“I think the arts are one of the things that make us human.” — John Jacob

As the U.S. approached 1976—its bicentennial year—the NEA started to think about how it might celebrate the occasion through the arts. One of the pilot projects commissioned by the Arts Endowment in 1974 comprised a documentary photo series of the state of Kansas modeled on the work undertaken by an earlier generation of photographers working for the Farm Services Administration (FSA). The Kansas project was helmed by photographer and photography curator James L. Enyeart, who along with fellow Kansan photographer Terry Evans and Larry Schwarm, spent roughly a month shooting in the state’s many small towns and rural areas. Through July 31, photographs from this project are on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in

No Mountains in the Way: Photographs from the Kansas Documentary Survey, 1974, an exhibit celebrating the 40th anniversary of the commission.

Following the success of the work in Kansas, as noted in the SAAM exhibition text, “From 1976 to 1981, the agency awarded Documentary Survey grants to more than 100 regional photographers… [which] documented communities across the United States, from Appalachia and Galveston to Syracuse and Cheyenne.”

We spoke with SAAM's McEvoy Family Curator for Photography John Jacob about the initial genesis of the project, the importance of the NEA to the field of photography, and how the documentary survey project was both a nod to the past and an enthusiastic homage to the then-present.

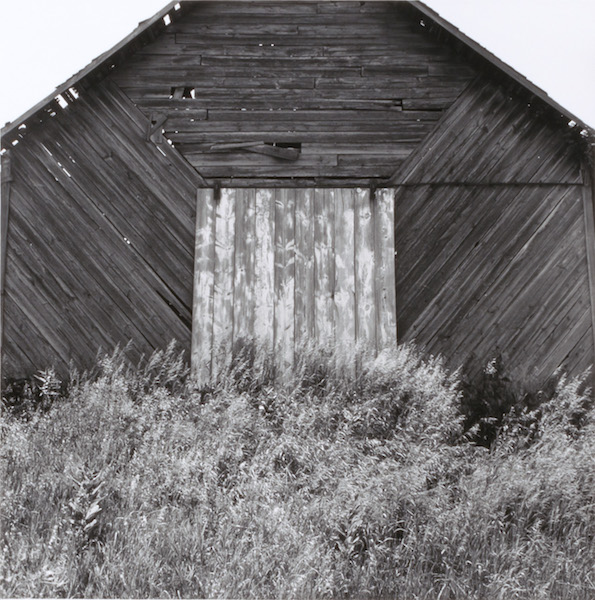

Terry Evans, Untitled, from the Kansas Documentary Survey Project. 1974. Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts. ©1974, Terry Evans

NEA: These photographs were taken as part of a documentary survey. What does that term mean?

Terry Evans, Untitled, from the Kansas Documentary Survey Project. 1974. Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts. ©1974, Terry Evans

NEA: These photographs were taken as part of a documentary survey. What does that term mean?

JOHN JACOB: During the bicentennial year the NEA began to give a series of grants to do surveys, and it had many meanings, but in general what it meant was that one or more photographers would write a proposal to the Arts Endowment and ask for funds to survey a community, whether a small town or a large city. So there were surveys done across the country, and most of those projects, like this one, were contemporary, funding photographers to work right [at that time]. But other surveys were to work inside of historical societies, for example, with their photography collections to bring those collections to a bigger public, to preserve them, to conserve them, and to exhibit them.

NEA: What can you tell us about the survey project in general, which I know was a precursor to a much larger documentary project?

JACOB: The importance of this exhibition in terms of the whole survey project is that this is the first. Before the American bicentennial, [then-U.S. Senator] Walter Mondale and Congress had a meeting to talk about the possibility of doing some big photographic project like the Farm Security had done, [which would be] great documentation during the bicentennial year. Congress eventually approved it, but the funding never became available, and the NEA took it over at that point. One of the photographers who spoke before Congress [on behalf of the project] was Jim Enyeart, who is the curator of this exhibition and one of the photographers. He was adamant that this kind of thing should be done and that sort of American government support had a tradition, but that if it was done it shouldn't be done politically, that artists should be able to work on their own.

For me, within the field of photography [the documentary surveys are] one of the great successes of the Arts Endowment. It's an enormous and an enormously important body of images made from across the country. Our collection's over 7,000 photographs, and of that about 3,000 came from the NEA. The first piece of our photographic collection was a transfer from the NEA, and… probably about 1,000 were survey photographs. This is probably only maybe half of what was created… Many of these photographers are little-known today, but quite a few of them went on to prominent careers, and the NEA's support of photographers at this time, including this five-year period, was really, really important.

NEA: Can you tell me about the photographers who were involved in the Kansas part of the project?

JACOB: Jim Enyeart did a really interesting thing with each of the photographers [on the Kansas project]. Jim wanted to photograph the architecture, and he was working in the style of Walker Evans, who was one of the Farm Service Administration photographers. He brought in Larry Schwarm and Terry Evans. Larry liked to photograph people, and Terry liked to photograph the landscape, so just to make things interesting, [Jim] asked Larry to photograph the landscape and asked Terry to photograph people. So they were in a place that was familiar to them because they all lived in Kansas, but each was doing something that they were a little bit uncomfortable with.... Larry is a funny person and a funny photographer, and his irony comes through in these photographs. Terry's photographs of the landscape are very neutral and broad, and her photographs are a little bit standoffish. Her photographs of people in this series are a little bit standoffish. Jim's photographs… are probably the most neutral of all. They are facades, and there's almost no evidence of life in them. You see signs, you see flags waving, and you see shadows of children, but there are no people in them. Jim's thought was that—as for the Farm Services Administration—if he assigned each photographer to take on a certain subject that the three topics brought together would combine into something, the sum of which would be greater than its parts.

I think Jim Enyeart's intention with this was to enable three artistically inclined photographers to go into a place and do exactly what each wanted to do. He gave the instructions, "You do people, you do this," but at the same time he didn't give them any more instruction than that. There was no shooting script like there was with the Farm Security Administration. I think he wanted the results to look unplanned, and in that way it would be a neutral document for visitors years later.

I've looked at [the exhibit] with people from Kansas. Some of them are critical of it: It doesn't have many city scenes, and there are certainly urban centers in Kansas. But others feel that it captured something that would be called characteristic of Kansas, at that time especially. So I think somebody viewing it today might find that sort of aura or nostalgia about it, but I think it's a pure document. They came in, they worked fairly quickly, they each did what they wanted to do within a narrow period of time, and it represents that exact moment, which is what photography does best in a way.

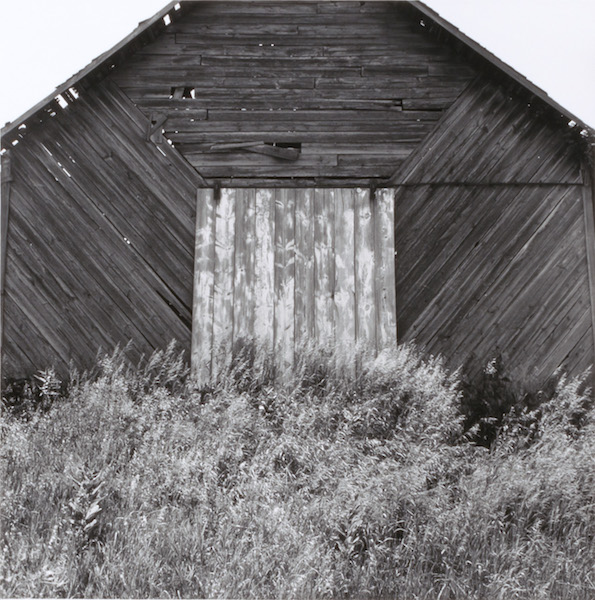

Larry W. Schwarm, Barn, Jackson County, from the Kansas Documentary Survey Project, 1974. Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts. © 1974, Larry W. Schwarm

NEA: Are there any images that you think are particularly significant or that are your favorites?

Larry W. Schwarm, Barn, Jackson County, from the Kansas Documentary Survey Project, 1974. Transfer from the National Endowment for the Arts. © 1974, Larry W. Schwarm

NEA: Are there any images that you think are particularly significant or that are your favorites?

JACOB: I didn't know Larry's work before, and he's a favorite of our museum's director because she's also from Kansas, and so she's worked with him over the years—as I think she has with all three, in fact. In part because I didn't know this work, I've loved looking at it, getting to know it, and the humor of it is very appealing to me. Terry Evans' work is more intimate. She's photographing people, and at the same time, if you look at them, she's at a distance. There's nothing that's too close, and so it's very much in the documentary tradition of kind of a neutral distance…. Jim Enyeart's photographs are, again, I think the most classic. I think he was using Walker Evans as a model, and I think he wanted this body of images to look backwards specifically to the FSA that was his inspiration, so I think that's what this group of images does. They're photographs that [are similar to] what Walker Evans would've done, like this one with the car, but I think in general using that model it really looks backwards, and so you have the present very much in the whole show but sort of a visual pull to the past.

NEA: Are there photographers out there that are doing this type of work now that you think people should look at or that you find particularly interesting?

JACOB: Maybe it's due to our troubled times that photography is addressing human issues again or is being used to address human issues again, so, yes, I think there's actually quite a lot of that kind of work being done now. It’s very easy to find it online; there are so many different photography Web sites and Web magazines and blogs.

NEA: Do you think the ubiquity of photography now, the fact that I could flip this phone around and take a photo of you right now, has changed the way we relate to photography as an art form?

JACOB: I think that if you look at art museums now as compared to when I was younger, they are so much more crowded…. They are popular places. If you go to a city you often go to a museum, and I think that the omnipresence of photography contributes to that, to our comfort or increasing comfort with the visual. I think people are interested in looking and people are also interested in making, and photography is one of the simplest tools that you can do both of those things with. Then [there is] the opportunity to go to a museum and look at masters who used the same medium and to learn from that or enjoy it just pleasurably.

NEA: How do you describe the power of photography? What is taking photographs of Kansas bringing out about the state in a way that’s different than writing about it or making a movie?

JACOB: What's unique to photography among all art forms is we know that this happened. There are some photographers who are great masters of the form and the technique, but for the audience, we're looking at a piece of history. With a photograph of a person we're looking at the light reflected that day from that person onto the plate, onto the negative. There is a reality to this kind of photography that is different from any other kind of artmaking, and I think that that facticity of it is fascinating.

NEA: My final question: Why do you think the arts are so important to us?

JACOB:

I think the arts are one of the things that make us human. The arts slow us down and ask us to look at them or to read them, and when I read something, reading fills me with something else. It gets inside, and so does an image, so does looking at pictures or sculpture, and that I think is part of what makes us human, that transfer of experience by which we learn.