexibility. There’s an opening created here I think.

Rebekah Taussig: A hundred percent I feel that and I think a lot of disabled people feel that. I think there-- depending on who you talk to and when I think that there is on the one hand a little bit of frustration that we’ve been saying there were changes that we should make and things we’ve been asking for for so long and for so long people were like “That’s impossible. We can’t do that” and then when nondisabled people have those needs then suddenly magically they appear and there’s a little bit of frustration with that, but also I think there’s a lot of excitement and hopefulness maybe even more than anything, hopefulness that these would be changes that we would be able to hold onto even when the pandemic is over and that that attitude of creativity and thinking about ways to be more flexible would be held onto. I feel really hopeful about that. I hope that that’s something we can continue to be thinking about and an approach that we can continue to implement.

Jo Reed: I would bet that out of all the essays in your book the essay on kindness is the one you talk about the most--because people want to talk about it.

Rebekah Taussig: <laughs> It’s certainly the one that people have a lot of questions about and and/or pushback. It definitely makes people uncomfortable more than anything in the whole book. Yes, yes, you’re right. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Describe the points that you were making in that essay.

Rebekah Taussig: I think a lot of times when people think about disability one of the first things they think about is kindness, that we know that we’re supposed to be kind to disabled people and we have charities around that kind of kindness and we know that as one of my students so aptly says that I quote in the book-- if we see someone who’s disabled and we don’t help them we kind of look like a jerk. And so I think we think that we understand the relationship between disability and kindness, which is that you should always be kind it’s as simple of that, and what I do in the chapter is kind of blow that wide open and look specifically at what is genuinely actually kind in a lasting sort of way when we think about disability and disabled people and the needs that that very diverse population might need at a given day. So I start by looking at some of these articles that you see crop up in the news-- quote, unquote, news where there’ll be the story about the football player who asked the disabled girl to prom and there’s a whole story about that kind of celebrating and implying that nondisabled kids are asking a girl to prom or when somebody helps a disabled person get their food at a fast-food restaurant. I think we’ve all seen those stories in the news and so I kind of begin by looking at those stories as a way of unpacking why some of those ways of thinking about kindness are actually the opposite of kind, that they so often center the nondisabled person as the star of that story and we’re actually not even looking at that experience through the lens of that disabled person and the whole story is about applauding kindness of this one time that this nondisabled person reached out to a disabled person. And then there’s so much that’s left unaddressed like why are we not looking at how to create fast-food spaces that make it easier for a disabled person to get food on their own. So that’s kind of the beginning of the conversation. I look at charities and the history of charities a little bit and then--and I think this is the part of the chapter that you may be thinking of Jo, the part that people push back against a lot-- I look at specific encounters that I have with people who are attempting to be kind to me that usually end with me feeling frustrated or humiliated or probably more specifically left really unseen or invisible. And specifically, for me this shows up with people kind of rushing to help me put my wheelchair together like in a parking lot or people asking to pray over me to heal me of my paralysis, kind of these one-on-one moments where people are attempting to do something kind but ultimately it leaves me feeling very small. And I think that that’s the part of the chapter that I think most people get really riled up about because what I hear a lot of people say are things like “Why-- I just open the door for everyone.” I think ultimately in that chapter I have to think a lot and I have spent some time thinking about my own impulse to be kind in different contexts, not specifically with disability necessarily but just when you encounter a person who belongs to a group that is disenfranchised or marginalized in one way in another there’s this impulse to get rid of that feeling that you have access to something that somebody else doesn’t and oftentimes that we respond in sort of a gut reaction as opposed to stopping and listening and looking and seeing the person who’s actually in front of us. I am read as being helpless in a lot of areas that I am not helpless but there are ways that I need help or assistance that might not be as obvious, and so I guess in that chapter ultimately what I want to do is I’m imploring people to look at each other in the eyes and really see each other before jumping to conclusions, before rushing to do something or treat that person in one way or another because more often than not I think in that-- in the space-- that beat we could take where we pause and we actually look at the person in front of us we might see something that we didn’t expect; they might be showing us something that wasn’t obvious to us in that immediate reaction. I don’t know. Is that the gist do you think, Jo, in what you saw of the chapter?

Jo Reed: Yes. Even as you’re talking I’m thinking people’s ability, and I will own part of this as well, to be unconscious as they move through the world is really extraordinary; that is something that never ceases to amaze me and as I said about myself as well. I think you’re asking people to be more conscious and I think there’s also a way in which-- and I’m completely compressing this-- you’re saying, “You see a wheelchair. You don’t see the person in the wheelchair.”

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. Yes, absolutely. I mean yes, time and time again-- it’s interesting-- the parking lot is always an interesting example to me because I put my chair together and pull it apart; pre pandemic days when I was actually leaving my house more often I would do that like five times a day and that’s something I’ve been doing since I was 17. So the process of getting my chair in and out of my car is like brushing my teeth, is like doing laundry, is the easiest thing in the world to me and I think I’m showing that I’m competent, right. I’m doing this with ease, I’m doing it quickly, I’m not struggling, but I think that as soon people see a wheelchair they-- there’s not that space between what you see and then taking a beat and waiting to see what the story actually is unfolding in front of you. They don’t have time to see competence, they just see the wheelchair, and I think so often wheelchairs are shorthand for weakness or helpless or needing help and that’s not the case in that moment for me and it- it’s pretty amazing how often-- how consistent that pattern is when I go out in public. And to me it just signals exactly what you said, that we-- and myself included we are often on autopilot when we go out in the world and so what happens is that we reveal a lot of assumptions that we have just by default because we are not taking that beat to pause before we impulsively go to grab someone’s wheelchair wheel for example.

Jo Reed: When did you start writing, Rebekah? Were you a writer all your life?

Rebekah Taussig: Oh, in some ways yes. It’s evolved so much that I hardly recognize what I was doing before as writing. I mean I started writing really excruciating poetry as a child and I wrote-- I was an aggressive diary-- journal writer so I have just a whole shelf-- a bookshelf full of journals that I wrote as a child and then I was a big reader so I was a English major and my undergrad was in creative writing. I had no idea what I wanted to do with that but I knew that I loved reading and writing so I kind of hunkered down there and I wrote a lot of strange kind of like YA slipstream fiction stories in that time of my life and then I got more into the academic side of things so I wrote my MA thesis on “Moby Dick” so I was really interested in Victorian nineteenth-century British and American literature and it was actually in graduate school that I kind of went back to the creative side of things, that I had really moved into the academic writing and had been writing more papers and things that I would try to publish as articles but it was the merging of disability studies, which was on the one hand an academic way of thinking but on the other hand incredibly personal. And so when those two kind of fields merged for me is ultimately the writing that you would be reading from me now, not so much the YA slipstream fiction or the angsty poetry of my childhood but I’m sure that that is part of what has changed me as a writer.

Jo Reed: There are two things that are true with Instagram and I’m curious about how they changed with the book and I’ll start with the obvious one being first. The photographs are so important and they’re fabulous also. Did you miss that in the book?

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. I do miss that. I think that the photos are an important part of what I tend to relish about the Instagram space. I think I did try to make a lot of the experiences in the book as visual as possible—

Jo Reed: That was my next question actually, if it changed the writing.

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. I think that I did and there are even phrases that I use in the book where I am being pretty transparent about how much I want people to be able to see and feel and picture in their heads these moments and so I do spend a lot of time describing in pretty specific detail I think-- I try to at least describe exactly what that moment looked like and felt like in a way that people could picture. I hope that I accomplished that because I think it’s important.

Jo Reed: The other thing with Instagram is that you interact with readers and you have that connection and with the book especially because it’s the pandemic so I doubt that you have many readings or if they are it’s virtual. Will you miss that and were you able to replicate that at all with the book?

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. So that’s a really good question. So we’ve had a lot of Zoom readings since the book has been out which-- it’s my first book so I don’t have a lot to compare it to but I do feel like there’s this sort of vague hole in my heart that I don’t know how to picture exactly what a real-life book tour would have been like but I find myself missing that in a really nonspecific way because I have never experienced it, but just the faces and being in a room together where we are all breathing the same air I do miss that. And it’s also interesting because this is my first book so I don’t have-- again nothing to compare it to but I do find that Instagram is a space where it’s delayed but I am getting a lot of beautiful feedback from-- on the book in that space still from people who are reading it at the beach and taking a picture and sharing it in their stories So I’m able to see my book out in the world with the people who have been following me on Instagram in a way that is incredibly beautiful and rewarding to me; but I wonder, I wish, I long for, I imagine and dream of a time when I will get to meet some of those people in real life so I think that might just break my heart wide open. <laughs>

Jo Reed: It’s a book of essays. Do you have one that you feel closest to?

Rebekah Taussig: I love that question; no one has asked me that. Yeah. I feel like the chapter on love and “ An Ordinary Unimaginable Love Story”; Yeah. I feel close to that chapter in a lot of way-- in a number of ways. So the whole chapter is about being disabled and the longing to find love and be loved and to find a partner and I think in-- on the one hand that was just such a big part of my life story so far. Not to give away any major spoilers, but I got married really young in sort of this-- in the ways that a lot of young people do get married, which is for a lot of the wrong reasons, <laughs> not to say everyone young is doing it for the wrong reasons, I definitely was, and then coming out of that and how much of my identity I think is forged in one way or another around some of those decisions, either toward or away from those relationships and then finding my partner, Micah. I write about Micah in that chapter and he is just one of the best and most important parts of me and my life and so having a chapter I get to tell that story and bring him to life on the page it’s just a -- oh, the word that’s coming to my mind, I don’t love it but the word is “precious,” like there’s something precious to me and that’s treasured to me about my relationship with him that I get to share with readers and I-- and that’s special to me.

Jo Reed: And you have a P.S. because after you were done with the book you discovered you were pregnant.

Rebekah Taussig: Yes, Jo, less than 24 hours later. I mean I hit “send” on the manuscript on a Monday night and it was the Tuesday late afternoon when I was very surprised to see two pink lines on a pregnancy test and called Micah; with no ceremony or no cute “I’m pregnant” story it was like “Micah, we’re pregnant.” And then it was just unbelievable and it continues to be kind of unbelievable to me even though Otto is almost six months old this week and then Micah-- the following Tuesday we were even more shocked to find out that Micah had cancer so that was a lot for a postscript and then of course we all learned that there was a global pandemic a few months after that. So pretty much everything changed both personally and globally after this book was written and then it came out in a world that was very different than the one it was written in.

Jo Reed: Has it ever. And how’s Micah?

Rebekah Taussig: Thank you for asking because I feel like it’s very unfair of me to tell that without the follow-up, which is that Micah is doing really well. So he had a second surgery in June and his recovery from that surgery has been longer and more complicated than we hoped for but his cancer has not come back and to both of us that’s kind of the-- everything. We can handle recovering-- we are very tuned in to any test results and so far everything has come back as looking good and we’re really relieved about that.

Jo Reed: Good. I’m very glad to hear that. Finally, Rebekah, if you could have somebody get one point from this book what would it be; if somebody walked away with this point you would say, “Okay, that’s good”?

Rebekah Taussig: Yeah. Oh, and you want me to choose one I suppose. Do you, Jo? Just one--

Jo Reed: Maybe one and a half.

Rebekah Taussig: <laughs> Yeah. Okay. I think one of them would be an important one; if someone left the book with this idea I would be glad. I think that we often think of our bodies in really distinct categories, disabled and not disabled and that there’s a big chasm between those groups of people and in some ways there are things that are distinct about our individual experiences, but a lot of what I am trying to play with and show in the book is that we all live in bodies with limitations and points of access. This is something that we all should be thinking about and not just in a dreadful way but in a way that allows us to imagine more for each other, imagine a world that can bring more ease and creativity and flexibility to all of us. So I guess one of the big things I would be pleased if someone took from this book was thinking about this idea of accessibility as a project for all of us in the way that we’re all attached to bodies and to take that idea-- this is my stretching this into one and a half ideas move-- is to take that and use that as something as a point of play and imagination and creativity, that it’s an exercise that doesn’t have to be sterile and medical and dreadful but open and expansive and maybe a little bit enjoyable as well.

Jo Reed: That is a great place to leave it. Rebekah, it’s a wonderful book and congratulations.

Rebekah Taussig: Thank you so much. Thank you so much for having me here and I loved your questions.

Jo Reed: Thank you.

That was writer teacher and advocate Rebekah Taussig we were talking about her memoir called Sitting Pretty The View from My Ordinary Resilient Disabled Body. You can keep up with Rebekah on Instagram @sitting_pretty You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Subscribe to Art Works and leave us a rating on Apple—it helps people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Stay safe and thanks for listening