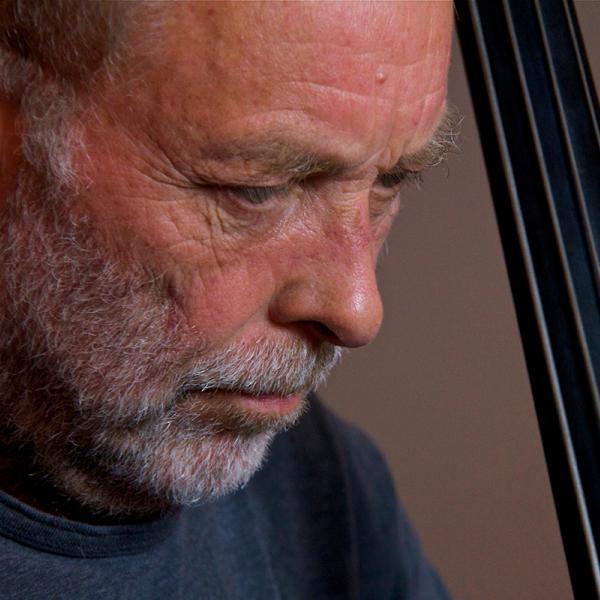

Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro

Photo courtesy of Max Roach Film.

Music Credit: “NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of Free Music Archive

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, This is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed.

Today we commemorate the centenary of 1984 NEA Jazz Master Max Roach, -- a titan in the world of jazz and pioneering cultural activist. To mark the occasion I spoke with two esteemed filmmakers, Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro, who have co-directed the timely documentary "Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes." Let me tell you a bit about the filmmakers: Ben Shapiro, a drummer himself, has extensive background in both film and radio documentary and notably as a long-time producer for National Public Radio. Sam Pollard is a multi-award winner, editing, producing, and directing films about the African American experience, such as "Eyes on the Prize II" or “when the Levees Broke”—you may remember him from my 2015 conversation with him about his documentary August Wilson: The Ground On Which I Stand. Both Sam and Ben bring their seasoned perspective on storytelling and cultural documentation to Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes. In this centenary year of Max Roach, join us for this deep dive into the life of a musician who not only revolutionized music but also stood as a powerful voice for social change. And that is where I began my conversation with Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro—by asking them to place Max Roach in American music and as a political advocate. Here’s Sam Pollard

Sam Pollard: I think Max Roach is an icon in 20th century American music, first as a drummer, then as a composer. And then as a person who was able to bring into his orbit some phenomenal musicians from Clifford Brown, to Booker Little, to Dee Dee Bridgewater, to Charles Tolliver, to Stanley Cowell, Gary Bartz, phenomenal musicians. So I think he is in the pantheon of great American musicians. That's how I would describe him. And in terms of Black consciousness, he became a major hero of mine because his notion of the importance of not just being a jazz musician, so-called, but being someone whose music was about engaging and challenging the American status quo of racism. He stood head and shoulders among us being a musician who felt that he didn't just want to entertain, he wanted to be an activist, and he wanted to be involved in challenging what it meant to be an American, and what it meant to be an African American in this country.

Jo Reed: Thank you. Ben?

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, I think Sam put it well. I mean, the only thing I might add is kind of more specifically in terms of as a drummer, I think, I mean, clearly, as Sam said, he was a central figure in 20th century American music. But even more particularly, if you look at drumming, and the history of drumming, he was one of those very rare examples… I mean, it's hard to think of other examples of instrumentalists on any instrument who have had such a singular impact just on how the instrument is used, how the instrument is played, and so I think that's something that's worth emphasizing. In terms of Black consciousness, when we were making the film, we were very aware, too, of the relationship of Max's work as an activist— as an activist artist as it relates to social movements of today, and I think we saw him also as a role model in that regard also, even for our current time. So even though we can look at him as a historical figure, the way he applied his art, the way he expressed his concerns around social movements in his art, remains a model today, I think.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I would agree. I mean, his politics are as much of today as his music is. Sam, how did this film begin with you? I know you, both of you, have had a long life with this film. So how did this film begin with you?

Sam Pollard: Back in 1983, I was editing the documentary about the poet Langston Hughes and the director of that film, the late St. Clair Bourne, he did a sequence where Max Roach was performing a drum solo to one of Langston's poemsAnd I cut that sequence and I said to St. afterward, "Man, Max Roach is phenomenal. Somebody should make a film about Max," and he turned to me and said, "Man, you should." And I was stunned. I said, "Me? I never directed before. I'm just an editor." But he said, "Man, you should make a film about Roach." So he paired me with our associate producer on that film, a woman named Dolores Elliott and he introduced us to Max, and we pitched the idea to Max, and he was on board with it. And then we raised some money. And in 1986, '87, we shot our first session with Max, a long interview at his apartment on Central Park West, 100th Street and Central Park West. And then a few days later, a week later, I don't remember now exactly, we shot a session with him doing a rehearsal session with his group, M'Boom, his percussion ensemble. Then we were able to raise some money from his record label, and we went to Milan, Italy, where he was doing a concert with the Woodwind and String Ensemble. And then I cut material together, and I looked at the cut after about, I guess it was 1988, '89, and I thought it was horrible, absolutely horrible. and the big mistake was I showed it to Max, and he sort of didn't say yay or nay, and that sort of really stumped me, and I put it away. I would take it out every few years, look at it, make changes, look at it, hate it, put it away. Shoot some additional interviews, put them in, look at it, put it away, and almost 20 years went by, and then Ben Shapiro, who I knew, you know, we got together one day, and he said, "Man, let me see this footage you got of Max," because he had been a drummer-- and I'll let him tell you that part of the story.

Jo Reed: Okay, take it away, Ben.

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, well, when I was a teenager, I got interested in learning how to play the drums, and I was actually very lucky that I got to take lessons with a guy named Craig Woodson, who was at that point giving drum lessons to support his work. He was studying to get a PhD in ethnomusicology, but he was studying drums, and drummers, and drumming, and doing transcripts of Max Roach, and Tony Williams, and all these people. And he introduced me to drummers, but he always said that Max was the seminal figure, that's how important Max was. And so that stayed with me, and then I also, the more I learned about Max Roach, the more I also learned about his composing, the different bands he did, the “Freedom Now Suite”, the other music in the '60s, and so I just recognized that he was a fascinating and important figure. I've always had a kind of dual career where I work in film documentary, film and television, and also in radio. I produce for National Public Radio. And around 1989, when, unbeknownst to me, Sam was filming Max, I managed to get a project going doing a half-hour audio documentary for NPR about Max. And I went to his apartment, and he was very generous with his time, and we spent hours, probably about five, six hours over the course of two days recording these long audio interviews, -- basically he told me his life story. And so I produced this program and put that material away and held on to it, and then when I heard that, you know, Sam and I became friends later, and I knew that he had worked on his film, and I suggested we combine our material, and then we started working on completing this film.

Jo Reed: So for both of you, how did your individual filmmaking styles and experiences sort of complement each other in the making of this documentary? What were you each bringing to the table as you put this film together? And Ben, I'll throw it back to you, and then to you, Sam.

Ben Shapiro: It was a very complementary co-directing relationship. I've done that before, but, you know, we worked well together, and I'll see if Sam agrees. I think we both felt similarly about what the film needed to cover, what it needed to be, and we just kind of brought our own focus to it. I was the cinematographer for the interviews. I mean, that was helpful, I think, in terms of the film, getting it started, you know, before we had raised any money. We were able to do some of the important interviews, because I owned the equipment, and we just kind of went out and did them. But yeah, we just both applied our interests and focused on making the film that we thought we should make.

Jo Reed: Okay, Sam, and what about for you?

Sam Pollard: I have to say that Mr. Shapiro and I, I'm in complete agreement with him, we got along really well. It was very collaborative. We would get together every week at a little coffee shop. We'd get together and talk about who should we interview, put together a list of names. Should we go to the Smithsonian to get this material? When do you have time? You know, who's going to be this person that we're interviewing? And except for maybe two or three interviews, we did them together. As Ben said, he shot and did sound, and I usually did the interviews, and it worked out well. I mean, we, I think one of our first interviews was with Sonny Rollins.

Ben Shapiro: It was, yeah.

Sam Pollard: Yeah, Sonny Rollins and then we went on and did Dee Dee Bridgewater in New Orleans, and we did Jimmy Heath in Queens, and we did Randy Weston in Brooklyn. Ben went out to California and did Daryl Roach, one of Max's children. Then we did the other children here in New York together. So it was a really easy collaboration. And in the editing process, we had a wonderful editor, Russell Green, and he might have felt a little challenged because he's had to deal with two directors, but I don't think we didn't beat him up too badly.(laughs) So I think it was a great collaboration, and I have to tell, I'm very proud of this film. I mean, every time I see it and I don't watch, you know, I don't watch my stuff as much as I've been watching this one. I'm very proud of it, and I'm excited that it really has captured people, and people have really sort of taken to it.

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, I think that's an important point, though. I think we both were so excited just about doing it, and we went to the Library of Congress and looked through the archives there. That was just exciting, and like, we're eager to find things and so, that was part of it, too, just our enthusiasm. But I also want to add, I mean, when you get to work with Sam Pollard: I always feel like that's a great opportunity. He's so experienced, and so sophisticated in his understanding of the process of making films, and that I knew, I always knew, when we were working on the film together, that I could rely on his input in terms of process, in terms of what the film was like. So I always felt like that was a gift for me. So I always welcomed that as part of the situation of making the film.

Jo Reed: Well, I want to talk about the process of making the film, because you had a lot of archival material going into it. But then, as you said, you did any number of interviews. And that's my question, because Max Roach had a mighty reach. I am fortunate enough to be able to speak with a lot of great, great jazz musicians and I can tell you, I always expect at least one of the following three names to be cited as their greatest influences. The organization AACM, Art Blakey, or Max Roach--- profound influences, not only about their impact on them as musicians, but as people. So how did you select the interviewees for the documentary?

Sam Pollard: So we wanted to make sure that we found musicians who knew Max, or performed with Max, or was in his orbit, and that was important. We had this discussion a lot. Should we have scholars, jazz historians, talking about Max and bebop in the 50s, that period in the 60s? But as we've talked more and more, we knew we wanted to have musicians who knew Max, you know, who understood who Max Roach was. So that led us to people like Randy Weston, who grew up with Max in Brooklyn, that led us to Jimmy Heath, who performed with Max in the 50s. That led us to Tootie Heath, who was a drummer. That led us to Dee Dee Bridgewater, who had performed with Max. So we were pretty aware that it had to be musicians, because to me, it would make it more intimate and more personal. I guess the only musical historian we talked to for the film, and I think he did know Max, was Greg Tate, the late Greg Tate, which was great. And then we threw in Questlove, because he was a drummer, and he had loved Max growing up. So but most of people we interviewed were personal musicians who knew Max personally.

Ben Shapiro: Greg Tate was also at a couple of his key performances, right? So he could talk about seeing him directly, and being at some historic moments in his career. So yeah, pretty much everybody in the movie talks about things that they experienced firsthand, which, as Sam said, was something we felt was important.

Jo Reed: Well, there is so much to Max Roach, his life as a musician, as a person, as an activist, it's so hard to get your arms around. But you make it clear from the first frame that you were going to explore and present him both as an artist and as a political figure. So we knew this is what it was going to be going in. Walk me through that decision, and how that ended up framing the film, which I think it did.

Sam Pollard: Well, we went around and around on how to open this film. I mean, we had a bunch of different versions about opening this film. One of the versions, we opened up with Max passing away. The sequence at the very end with Maya Angelou. Another version, we opened with Max-- we used the excerpt from “Freedom Now Suite”. We had a lot of different versions, but we always knew that it was important at the very beginning, as we started to go through these different editing iterations, that we put up front that Max was not just a jazz musician. He was an activist. He was a person who was about doing more than just entertaining. So that was really important for us to do that as we were shaping the story. So like all filmmaking, it was a back and forth in the process. I mean, another shot that's at the end with Max, has got his drumstick up and he comes down and he starts playing his drum solo. That was another opening. I think we had like six or seven openings before we decided on this one, it wasn't easy. And the other big thing that we did that we hadn't even considered initially was that introduction with me and Ben at the Library of Congress, going through the archive with my voiceover. And Michael Cantor, the executive producer of American Masters, had seen an earlier version without that, and he had suggested, you guys should really give them a sense of the history of this project, the context. And initially, Ben and I were reluctant, because I don't really like to put myself in these documentaries. But then as we talked about over and over and over again, we decided, "Okay, let's try it." And we had shot the footage at the Library of Congress because of just that. Ben had brought the camera and said, maybe we will never know if we'll use it, but let's shoot it. And we shot it. It turned out to be invaluable.

Jo Reed: Yeah, that was surprising, breaking the fourth wall. That's very unusual for you, Sam.

Sam Pollard: I know. I rarely do it. But this time, I think it works.

Jo Reed: Yeah, I think it does too. Ben?

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, I mean, I think we both felt that we wanted to do a full biography of someone. I mean, a lot of jazz historiography and jazz music histories are about: this person played this, and they played that, and then the next person took to the next musical level, they did this. But we really wanted to do a full portrait of Max as a human being, as a musician, as an activist, and that was kind of our focus. So that was one of the reasons why we made that particular choice, to really give him the fullest dimension.

Jo Reed: Well, he was one of the creators of Bebop, playing with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, but maybe because he was a drummer, not really given the props that others get. Talk about his role as a drummer and how he changed, not just drumming, but the way we think about drumming, and the sounds drums can produce. And I'll throw that to you, Ben, first, since you're the drummer.

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, I guess I'd answer that in certain ways. Certainly, you can look at the development of-- as you mentioned, with that group of musicians in the 1940s, that developed this music that was called Bebop or modern jazz. Max played a key part in that, developing that, and also a key part in shifting the way the drums were played at that point from the way that they had been played previously, like in the 1930s. I mean, one of the big things was moving the timekeeping element to playing rhythm on a cymbal, on a ride cymbal. He was one of the drummers that was important in doing that. But I think there's something larger about him, which is he had this vision, as he talks about in the movie, that you could look at drumming and percussion as being involved with the world of sound. In which case, drumming and percussion becomes kind of limitless. It can be on a wide range of instruments. It can be using instruments different ways, and so I think that kind of sense of open possibility was something else that he contributed that was very important in drumming. And also, I mean, obviously, we can see that played out in his career over the course of all the different explorations he did. I mean, he not only said that, he was a model of doing that by this constant musical reinvention and exploration through all these different musical forms over the course of five, six decades.

Jo Reed: Sam, do you want to add anything?

Sam Pollard: Ben said it all. I mean, listen, here was a time when drummers in the 30s, they were playing basically on the bass drum to keep the time. And along comes the Max Roach and the Kenny Clark, and they used the ride cymbal to keep the time. And that immediately lifted this level of the drumming and tempo of the drumming for groups with Charlie Parker and Dizzy and Al Haig and all these musicians who were a part of that bebop movement. But then, the thing about Max that makes him so special is that every decade, he was evolving as a drummer. He wasn't just going to be a drummer that kept time. So when he started his own group in the 50s, the seminal group with Harold Land and Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, and then switching over from Harold to Sonny Rollins, that was another change musically in terms of Max. And then in the late 50s, early 50s, he decides that the drum should not just be a timekeeping instrument, it should be a soloist, which it was, but he became a soloist, where he knew that he could go on a stage just with his drum kit and create a whole set of musical performances without anyone else. And that sort of took him into a whole new direction, and Ben's right, his notion was about developing sound. Drums as a place to, you know, enrich this notion of musical sound, which he did. And one of the reasons that he brought together M'Boom was to bring together all these beautiful percussionists, not just drummers, who could play a variety of percussion instruments to create different textures and moods and feelings just on percussion instruments. Phenomenal. And then he moves on and he creates what's called the double quartet, where he has his daughter and these other string players, cello and violin, and viola, playing alongside his quartet, which had Cecil Bridgewater or Billy Harper. So he was always thinking ahead, and then he's doing duos with Cecil Taylor or Archie Shep or Dula Ibrahim or even with Dizzy Gillespie. This guy was never sitting, resting, on his laurels, which makes him such a special, special percussionist.

Jo Reed: One collaboration that you do focus on in the film is Max's partnership with Clifford Brown, who's a brilliant, brilliant musician, died way too young and is too little known. Can you explain who he was in Max's life and something about the depth of that collaboration? Because it's so important and the music they created is still phenomenal, phenomenal music.

Ben Shapiro: One thing that I think was important about Max's collaboration with Clifford Brown was that it was really the first time, I think, that Max was able to articulate his vision about how a group would sound. And of course, that involved bringing the drums more up front. The drums play a central role in that band in a way that maybe even in earlier bands, the drums weren't so up front, weren't so central that way. But also, I mean, look, Clifford Brown--- you really have to look at someone like that and recognize that he was a supremely gifted musician, the kind that comes along a few times in a century, really, on a particular instrument. And he still recognized as such, even though he died when he was just 26. And so having someone like that to help articulate Max's vision, someone who shared his level of proficiency and genius, and to be able to collaborate closely with someone like that. I mean, my sense is from listening to the recordings, and from the way he talked about it, it was a unique and special collaboration.

Sam Pollard: Yeah, I would just add that, you know, listen to those compositions. I mean, these guys were at the top of their musical game. There was a range of musical expertise and subtlety that they brought to each composition they played on those albums and then, they had a wonderful tenor player in Howard Land, and then even a greater tenor player when Sonny came on. They are phenomenal musicians and you're right, that you can still listen to this music, and it feels very contemporary, it feels very strong, even now. What can you say about Clifford Brown and Max Roach? That group will live way beyond Mr. Shapiro and Mr. Pollard.

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, I know. That's an interesting point, too, about these works that don't age, works that are timeless. And it's a very special category, it's rare, but you sure can recognize it when you hear it, you know, and we could go down the list, and we could talk about it. What are the other examples of that? But this certainly is one.

Jo Reed: How did Clifford Brown's tragic death affect Max both personally and professionally?

Sam Pollard: Well, obviously, as we say in the film, it was devastating for Max to have the loss of Clifford Brown. It's just absolutely devastating. And he went into, as his family says, he went into a dark hole for a number of years. But he was able to regroup on a musical level, and he put together some very interesting bands. I mean, his Deeds Not Words band, with Ray Draper and George Coleman, it was a pretty damn good band. I mean, and the bands he had with, Booker Little was a member of them, it was great. He had different groups, he was always out there. I mean, Ronnie Matthews was playing with him for a bit. So he kept playing and performing, even when he was going through all this sort of psychological and emotional turmoil on a personal level. And remember, by early 60s, he did the “Freedom Now Suite”, which was seminal. I mean, he met Abby Lincoln, they fell in love, and she was a phenomenal performer herself, and then to collaborate on the “Freedom Now Suite”, whoa, brother, that's like, when you just watch that footage, I still get chills. Watching Max with Clifford Jordan, I think it's Coleridge Perkinson's on piano, it's just fantastic to listen to these musicians play that music. And that music is revolutionary; every composition--the hairs on the back of my neck, they rise every time I listen to it.

Jo Reed: I wonder if you can talk about how the “Freedom Now Suite” was conceived, and also the impact it had, not just on the music world, but on the movement, both here and in South Africa.

Ben Shapiro: Well, my understanding is “Freedom Now Suite” was actually originally commissioned by the NAACP, and it was initially performed at a conference, I believe. But I mean, Max had, by that time, already made the decision that all of his music was going to be connected to the civil rights movement, for movement for social change, and so he brought that sense to this work. Abdullah Ibrahim talks in the movie about the impact of the Freedom Now Suite and Max's music of the 60s on the movement there, and activism there, and how much it was an inspiration to him, and to others in South Africa. That they knew that someone like Max Roach was paying attention to their struggle, and that was very important to them. And that was also recognized by the South African regime at the time, so the record was banned, and other records American musicians that had the word freedom in the title were banned at the same time.

Jo Reed: I'd love to have you talk just a little bit more about Abbey Lincoln and the significance of Max's marriage to Abbey, because she was a significant artist in her own right, with her own artistic vision. How do you see their careers intersecting and influencing one another?

Sam Pollard: Well, he meets Abbey in the mid-50s, the mid to late 50s, and she was then, a classic sort of slash jazz pop singer. And she was being set up to become sort of a pop diva, sort of something in sort of the same kind of ilk as Nancy Wilson did later on in her career. And Max met her and told her, "You don't have to do that." You don't have to be just a sort of this pop singer with these tight-fitting dresses. You have more talent than that. And she's an amazing performer. I mean, she was not only a wonderful, wonderful singer, but she was a phenomenal actor. I remember seeing her in Nothing But a Man in 1964, She was a very talented lady. As I was trying to get people to interview for this film, I reached out to Abby. I reached out to Abby in 1988 or '87. I took her out to dinner, to try to persuade her to do an interview about Max, and she turned me down, and I was probably just excited that she said yes to me taking her to dinner. She was a great, great musician, great musician. Listen to her singing “Driver Man” on “Freedom Now Suite”. Listen to her during the “Tears for Johannesburg” or “Freedom Day.” She had the chops to do some great stuff musically, which she did.

Jo Reed: Max, meanwhile, is having some issues getting work because he didn't just want to play music. He wanted to put his music into a context. He talked to the audience about where it came from, and promoters did not like it. That had a fairly significant impact on his career, didn't it? And I'll throw that to you, Ben.

Ben Shapiro: Well, it did. I mean, he was very committed to his politics, towards presenting certain things to audiences that he felt like they needed to hear and in some ways, that put him at odds with club owners and presenters who wanted them to be just entertaining audiences, as they put it. And we should recognize that also impacted his recording career. He was recording for major labels in the mid-60s into the late 60s. He was on Atlantic for a while, and they dropped him after he started, you know, kind of focusing on this music that had these particular themes that were connected to the civil rights movement and movements for social change in the 60s. And so it definitely had an impact on him and his career. He mentions in the film, even his ability to make a living was challenged. So I think that was difficult for him. At that point, he was able to get a teaching job at UMass Amherst and moved his family there, which enabled him to keep on doing the work that he's interested in doing without compromise.

Jo Reed: Yeah, that was a very interesting, perhaps unexpected side note that happened when he went to Amherst, because he also found an artistic community there and other musicians and students and faculty that he could play with--have his ongoing band. The way Charles Mingus did, or Duke Ellington did, that it could happen at Amherst.

Sam Pollard: Well, that was sort of the icing on the cake for Max. I mean, here he was, a renowned musician was having trouble finding work in the clubs, but he was able to go teach at Amherst and bring up some younger musicians, but also keep a working band off and on to do guest appearances. So he was still productive, but he wasn't making the money that he had been making when he was just doing the club scene. But I think, being a former professor myself, in some ways I would assume-- and I would think that experience also invigorated Max, both, you know, musically. He put together vocal ensembles, he had percussion ensembles. I think it was also a good place for him to be, because it kept him sharp, it kept his ears open and kept him wanting to connect with other musicians, younger musicians.

Jo Reed: “The Drum Also Waltzes” has been widely praised. It premiered at South by Southwest—and played in festivals not just in the US but around the world. It is part of PBS’s American Masters series and was aired in October.

And 2024 is Max's centenary, so I imagine the film is still going strong and we’ll be seeing it in theaters, community centers, libraries across the country. I know it’s showing in the Newark Museum of Art on January 18 followed by a panel discussion and you both will be taking part in it

Sam Pollard: We're going to be in Newark, and. I think there's a screening of it going to be at Black Public Media in April.

Ben Shapiro: Yeah, there's going to be the Library of Congress, as you know, it's going to be at the Pan-African Film Festival, LA in February and the Vancouver, and screening at the Hot Docs Theater in Canada, also in February. And it's going to be in Spain And also now it's also available as a rental on Amazon and on Apple TV.

Jo Reed: But this is the kind of film that it's certainly fine to see on your own, but honestly I think is just begging to be seen, as part of a community event.

Ben Shapiro: Oh, exactly.

Jo Reed: Yeah, to open up discussion, you know?

Sam Pollard: I agree. I mean, that's why I'm looking forward to the screening in Newark. I screened it at a festival here in the summer and there was a really great reaction to it. I agree completely. It's a wonderful film to see with an audience. And people come up to me after the film and say, "Man, I remember hearing Max at this place or Max in that place," and it's just such a treasure to be able to share this film with so many people.

Jo Reed: And that's my final question, it is Max's centenary, and I think the film plays a really important part of the story of Max Roach and I wonder what you're hoping audiences will take away from “The Drum Also Waltzes”. And I'll go to you first, Ben, and then you, Sam.

Ben Shapiro: It's kind of a hard question for me because I think of him as such a multi-faceted character, and such a rich life in so many ways. I guess the one thing-- well, several things. One is just the richness of his musical life over the course of his life, I hope people come away with that understanding. Just what an extraordinary artist he was. And I think people recognize Max Roach or have often recognized him in kind of fragments, in a funny way, I think there are people who are drummers who recognize certain things he's done on the drums, there are people who look at the Freedom Now Suite and that's very important to them. There are people who look at M'Boom, and his later-- But I think it's important to be able to look at him as the entirety of his career and so I think that's what I'd like to take away from him. And also, I mean, it sounds kind of funny to say, but I'd like people to recognize him as a person. It's very easy, often with great artists and jazz musicians, they're mythologized in a certain way, and I guess I'd like the people in seeing this story that we've created as an arc of his life, kind of feel like they kind of understand him as a person, get to know him as an individual. You know, kind of empathize with the track of his life overall.

Jo Reed: And Sam?

Sam Pollard: What I would say is this, the important thing to take away from this film is that if you are a human being, no matter if you're a musician, or a doctor or a janitor, you should stay open to the curiosities of life. And never sort of lock yourself into just doing one thing or being one way. Stay curious, stay open, stay engaged and that to me is why Max Roach is such a major, major hero for me, because he was always engaged. He was always curious, and as I said earlier in this interview, he never rested on his laurels. And that to me says all it can say about a human being like Maxwell Lemuel Roach..

Jo Reed: And I think that is a great way to end this. Sam, Ben, thank you both so much. Thank you for making this absolutely terrific film.

Sam Pollard: Our pleasure.

Ben Shapiro: Thank you.

Sam Pollard: Thank you. Be good.

Jo Reed: Thank you. You just heard from filmmakers Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro—we were talking about their documentary Max Roach:The Drum Also Waltzes. To keep up with showings of the film, check out the website Maxroachfilm.com. And if you’re in the New Jersey area, on January 18 the film is being screened at Newark Museum of Art where the filmmakers will take part in a panel discussion and then on January 26 NJPAC is presenting a performance of Max Roach’s “Freedom Now Suite” we’ll have a link it all in our show notes.

You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple. It helps other people who love the arts to find us. We’d love to know your thoughts, email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine reed. Thanks for listening.

In today’s podcast, filmmakers Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro discuss their film Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes. In our conversation, they place Max Roach within the context of American culture, emphasizing his legendary status as a drummer, a composer, and a significant figure in Black consciousness and activism. Pollard shares his 40-year journey in making this documentary, while Shapiro talks about his own connection to Roach, reaching back to a radio documentary.

They discuss their coming together and collaboration in making the film, highlighting their complementary skills. We talk about Roach's musical evolution from a seminal drummer in the bebop era to a soloist and a leader in exploring new dimensions in percussion; the profound impact of Roach's collaboration with Clifford Brown, especially in terms of musical innovation; the toll Brown’s early tragic death had on Roach; and the film's focus on Roach's "Freedom Now Suite" and its significance in both the music world and social movements, including its impact on the civil rights movement in the USA and anti-apartheid struggles in South Africa. We also discuss Roach's marriage to Abbey Lincoln, noting her influence on his life and music, and her own significant artistic contributions, as well as how Roach's political activism impacted his music career and his transition into teaching, where he continued to influence younger musicians. We also discuss upcoming screenings of the film and upcoming events celebrating Max Roach’s centenary. Overall, the interview paints a comprehensive picture of Max Roach's life, his immense contributions to music and social activism, and the journey of creating a documentary that captures his multifaceted legacy.

We’d love to know your thoughts--email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. And follow us on Apple Podcasts!