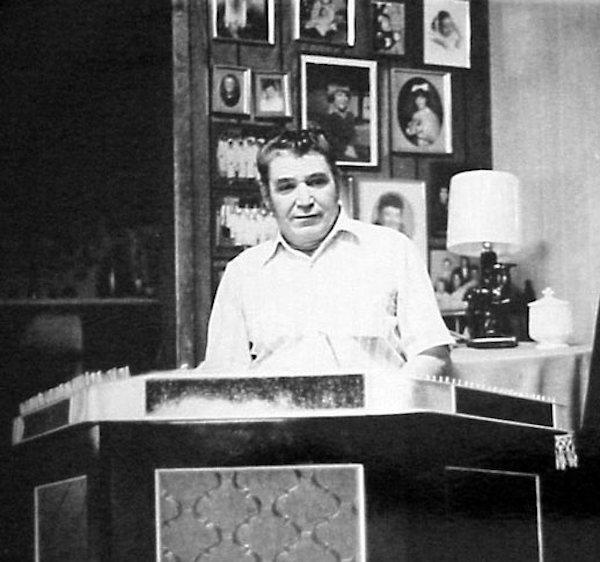

Albert Fahlbusch

Photo courtesy Albert Fahlbusch

Bio

Albert Fahlbusch was born April 18, 1925, in Scottsbluff, Nebraska, near his grandfather's farm. His parents, Molly and Herman Fahlbusch, were German immigrants who had come to America around 1920. When Albert was four years old, his father died. His mother later married a man named Jake Zitterkopf. As a child, Albert got interested in music by listening to his stepfather's records. "We had some records when I was about seven years old," he said, "and they had dulcimer on them, but I didn't know what it was. They just called the instrument the board."

When Fahlbusch was about 15 years old, he saw a guitar in a second-hand shop and bought it for two dollars. "I didn't have all the money," he said, "and they let me buy it if I paid them 25 cents a month. Well, I didn't know how to play or tune it. Finally, someone I knew was able to tune up the strings and I went right back home, but I still couldn't play anything on it. But I practiced on it to where I could play a few songs." After a while, a local accordion player, Rudy Temple, invited him to join his polka group. On the first night, another member of the band was playing the board and Fahlbusch realized that the sound was from those records he liked as a child. It was a hammered dulcimer, an instrument he had never seen before.

The hammered dulcimer is a trapezoid-shaped instrument of the zither family. It is played by tapping the metal strings with a pair of soft hammers. The performer usually sits in front of the instrument, which sits on a table or stand. This ancient instrument is known from China to England. It was brought to Nebraska primarily by German and Russian immigrants who enjoyed its delicate melodic line and particularly relished it as an accompaniment for their Dutch Hop polka style. This style is still popular with their descendants.

Fahlbusch began playing the hammered dulcimer in 1952. "I bought one from Jake Haun," he recalled, "but he didn't want to sell it to me right away. Finally, after a while, he asked me if I still wanted one and he let me get it. I didn't know how to play it. My brother-in-law had an accordion, and he helped me tune it."

Having no teacher or written music, Fahlbusch taught himself by sounding notes on his guitar, then finding them on the dulcimer. A few years later, he decided to make an instrument. Drawing on his mechanical and woodworking abilities, he quickly became known for the beauty and excellence of his instruments. He has sold a few to music lovers but seldom makes them with the intention of selling them. Rather, he hopes "to make each one better than the last." He continually experiments to improve the tonal quality and intends the instruments to be played, not looked upon as art objects. "Usually I had them on hand, and somebody came along and wanted one," he said. "And I only sold the ones I didn't like as much. I kept the best ones for me."

To support his family, Fahlbusch worked most of his adult life as a cement truck driver, playing music and building instruments in his spare time. He once bought and tore down old pianos to get wood with the proper tonal quality. Once those instruments attained antique status, he could no longer afford them, and finding good wood became a problem. He buys hardwood, primarily maple. Each dulcimer involves about 200 hours of work. He spends an additional 20 hours making the mallets. "You probably wouldn't have to be that particular," he said. "You could make them in an hour, if you wanted to. I like them to look nice and to balance nice."

Fahlbusch has been invited to festivals across the country. He has accepted some of these invitations and has served as a performer and teacher at University of Nebraska festivals. But his principal musical activity is playing in a polka band for dances, weddings, and other celebrations of the German and Russian communities of western Nebraska. Since his retirement in 1997, Fahlbusch has continued building hammered dulcimers, but has also pursued other interests. "The one I'm working on now, I started in 1971 and I kept getting new ideas. I've built 35 dulcimers so far. And I want each one to be a little better. I'm always learning something new. I haven't played a dulcimer for about a year. I've had cancer and it's too heavy for me to carry by myself. But I've got a violin, and I'm teaching myself, just like I did with guitar and dulcimer. I just amuse myself with it."