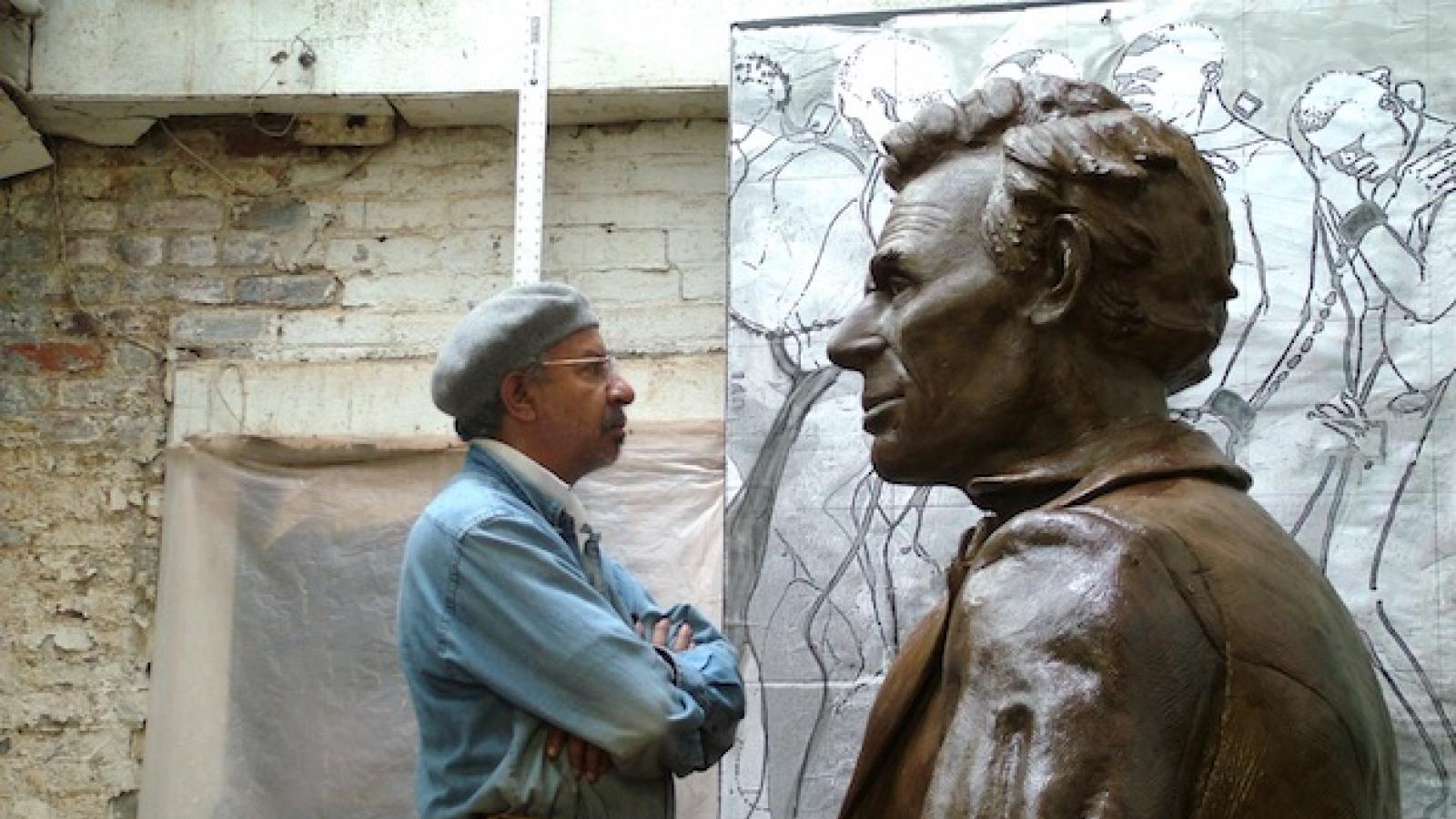

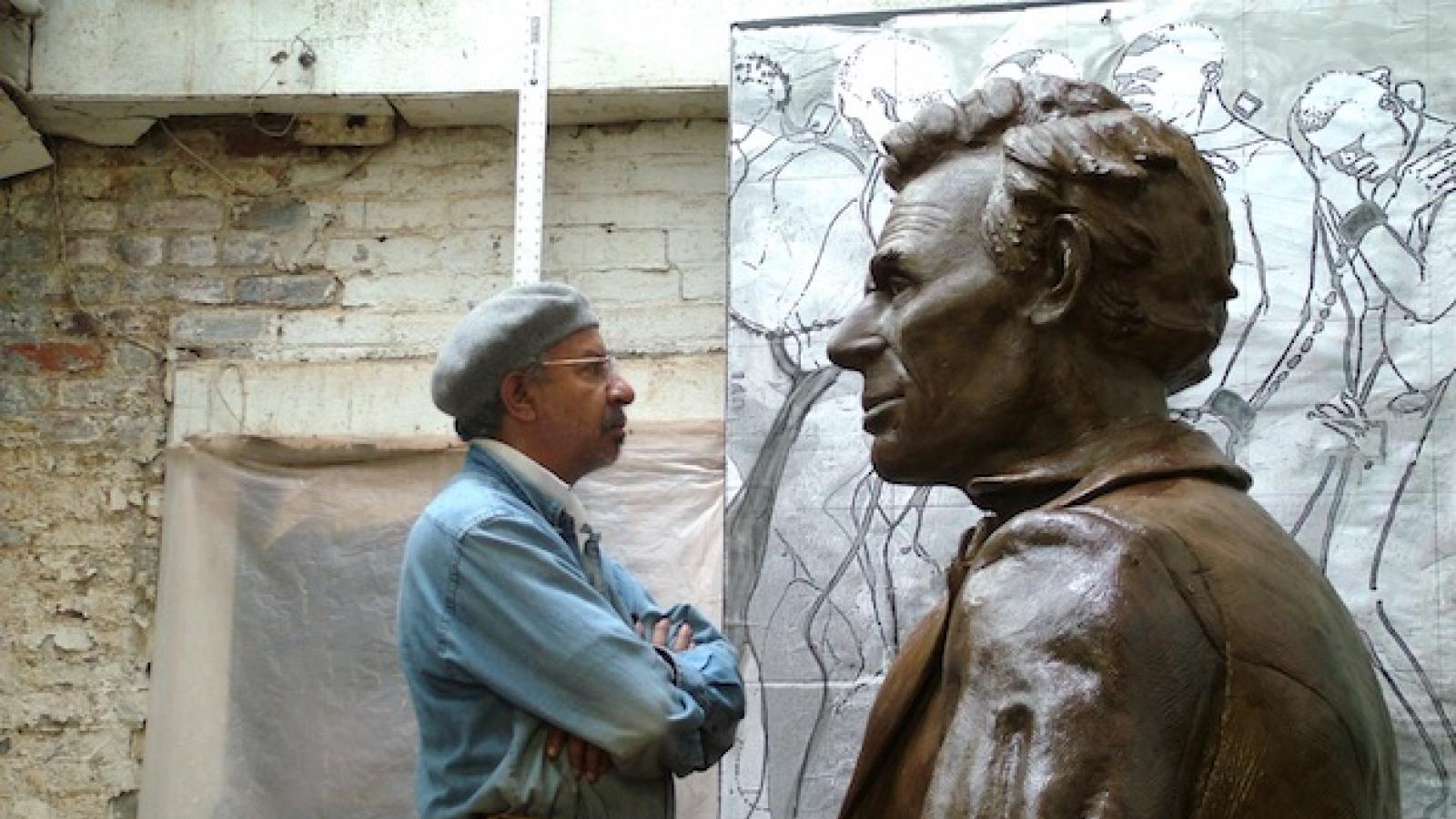

“Memorials need to address issues. [They] need to address honoring certain people, events, and they also need to tell you about a particular time period. Whether you like it or not, they should provoke a new way of thinking about a subject.” — Ed Hamilton

Sculptor

Ed Hamilton has been fascinated by three-dimensional objects ever since he was a young boy. Growing up in his parent's combination barber and tailor shop, Hamilton would scavenge buttons, tin cans, shears—whatever he could find laying around to build his very first designs. This interest in crafting blossomed in high school when Hamilton was introduced to working with clay, which led him to study sculpting at the University of Louisville. Like most artists, Hamilton fantasized about having his own gallery that showcased his works. But a chance encounter with sculptor Barney Bright in Louisville, Kentucky, in the late 1970s changed the trajectory of Hamilton’s profession. Apprenticing with Bright for eight years taught him what he needed to know about making public artworks. So when Hamilton was asked to do his first major commission—a sculpture of Booker T. Washington—in 1983, he was eager and ready. Now, with a career spanning over 30 years, Hamilton has made such important works including

The Spirit of Freedom in Washington, DC, La Amistad Memorial in New Haven, Connecticut, and The York Memorial in Louisville, Kentucky. “It's like all of a sudden I’ve become a historian,” he said when we chatted with him. “I wasn’t a historian in the beginning; I was just an artist wanting to be a sculptor. I feel so honored to be able to create memorials.” Here is Hamilton on his affinity for three-dimensional objects, how he got his start as a sculptor, and the impact creating memorials has had not only on his life but the lives of others.

NEA: Can you tell me about your origin story as an artist?

ED HAMILTON: As a child, I grew up in downtown Louisville [,Kentucky] in the heart of a black community in the black business district. My dad was a tailor, and my mom was a barber, and so I grew up in a barber/tailor shop combination. That meant that there was a wealth of stuff around me at all times—my dad’s sewing stuff and my mom's haircutting tools. I would make my own creations out of 3D things. I was always in my dad’s button box, and he’d get mad at me, saying “Get out of my box, boy.” And my mom would follow suit saying, “Stop using my scissors and my shears for cutting tin cans.” I got into trouble quite often, but I couldn’t help myself; I always wanted to explore. I would walk along Walnut Street, where my parents’ shop was located, and there were liquor stores, boutiques, grocery markets, and in the store windows, I could see plaster busts that piqued my interest. For some reason, there was something about the physicality of the building and the plaster figure; it was an affinity I felt for 3D objects.

In high school you learn how to draw first, then you learn how to paint, and then you learn how to work with clay. I was able to manipulate clay better than some of my classmates. My high school teacher knew I should go to art school. So I got my portfolio together and included a clay piece, three paintings, and my sketchbook, and with that, I got a four-year ride to art school at the University of Louisville. Once I got to art school, I realized there was something about the sculpture studio that really drew me in. In my second year of college, I had to take sculpting, and that year in that room is where I just found myself. Once I got into the sculpting department, I never left.

NEA: Who were your inspirations as a sculptor?

HAMILTON: I met a major sculptor here in Louisville [in the 1970s] and worked with him for about eight years as his apprentice. His name was Barney Bright, and he made public monuments in Louisville and the surrounding region. So, I learned about the making of public art through him, and I wanted to do what he did. At the time, I was teaching sculpture and ceramics at a public high school in Louisville, and I went to the ceramics shop next to his studio on Franklin Avenue to buy clay for my classes. I knew that Bright’s studio was right next door to the shop because I had studied his work over a period of time and I’d always wanted to meet him. Anyway, I loaded up the car with the materials, and I was parked right in front of Bright’s studio. Something told me, “Get of out the car, and go knock on the door.” Well, I just couldn’t. As I was turning the key in the ignition to start my car, he walked out his front door to check his mail, and I thought, “Uh-oh this is it!” I got out of the car, walked over, introduced myself and mustered up the courage to ask Mr. Bright if I could see his studio. He said, “Sure, come on in.” When I crossed the threshold of his studio, that’s when my life changed.

NEA: What was the first memorial sculpture that put you on the map as an artist?

HAMILTON: My major breakthrough came in 1983 when a call came to create a public monument for Booker T. Washington at Hampton Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. I wasn’t doing that type of work at the time, so the commissioners didn’t know anything about me. Luckily, I had a friend, his name was Kenneth Victor Young, who worked as a museum proprietor and is an artist and tailor for the Smithsonian Institute in DC. It just so happened that he knew the museum curator in Hampton and they ran into each other at [a museum] conference. She asked him, “Hey Ken, do you know anybody we could contact to do a Booker T. Washington memorial?” And Ken said, “Yeah, my boy Ed Hamilton in Louisville.

It took a year to do. They wanted a heroic figure. I went through the archives and found various pictures of him talking outside. I found a picture where he was talking and pointing, and that was the pose I used for the sculpture. I created a bust and submitted a photo, and the committee said, “Hey he can do this.” A year later I get a letter in the mail for a Joe Louis commission in Detroit.

NEA: What’s your process for creating a memorial sculpture?

HAMILTON: I spend a lot of time doing research even before I put pencil to paper. I go to the local library and start digging and finding out as much as I can about the person or event. Once I fill myself up with some knowledge about the subject, that’s when I start thinking, “Okay, now how do I put this in context of where it's going to go?” Because for the memorial sculptures, I work with a committee and coordinate with landscape and design architects so that my work complements what they do. It’s a lot of time spent on research, reading, initial sketches, small-site model-making. After I start on an actual scale model to present to the committee for approval, then I make an actual large version in clay. Once I’m finished with the large version, my job is pretty much over at that point, other than just waiting for the foundry to turn it into a bronze piece.

NEA: What kind of insights do you gain for the design of the sculpture from the historical research?

HAMILTON: For the

Spirit of Freedom in Washington, DC, I found a wonderful book called

Colored Soldiers by William Gladstone. He did a historical photo book on actual photos of [African-American] soldiers back during the Civil War era. So that book allowed me to be able to see actuality from that time period. I didn’t want to do any one specific person, but I used my imagination and was able to create these figures on the sculpture. Sometimes you work from life; if you’ve got a person that’s alive. Or [if] they’re deceased, you can work off of a photograph, like [I did with] Booker T. But dealing with the aspects of these soldiers who were long gone, I just had to use my imagination to create the figures I wanted. The memorial features three uniformed soldiers and a sailor on the front and on the back [there is] a young family.

NEA: Memorials are generally works of public art. Why do you think it’s essential that this kind of art exists in the public square?

HAMILTON: Memorials need to address issues. [They] need to address honoring certain people, events, and they also need to tell you about a particular time period. Whether you like it or not, they should provoke a new way of thinking about a subject. I like it when the public looks at one of my pieces because they may take away something different because I’m too close. I’m thinking like a learned person, and sometimes too much learning can be a bad omen.

NEA: How have creating these memorials affected your life?

HAMILTON: They’ve had a profound effect on me. However, I think they’ve had more of an impact on others, and that’s the beauty of this whole thing. I know my legacy is now set—there’s no question. I realize that I’m creating something that viewers may not have known about historically. It's like all of a sudden I’ve become a historian. I wasn’t a historian in the beginning; I was just an artist wanting to be a sculptor. I feel so blessed to be able to create memorials. I feel honored.

NEA: What do you hope people take away from viewing the memorials you created?

HAMILTON: I think the main thing is that they see I’ve done the best job I could. They step away saying, “Oh, this is great. This is so powerful.” I want them to see how I took a subject and was able to tell a story through my piece. Also, its so important for my people, African Americans, to be able to see people that look like them in the public space. To give you an example, when the DC memorial was unveiled, there was a young black boy circling the piece and a white woman watching him, firmly grasping her purse. The young boy kept looking and looking at it, and all the while she’s watching him. Finally, he came around the front side where she was standing and said to her, “That looks like me.” You don’t see a lot of memorials that portray African Americans. It’s only been within the last 30 years maybe that we started to actually create memorials in honor of people who’ve done things for the civil rights era. Ultimately, I hope that they take away that I’ve done the best I could do, that I’ve honored their legacy, and honored their people.