Revisiting Tracy K. Smith and Melissa Range

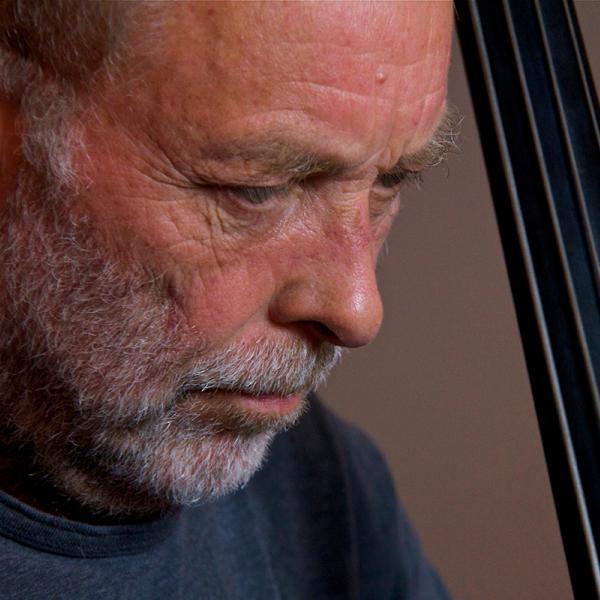

Photo credits: Tracy K. Smith, credit Rachel Eliza Griffiths; Melissa Range, credit Justus Poehls

Music Excerpt: “NY” from the cd Soul Sand, composed and performed by Kosta T, used courtesy of Free Music Archive

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed…It’s April –and we’re celebrating National Poetry Month—so today, we’re revisiting interviews with two poets. Later on in the show, we’ll hear from the former poet laureate of the United States, Tracy K. Smith, but first…. here’s an excerpt of my 2018 interview with the award-winning poet and NEA Literature Fellow Melissa Range. Her collection Scriptorium was selected for the 2015 National Poetry Series by non-other than Tracy K. Smith. Like Smith, Melissa examines the past in order to shed light on the present. Scriptorium marries the two by focusing on language—who speaks with authority? Whose language is dismissed? What do we preserve and how? The collection’s title refers to a room in medieval monasteries where the monks copied and illustrated manuscripts, and many of the poems describe in sonnet form the processes involved in creating illuminations: mixing the ink, preparing the parchment and so on. But in Scriptorium, Melissa Range also examines her Appalachian roots— the word play, the language and slang she grew up hearing—often disparaged by outsiders and slowly falling out of use. Medieval illuminations and Appalachian slang sound like an unlikely pairing, but Melissa uses the image of the Scriptorium to bring them together.

Melissa Range: I started thinking more metaphorically about a scriptorium as a place where language is taken down as if with some kind of permanence. So if I think about, you know, illuminated manuscripts and how very often they were written in Latin, but that’s not the language of the people. It’s the language of the church, but there’s always some enterprising monk who will translate it into a language for the people. And that to me shows the power of the vernacular and that the vernacular is as good as the standardized language. That was really interesting to me because also while I was writing about medieval art, I was writing a lot of poems about southern slang. My grandmothers had recently passed away and I was really interested in kind of their languages and preserving it. So once I thought about this scriptorium as kind of this metaphorical place where the vernacular language could also kind of come up and assert itself against standardized language, then I thought that was kind of a metaphor that pulled all of my poems together.

Jo Reed: I’m interested in how you connect medieval illuminated manuscripts and the language you heard growing up in East Tennessee

Melissa Reed: Well, I do think it is kind of about the level of language, the power in language that other people might make fun of or discard. And so when I think about where I’m from I think about the way that I talk, the way my people talk, and how I have been made fun of that for a long time, whether it’s my accent or the kind of southern slang that I use, Appalachian slang, and I really wanted to explore the kind of fascination for me in some of these great slang phrases. And also to kind of assert their power and that they’re not something to be mocked, but there’s a real longevity and there’s something really juicy in the language.

Jo Reed: It’s authentic.

Melissa Range: Yeah.

JO Reed: I'm from New York, another place that you really do get made fun of a lot for different reasons.

Melissa Range: <laughs>

Jo Reed: I mean it’s very, very different, but I think it’s similar in the sense that there are so many stereotypes.

Melissa Range: Right, right.

Jo Reed: And you know, the whole New York accent, which of course means you’re completely uneducated, which I have a feeling you probably share that part of the stereotype, too.

Melissa Range: Oh, yes definitely, definitely.

Jo Reed: And speaking about that, I would like you, if you don’t mind, to read one of your poems that deals with the southern vernacular and that’s Hit.

Melissa Range: Oh, yeah, I would love to. So Hit, this poem came about actually while I was in graduate school. I was studying Old English, and that’s another thing that’s happening in this book is there’s a lot of kind of working with Old English literature, Old English texts and poems. But I had heard both of my grandmothers say “hit” for “it” my whole life. So instead of saying, “It’s raining,” they would say, “Hit’s a-raining.” And I always thought that was perfectly normal except people would make fun of it. But then when I took Old English I realized it was Old English and the “H” was just still kind of there in my grandmother’s generation. I don't think it’s really there anymore. I think that is kind of dying out. My mother’s generation doesn’t use it, and my generation, we don’t really use it, either, but we know it when we hear it. So that’s kind of how this poem came about.

"Hit. Hit was give to me, the old people’s way of talking, and hit’s a hit sometimes. Sometimes hit is plum forgot and I drop the ‘H’ that starts hillbilly, hellfire, hateful, hope. Sometimes hit hits the back of my teeth and fight’s hit’s way out, for hit’s been around and hit’s tough. Hit’s Old English. Hit’s middle. Hit’s country. Hit will hit on you all day long if you let hit. When I hit the books they tried to hit hit out of me, but hit’s been hit below the belt and above, and hit still ain’t hit the sack. Sometimes you can hit hit like a nail on the head and sometimes hit hits back.”

Jo Reed: I love this poem.

Melissa Range: <laughs> Thank you.

Jo Reed: I love the rhythm of it, and I love the sensibility of it. I think it’s wonderful.

Melissa Range: Well, thank you so much. I had a lot of fun writing it, and the first time I ever read it I thought, "Can I actually read this?" It’s such a tongue twister.

Jo Reed: It is a tongue twister.

Melissa Range: And then you get used to it.

Jo Reed: There’s a lot of dialog between the past and the present that happens throughout this book.

Melissa Range: Yeah.

Jo Reed: Talk to me about what you were doing with that.

Melissa Range: You know, I don't know if I even had that much of a plan, really. I just love history and I love to write about history. There’s historical stuff in my first book, and I’m writing kind of a historical manuscript now for my third collection that I’m working on, and so I think I’m always interested in how can I see parallels between my life and lives that have gone before me, or how can I see parallel situations in the country or in the world with what has gone before? And I feel like it’s important to look at that and to kind of see what can we learn from the people who have gone before us. And then as far as the southern poems, I do think it really is at the level of language. Like I was thinking so much about old languages, and, you know, like I said, there’s some poems about Old English poetry in here, so thinking about that language. Old English becomes this dead language that no one speaks but we can read. So we can read “Beowulf” in Old English but nobody goes around speaking in Old English anymore. And I was thinking about my language, my southern language, and the fact that a lot of these phrases that my grandmother said are kind of dying out. And I wanted to think about them as living language and in some ways, I wanted to preserve, you know, kind of doing that poet’s work of preserving language.

Jo Reed: More than preserving because you don’t want it to be set in amber—

Melissa Range: Right.

Jo Reed: but to keep it vital?

Melissa Range: Yeah, I agree, to keep it vital, for sure. And for me to remember that—you know, my grandmother would say something is as "flat as flitter." Well, if I write a poem about that then I’m always going to always remember that, and I’m going to remember that I can still use that phrase. I can still keep that phrase alive no matter where I end up living. Like I live in Wisconsin now. I don’t live in east Tennessee anymore, but whether I ever go back home to live or not, I can always kind of take that language with me. So, yeah, it is preserving but it’s also more than that, like you say. It’s keeping it vibrant.

Jo Reed: There’s a poem that you-- and please forgive me. I’m going to mangle the name of the poem. Is it Ofermod?

Melissa Range It’s “Ofermod.” That’s close.

Jo Reed: “Ofermod,” like the “F” is almost a “V?”

Melissa Range: It is a “V,” yeah. It’s Old English. It’s an Old English word, and I mean it looks like “Ofermod” but it’s “Ofermod.” That’s how—well, we think that’s how they said it. We don’t really know.

Jo Reed: Okay. Do you mind first reading and then talking about that poem?

Melissa Reed: Sure, yeah. So Ofermod, I think the poem will kind of explain what this word is, but I’ll give a little bit of background. There are a couple of characters in the poem. One is my sister—you’ll learn about her—and, then, there’s a warrior named Byrhtnoth—this is an Old English name and he was a character in this poem called “The Battle of Maldon,” and this was a real historical battle. And he thought that they could beat the Vikings, he and his Old English troops, and I think that might be all I need to say.

"“Now, tell me one difference,” my sister says, "between Old English and New English.” Well, Old English has a word for our kind of people: ofermod, literally “overmind,” or “overheart,” or “overspirit,” often translated “overproud.” When the warrior Byrhtnoth, overfool, invited the Vikings across the ford at Maldon to fight his smaller troop at closer range, his overpride proved deadlier than the gold-hilted and file-hard swords the poet gleefully describes — and aren’t we like that, high-strung and ofermod as our daddy and granddaddies and everybody else in our stiff-necked mountain town, always with something stupid to prove, doing 80 all the way to the head of the holler, weaving through the double lines; splinting a door-slammed finger with popsicle sticks and electrical tape; not filling out the forms for food stamps though we know we qualify. Sister, I’ve seen you cuss rivals, teachers, doctors, bill collectors, lawyers, cousins, strangers at the red light or the Walmart; you start it, you finish it, you everything-in-between-it, whether it’s with your fists, or a two-by-four, or a car door, and it doesn’t matter that your foe’s stronger, taller, better armed. I don’t tell a soul when I’m down to flour and tuna and a half-bag of beans, so you’ve not seen me do without just to do without, just for spite at them who told us, “It’s a sin to be beholden.” If you’re Byrhtnoth lying gutted on the ground, speechifying at the troops he’s doomed, then I’m the idiot campaigner fighting beside his hacked-up lord instead of turning tail, insisting, “Mind must be the harder, heart the keener, spirit the greater, as our strength lessens.” Now, don’t that sound familiar? We’ve bought it all our lives as it’s been sold by drunkards, bruisers, goaders, soldiers, braggers with a single code: you might be undermined, girl, but don’t you never be undermod.

Jo Reed: Tell us your thoughts as you created this poem.

Melissa Range: Yeah. Well, this poem took a long time to write. I was translating “The Battle of Maldon” with a friend of mine and I hit upon this word and I said, “ofermod?” And she said, “Yeah, it’s really rare. It’s only used a couple of times in the entire Old English poetic corpus.” And this idea that mode as a word means mind, heart, and spirit all wrapped up in one. So if you can imagine your mind and heart and spirit are all the same and then that somehow translates to over proud. Once I learned that word I thought a lot about me and my sister and where we grew up and kind of the ethos of us. When I showed her this poem she said, “Oh, that’s the poem about my anger management problem,” <laughs> and I said, "Yeah, it kind of is, but it’s also my poem about me being so prideful that it doesn’t matter if I have half a bag of beans I’m not gonna ask anybody for help." You know, I’m not gonna say everybody in Appalachia is taught the same thing because that’s not true. But at least in my family we were taught, you know, don’t ask for help. Don’t be beholden to anybody. You figure it out and you make your own way. You know, I have a lovely job now being a professor at a small college and I’m really grateful for this job. For many years I struggled financially and with jobs, and so I would be really kind of scraping the bottom of the barrel, but I just wouldn’t ask anybody for help. And that overpride, when I learned that word it was a real revelation to me, that I applied it to my sister but I also applied it to myself. That word taught me a lot about me and my family and it taught me a lot about where I’m from, and I mean it was amazing to me that that just happened just because I had to translate this Old English poem, that I found this word that felt so Appalachian to me, just so hearty and grim.

Jo Reed: That’s a great story. The wonder of language—that’s what I was thinking about as you were talking. It’s extraordinary--

Melissa Range: It really is.

Jo Reed: How it can take you through generations and centuries and be all but obsolete and still so pertinent.

Melissa Range: Yeah, yeah, I agree.

Jo Reed: It sounds as though you grew up in a family and in a place that deeply appreciated language.

Melissa Range: Yeah! One wonderful thing that I got from my upbringing is just this real kind of delight in language. I don't know how true that is for Appalachian people or southern people in general. I think that at least where I’m from and in my family there is a real delight in rhyming and alliteration and word play, just people always kind of making up funny little sayings that would usually rhyme or alliterate, and I didn’t really think about that much until I was an adult and writing poetry and thinking, “Oh, well, it’s really kind of fun the way that my grandmothers and my parents and my sister, how they just use language as this real kind of playful thing." And I think that might have something to do with the fact that I love to rhyme and use wordplay, just kind of listening to that growing up.

Jo Reed: Now, when did you become interested in poetry and actually writing the words down and doing written poetry as opposed to staying in an oral tradition?

Melissa Range: I love the sounds of things, but I really kind of have to write it down to understand what I’m thinking. I’m kind of a process-y person like that. You know, I always wanted to be a writer but I didn’t know I wanted to be a poet until I was in college. I think it’s because my schools where I went, we didn’t really do a lot of poetry. We mostly read novels, and so I read novels and I thought, "Well, maybe I’ll be a fiction writer." And so it wasn’t until college and I took this fiction workshop and I kept getting comments back on my stories that were, “Well, your language is really beautiful but your characters are flat and your plot makes no sense.” And I thought, "Well, I don’t really care about the characters or the plot. I just care about the language." But I hadn’t really thought that that equaled poetry. And then my junior year of college I took a workshop with a lovely poet named Marilyn Kallet, and after about a week I was like, Oh, I don’t have to have characters and plot." I mean you can have characters and plot in a poem but I don’t have to. It really can be all about what I want to do with language. And so then from that moment I was like, "Okay, I’m going to do poetry." And so I just started reading and writing and haven’t really stopped since then.

Jo Reed: I’m going to ask you to read another poem—I’d like you to read “Regionalism.”

Melissa Range: Oh, sure.

Jo Reed: Ties poverty to a certain extent together with region in that one fell swoop. <laughs>

Melissa Range: Yeah. This poem has a lot of little referential things going on, when you hear the line, “I don’t hate it but they all do,” is a repeating line in the poem. And I’m just kind of riffing off William Faulkner at the end of the novel “Absalom, Absalom!” And I'd also seen—you, know I love Natasha Trethewey, and I had seen her kind of riff off of this, too, in a poem in “Native Guard,” and so I was thinking about it. You know, I joke when I read this at readings. I’m like, “Okay, so people made fun of my accent my entire life and finally I got angry and wrote a villanelle about it to get my revenge.” <laughs> So that’s kind of what this poem comes out of, too.

"Regionalism. People mock the south wherever I pass through. It’s so racist, so backward, so NASCAR. I don’t hate it but they all do. As if they themselves marched out in blue they’re still us, them-ing it about the Civil War, mocking the south wherever it is. They’ve never passed through. It’s a formless, humid place with bad food except for barbecue. The grits, slick boiled peanuts, sweet tea thick as tar. I don’t hate it but they all do, though they love Otis Redding, Johnny Cash, The B-52’s. The rest of it can go ahead and char. People mock my southern mouth wherever I pass through, my every might, could have, and fixing to, my flattened vowels that make fire into far. I don’t hate how I talk, where I’m from, but they all do their best to make me. It’s their last yahoo in a yahooing world of smears, slur, and mar. People mock the south, its past. They’re never through. I’m damned if I don’t hate it and damned if I do.”

Jo Reed: 2015 was a big year for you: “Scriptorium” was chosen by Tracy K. Smith for the National Poetry Series.

Melissa Range: I couldn’t believe it. You know, poets, we always enter contests trying to win book prizes because that’s very often how a book will get published, and you never expect to win one. You’re just kind of throwing it in with a lot of other really talented people and just kind of keeping your fingers crossed that your manuscript will cross the desk of the right person. And I couldn’t believe that Tracy K. Smith picked my book. I mean obviously she’s such an incredible poet. And, it’s still just kind of flabbergasting to me. I really had to sit down when the people called me from the National Poetry Series, and I’m sure that happens to everyone who wins any kind of book prize. You’re like, “Are you sure you’re calling the right person?”

Jo Reed: That’s funny. And you also got a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 2015.

Melissa Range: Yeah, 2015 was my year of miracles, my boyfriend says, yeah, because I did. And I used that money to fund some research trips and some time off from my job and to work on my third collection, and I’m still working on it. I’m a very slow writer so I’ll be working on it for a while.

Jo Reed: And that leads to my final question: what you’re working on now.

Melissa Range: Yeah, I would love to talk about what I’m working on now because I’m so into it. And I just kind of innocently thought, “Well, I wonder if there’s any abolitionist poetry?" And then was there ever. There was so much abolitionist poetry, and I discovered all these wonderful poets like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who’s a great poet. And then as I kind of started reading more about them, I just started reading more about abolitionists in general and I was kind of stunned to see just how many people were involved in this movement, most of whose names we’ve forgotten, and I just decided I wanted to write poetry about these people. They did a lot of really good stuff in this country and they worked together even when they didn’t always get along, and they created this positive change and we should remember them. So I’ve been doing tons of archival research and trying to kind of make poems based on their text and their words. So I’m not trying to invent voices for them because they have voices, but I’m trying to kind of bring them back to our consciousness, I guess.

Jo Reed: And I look forward to reading it. Melissa, thank you.

Melissa Range: My pleasure. Thank you.

Jo Reed: That was poet and 2015 NEA Literature Fellow Melissa Range. We were talking about her collection of poetry Scriptorium. You can keep with her at MelissaRange.com. This is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed. Next up, we have an excerpt of my 2021 conversation with the former poet laureate of the United States, the brilliant Tracy K. Smith.

Tracy K. Smith is a writer of rare distinction…her work is lyrical, accessible and crucial—combining honesty, engagement and imagination as she explores issues of family, loss, race, history, desire, and the wonderous. Here is a small part of resume: she served as poet laureate of the United States from 2017 to 2019. She is the author of five prize-winning poetry collections, including Wade in the Water, Life on Mars which won the Pulitzer Prize, and most recently, Such Color. Her 2016 memoir Ordinary Light was a finalist for the National Book Award. In 2018, she curated an anthology called American Journal: Fifty Poems for Our Time—bringing together contemporary writers to create a literary sampling of 21st century America. There’s much much more, but I’m sure we’d all rather hear Tracy K. Smith read and talk about poetry…which was exactly where I began my conversation with her.

Jo Reed: Tracy, in your collection Wade in the Water, you have a long poem titled “I will tell you the truth about this; I will tell you all about it.” that’s derived exclusively from Civil War letters and deposition statements. Tell me how you came both to these documents and to the decision to use only those voices in the poem.

Tracy K. Smith: Well, I was invited along with maybe a dozen or more other poets many years ago now to write poems that were marking the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War and I mentioned the argument about was it or was it not about slavery. That’s always bothered me enough that I’ve often kind of distanced myself from conversations about the Civil War and the opportunity to write a poem in or toward that subject matter seemed important to take up. And so I thought what I would do was-- would be to research what black people alive at that time had to say about their own sense of what was at stake and I found two really wonderful sources that had a number of primary sources. The books were “Voices of Emancipation: Understanding Slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction Through the U.S. Pension Bureau Files” by Elizabeth Regosin and “Families and Freedom: A Documentary History of African American Kinship in the Civil War Era” by-- edited by Ira Berlin and Leslie R. Rowland, and so those books I thought were just going teach me and somehow enable me to metabolize all of this information, all of these different perspectives and write a poem in my own voice but of course what happened was I sat down and I was just copying down quotes, citing letters and building for myself a sense of what seemed like a kind of gospel version of this history, all these many different voices telling their versions of a single story and in some ways it is the single story of this country. And with all of those notes and these amazing resources it seemed senseless to try and do some sort of jujitsu on that and make it a poem in my own voice so what I chose to do instead was to just kind of curate a listening session to think about what people chose to say, how and to whom and with what hope in mind. That seemed like an important thing to ask other readers to pay attention to.

Jo Reed: In your work, history is often a shadow that shapes the present. It’s not as though the figure shapes the shadow; it’s the shadow shapes the figure. I wonder if you’d mind reading your poem “Declaration” and then telling us a bit about it.

Tracy K. Smith: Okay, yeah. “Declaration”:

He has

sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people

He has plundered our—

ravaged our—

destroyed the lives of our—

taking away our—

abolishing our most valuable—

and altering fundamentally the Forms of our—

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for

Redress in the most humble terms:

Our repeated

Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.

We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration

and settlement here.

—taken Captive

on the high Seas

to bear—

So that poem is obviously drawn from the text of the Declaration of Independence which I was reading as a way of trying to listen to history a little bit differently than I habitually had or maybe had even been taught to and trying to see if there was another story or another message within a document like the Declaration of Independence that could be useful to my understanding or even our collective experience of the twenty-first century. And what I found when I looked at it closely was that this narrative of the nature of black existence in this country leapt off the page, and I wrote that poem now maybe three or more years ago but reading it in 2021 after the summer that we’ve endured with so much violence against blacks and so much violence heaped on top of violence because of the fact of outcry and protest that poem is very haunting to me.

Jo Reed: yes. It does so speak to this moment and the nation at this moment is also struggling with its historical narratives, which is something that had to happen because if you’re sanitizing the past it’s like putting a Band-Aid on a festering wound. I’d like you to speak to how poetry can be key to opening up historical narratives since poetry, your poetry, insists on holding up and acknowledging not just various views but often contradictory views. It speaks with a multiplicity of voices.

Tracy K. Smith: Well, we’re drawn to poetry I believe because the most emphatic moments and experiences in our lives are often characterized by some sort of ambivalence. I know that motherhood is characterized by a simultaneous joy and a feeling of loss or fear or constraint, I think love is characterized by warring feelings and implications, and so poems help us take that apart; poems help us find language that illuminates those dualities or multiplicities that live within things that we think are supposed to be consistent, coherent and unified. What I think poetry does is it begins to make us brave enough to do that even when we’re looking up away from the pages of books. As somebody who writes poems as a way of making sense or finding clarity, I also understand that much of what we see is what we choose to see and unless we put pressure upon ourselves we could stop there and we could lose sight of so many other and perhaps truer details and realities or details and presences, and history seems like one of those things that you can get into a particular mind-set about and that mind-set can prevent you from being open to other versions of fact. What I like about poetry is that it asks us to listen in many different directions and to put pressure on our own impulses, our own assertions. The formal rigor of poetry urges us to think more rigorously about language and that I think urges us to think more inventively, rigorously and honestly about meaning. Poetry can be possibility-creating if we allow it to be.

Jo Reed: Your title poem, “Wade in the Water,” is such a beauty and that is a poem that picks a journey beginning in one place but really ending for me in a place that made perfect sense but was unexpected when I began the poem.

Tracy K. Smith: Shall I read the poem?

Jo Reed: Yes, please. I’d love to have you read it and then talk about it.

Tracy K. Smith: “Wade in the Water”

for the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters

One of the women greeted me.

I love you, she said. She didn't

Know me, but I believed her,

And a terrible new ache

Rolled over in my chest,

Like in a room where the drapes

Have been swept back. I love you,

I love you, as she continued

Down the hall past other strangers,

Each feeling pierced suddenly

By pillars of heavy light.

I love you, throughout

The performance, in every

Handclap, every stomp.

I love you in the rusted iron

Chains someone was made

To drag until love let them be

Unclasped and left empty

In the center of the ring.

I love you in the water

Where they pretended to wade,

Singing that old blood-deep song

That dragged us to those banks

And cast us in. I love you,

The angles of it scraping at

Each throat, shouldering past

The swirling dust motes

In those beams of light

That whatever we now knew

We could let ourselves feel, knew

To climb. O Woods—O Dogs—

O Tree—O Gun—O Girl, run—

O Miraculous Many Gone—

O Lord—O Lord—O Lord—

Is this love the trouble you promised?

Well, that poem marries an experience that I had that it’s kind of transparent in the poem. I went to a ring shout, I walked into the space, I was greeted by one of the performers who said, “I love you” and gave me a hug, and I was also in the midst of doing all kinds of research in the American South about antebellum history, and I was deeply troubled by what I knew I would find but, finding physical archives of enslaved existence and seeing plantations celebrated as though they were these destinations when in fact they were labor camps, that gesture of love transformed all of those feelings. It didn’t erase the fact of the past but it gave me another tool with which to live with it and I just needed to write the poem to go back into that space, that experience and slow it down, render something of it that might also invite a reader to see the beautiful life-enlarging choice that love is. And it’s not about everything is sweet and easy; it’s about we are here in the muck and the only way that we can get through to the other side, which is I think the very same mentality or understanding that had helped people survive slavery, is love.

Jo Reed: How do poems tend to begin for you, with an idea, with an image, with a sound?

Tracy K. Smith: Often it’s with a question or a preoccupation, something that makes me feel at least partly worried, and sometimes it’s love, the delight. Like I said, love is this wonderful thing but it’s so astounding because it somehow has power that isn’t yours and it’s-- it can be a reason to stop and think wow, what’s going on here? So for me it’s just the impulse to stop and say, “What’s going on here?” or “I don’t like where this is going” that leads me to the page. I rely on images because I need to be able to see myself in a place and in the presence of something in order to build a poem, and once I can see something images begin to take root and then I can feel myself almost engaging with them, being in physical proximity with them, and other capacities become easier for me to muster, sound, momentum. Form is often a tool that helps me keep going forward in a poem by setting parameters, and somehow all of those things if I’m working correctly create a momentum of their own whereby I’m no longer preoccupied with what I’m doing and I’m just moving forward into understanding or revelation.

Jo Reed: You were poet laureate from 2017 through 2019 and you focused a lot of that work on rural America. What inspired that?

Tracy K. Smith: Well, I got that phone call from Dr. Hayden at a time when it felt like America had cracked in half and I felt like speaking about our political situation in the vocabulary of politics was in some ways exacerbating that sense of division and I would often find myself thinking oh, if only we could talk to each other through poetry we would actually maybe listen better; we would understand that there are nuances that the language of political debate sort of eschews. And well, the opportunity to do something, to do a national-scale project, made me really want to return to that idea that maybe poetry could do this bridge building; maybe poetry could make us behave as our better selves when we are together with others. And since most of the work I’ve done as a writer has been in cities, in book festivals or college towns I thought maybe rural America would be a new context for thinking about all of the things that poems urge us to think about, which is everything, and what I found on that-- while I was on the road during those two years was that my theory was correct. <laughs> Poetry made strangers who probably had wildly different values and experiences confidants. I’d read a poem or I’d ask somebody else to read a poem by another poet and say, “What do you notice? What does this poem make you remember, feel, think, wonder?” and then we would just go places together. We would go to real places and vulnerable places and places where that feeling that I am like you in more ways than I’m inclined to assume that feeling kind of became present and I’m really grateful that I got to do it when I did. During this past summer, when everybody was on quarantine I often thought oh, gosh, this would be a great time to get back out there with poetry and see what we could help each other to ask and say and see.

Jo Reed: I’m going to ask you to read one more poem if you don’t mind. It’s a short one called “An Old Story.”

Tracy K. Smith: Oh, sure.

Jo Reed: I think that’s a nice place to end.

Tracy K. Smith: Yeah. It’s the last poem in “Wade in the Water” and the title for the next book is taken from this poem. I wrote it as an attempt to write a new myth for us in this country, something that allows us to look forward with courage and maybe a new sense of what the goals are.

“An Old Story”

We were made to understand it would be

Terrible. Every small want, every niggling urge,

Every hate swollen to a kind of epic wind.

Livid, the land, and ravaged, like a rageful

Dream. The worst in us having taken over

And broken the rest utterly down.

A long age

Passed. When at last we knew how little

Would survive us—how little we had mended

Or built that was not now lost—something

Large and old awoke. And then our singing

Brought on a different manner of weather.

Then animals long believed gone crept down

From trees. We took new stock of one another.

We wept to be reminded of such color.

Jo Reed: That is a wonderful place to leave it. Tracy, thank you so much for giving me your time.

Tracy K. Smith: It’s been a real joy. Thank you.

Jo Reed: That was the former poet laureate of the United States, Tracy K. Smith, her latest collection of poems is called ”Such Color.” Her other books include, Wade in the Water, Life on Mars, and her memoir Ordinary Light. You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us on Apple podcasts or Google Play and leave us a rating, it helps people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed, stay safe and thanks for listening.

This week, the podcast is divided into two parts with one subject—poetry. Part 1 is excerpts from my 2018 interview with poet Melissa Range. Her collection Scriptorium mingles history with the personal as Range explores how language is used and abused—who speaks with authority? Whose language is dismissed? What do we preserve and how? From medieval illuminations to Appalachian slang, Range discusses the joy and creativity that’s found in the vernacular. Scriptorium was chosen for the 2015 National Poetry Series by my second guest Tracy K. Smith who also wrote the foreword to the book.

Part 2 of the pod excerpts my 2021 interview with 2017-2019 US Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith. Today’s podcast focuses on her collection Wade in the Water a wide-ranging series of poems that reflect on history and contemporary America. Smith looks at both with an unflinching eye that mixes compassion and outrage with her lyricism and attention to language. Smith’s work sings to us of possibility while demanding an acknowledgment of what was and is. Again, we are compelled to grapple with: Whose voices are heard? What is preserved? Smith discusses the power of poetry to open up historical narratives and complicate contemporary assumptions by speaking intentionally with a multiplicity of voices.