Grant Spotlight: At the Intersection of Theater and Trauma with Everett: Company, Stage and School

According to Aaron Jungels, co-artistic director of Everett: Company, Stage and School, a 1996 study showed that more than two-thirds of the population has experienced an adverse childhood experience, with 20 percent having experienced three or more of these traumatic events. For many young people, those incidents result in post-traumatic stress. Everett, which has served the Providence, Rhode Island community for more than 30 years by providing free access to performing arts training, received a National Endowment for the Arts grant in the latest round of funding to support the creation and production of Good Grief, a multidisciplinary theater piece created to help participating artists and audiences heal from PTSD. We spoke with Jungels via e-mail about the devising process for the work, how the arts can help the healing process, and the importance of NEA funding to the success of Everett's mission.

NEA: Tell me, in your own words, about the work of Everett Stage. If you had to write a job description for what the company does, what would it say?

AARON JUNGELS: Everett is an artist-run organization first and foremost. It’s a group of people who need to express themselves through dance, theater, and film. That’s what gives life meaning for us and it’s at the core of what we do. Added to that is a deep understanding of the powerful role the arts can play in society. The arts draw our communities together, they tell our stories, they question power, they elicit our emotions, they strive for justice and equity, and they inspire us to imagine new possibilities.

We provide employment opportunities for young developing artists so that they can see the arts as a career. We train them to teach; we develop arts-based educational programs with them that address issues of concern to the community and then they go into the schools and carry them out. The students relate to our artists because they look like them, they grew up in the same neighborhoods and have faced similar situations.

The stage is where these young artists cut their teeth, it’s where they discover the magical connection between performer and audience. Most of our students don’t even know what theater is when they first come to us, they’ve never been on a stage, and then they fall in love with it, and that’s a beautiful thing to see.

NEA: What sparked the idea for Good Grief? How was it developed?

JUNGELS: One of the things you often hear about with mass incarceration is the school-to-prison-pipeline, [which is] when challenging students are pushed out of schools and into the criminal justice system. Over 70 percent of students who don’t finish high school end up justice involved. Well, many of those students with behavioral issues in school, who are dealt with in a punitive manner, are exhibiting symptoms of untreated PTSD. So, it’s like we’re punishing them for being traumatized.

Everett was brought in to infuse the arts into a clinical program in middle schools, to make it more engaging for students. It was a group therapy program for students who screened positive for PTSD. So, we used performance and role play and it was very successful; engagement went through the roof. But the amount of trauma that we saw in the schools was mind blowing. It’s an epidemic, which isn’t surprising to people who have been paying attention. But a lot of people aren’t, and a lot of schools are just in denial about it. Their way of dealing with it is to expel students. So as a company we decided that trauma should be the next subject we tackled.

All of our company members are former Everett students and they all have trauma in their pasts. So it ended up becoming a very personal piece about trying to find out how you heal from trauma. As the director my first concern was to not do any harm to the performers. So we brought a therapist named David Medeiros into the process as a collaborator. He practiced something called the Internal Family Systems model of psychotherapy or IFS.

IFS is an intuitive model that views a person as having three categories of parts—exiles, managers, and firefighters. Each part has valuable qualities and wants to play a positive role within. Often our parts are forced out of their valuable roles by life experiences that reorganize the system in unhealthy ways. IFS is non-pathologizing. It recognizes that, at our core, we have a true self undamaged by our experience, that can heal our parts and bring harmony back to our internal system.

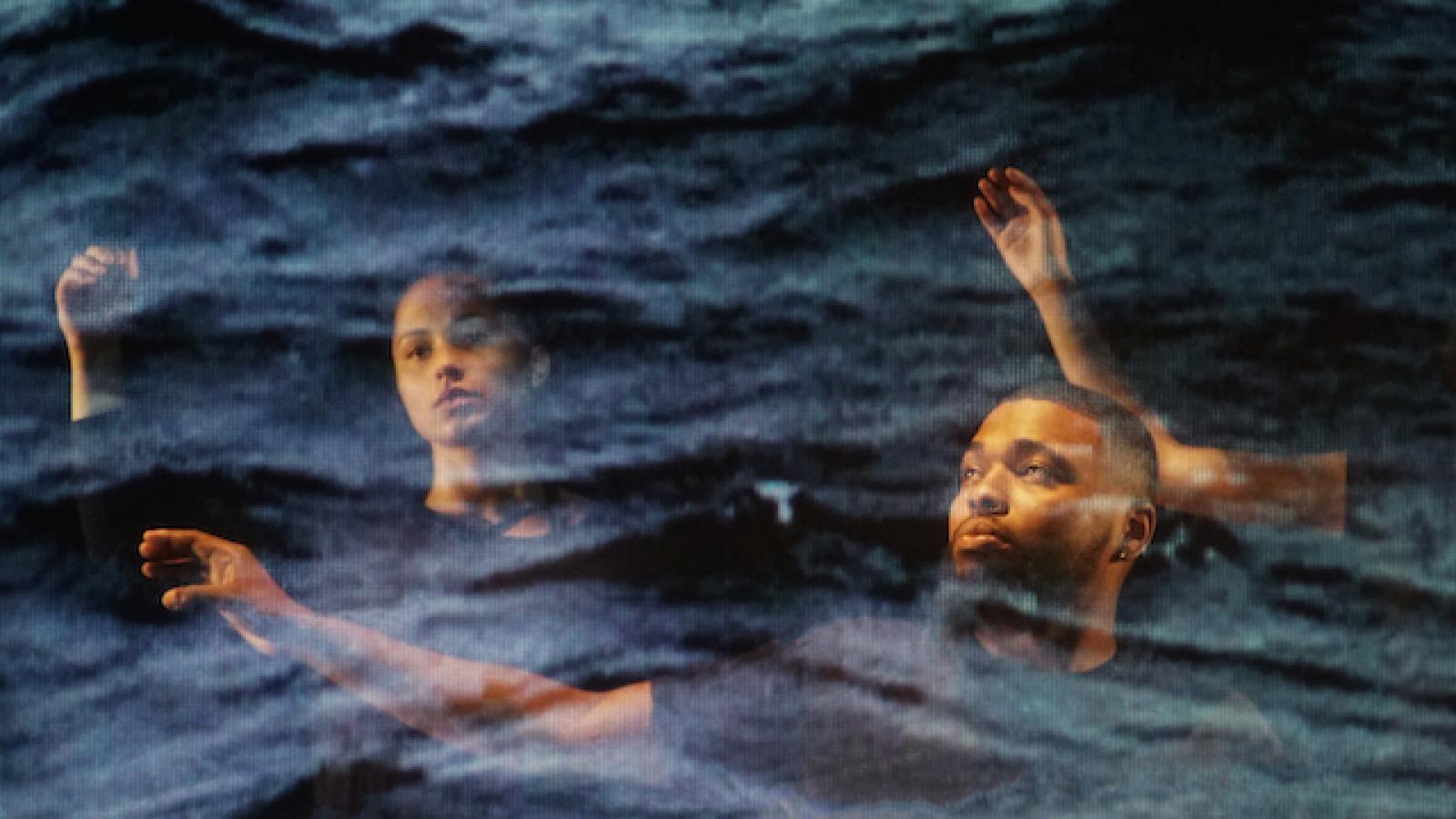

IFS quickly became a key to how we could really show the healing process onstage. In rehearsals, David would work with one of the performers while the rest of us watched, and we would video tape everything. Those sessions became the basis for scenes, dances, and multimedia stage-images. IFS gave us a way to access and draw out the inner world of the performers in a safe and healing way. But none of it would have been possible without their courage, and trust in each other and the process.

NEA: What are the benefits of tackling an issue like mental health via the arts?

JUNGELS: One of the things they say about trauma is that you can’t really talk your way out of it. Healing can’t just happen in a cognitive manner; it has to involve the body. Well, dancing and acting are all about being embodied. So in a way performance was the perfect modality to explore trauma. You can still have that intellectual piece through words but you can also hit that visceral part through the movement and the emotions.

NEA: What do you want the audience to take away from engaging with Good Grief? What about the performers and other participants?

JUNGELS: When we were in the creation process, I always felt that if the performers experienced some level of healing within themselves, then we would have something worthwhile to share with audiences. In the discussion periods after each show all of the performers have talked about how healing the process has been and how they have been changed by the work. I’m not saying that all of their issues are fixed, but they’ve started on a road and they are committed to continuing down it. Many of them are seeing IFS therapists on their own now.

This has also translated to audiences. Many have talked about how much it meant to them to see the artists be so vulnerable and open onstage. Many said that it made them feel like they aren’t alone in what they struggle with. It has been gratifying to see Good Grief’s impact on audience members from a wide-range of ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic backgrounds. At one performance we had a group who were just out of prison and one man connected deeply with [one of the character's] interactions with his angry self. The man said he had struggled all his life with his own anger and was just beginning the process of getting to know what that was really about.

NEA: How does a work like Good Grief benefit the public in general?

JUNGELS: There was a study done on adverse childhood experiences (ACE) back in1996 called the ACE study, which found that two-thirds of the population have experienced at least one ACE in their lifetime. Twenty percent of the population have experienced three or more ACEs. So, there are a lot of people out there who have experienced trauma; Good Grief acknowledges this fact. It raises awareness that [post-traumatic stress] is not just something experienced by soldiers; it is all around us in our communities. It reduces the stigma many feel around speaking openly about their experiences of trauma. It reduces stigma related to seeking help with our mental health needs. It offers hope that there are ways to heal. And best of all, it does all of this through an emotionally engaging and compelling arts experience.

NEA: Why is National Endowment for the Arts funding important to this work?

JUNGELS: The arts have been under attack in our society for decades. They’ve been removed from public schools. Often they’re been priced out of the reach of the average person. No one wants their child to be an artist because it isn’t seen as a viable career. But the NEA has been there throughout this long downturn. Despite the many political attacks and attempts to defund it the NEA has withstood and remains a beacon. It shows that as a society we really do value the arts.

The fact that the NEA funds work like this validates it. It says that it’s important that art is available to everyone despite their economic status. That the arts can make a difference in people’s lives and be a positive force for change in our society. Even though the grants are not huge, the NEA often provides the first seed money for a new project. This allows new ideas and new artists to flourish and grow and find their audiences. A show like Good Grief that deals with a topic that many would prefer to ignore is a perfect example of the power of the NEA to lift up and champion a challenging work of art. And it turns out that there is a lot to be gained by challenging ourselves.