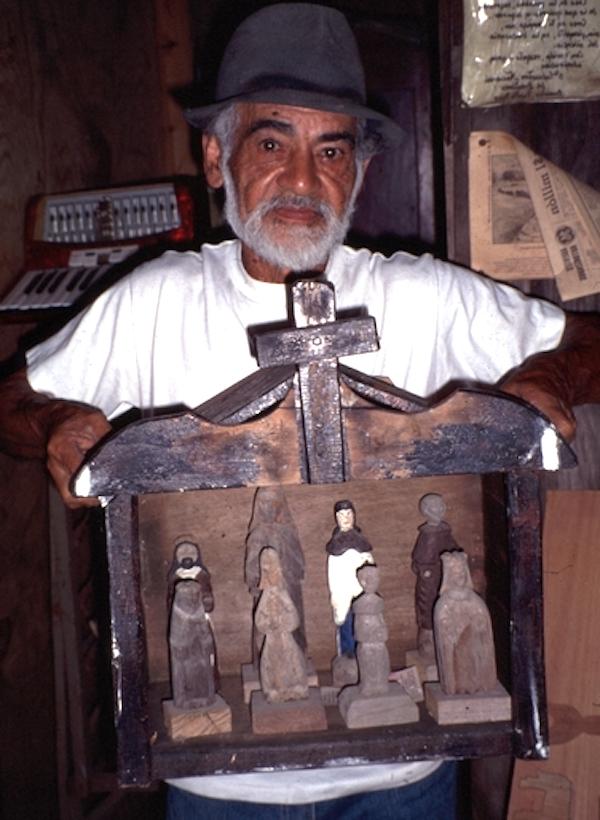

Celestino Avilés

Courtesy of the artist

Bio

Celestino Avilés lives in Orocovis, the hilly central region of Puerto Rico that is the geographic heart of the island. His artistic genre, the carving of wooden santos (saints), is acknowledged to be at the spiritual heart of Puerto Rican cultural identity. The carving of saints dates to the early period of the Spanish conquest. Farmers in the isolated mountains of the island carved saints out of local woods, such as cedar, developing their own indigenous aesthetic. It is largely due to the efforts of Celestino Avilés that the craft of saint-carving has remained a vibrant tradition in his homeland. Avilés began carving rings of corozo, the nut of a prickly palm tree, when he was a child. Later, while selling his rings at craft fairs he began to study with master santeros (saint carvers) Norberto Cedeño and Juan Cartagena. Soon Avilés became known for his skilled carving of saint figures, choosing to leave them unpainted and depicting them with closed eyes, in "a position of absolute religious solemnity" as he puts it. In 1982 he founded the Museo Orocoveno, known locally as the Museo de la Familia Avilés, in order to preserve the history of saint-carving in the region. A year later he initiated the Encuentro Nacional de Santeros (National Gathering of Saint Carvers) on the grounds of the museum. As Walter Murray Chiesa, craft specialist in Puerto Rico says, "Today Celestino Avilés is considered by many a Puerto Rican legend: a true living monument, a great carver of wood, bone, stone, sea shells and a leader: a natural born Ôinitiator' of great enterprises and projects. He is unique, very modest and a true symbol of our folk artists." Thanks largely to the inspiring work of people like Celestino Avilés, today the tradition of saint-carving is enjoying a renaissance in Puerto Rico, with over 100 carvers actively working in a wide variety of artistic styles.

Interview with Carlos Arrien

[Editor's note: the interview was conducted in Spanish and translated by Mr. Arrien. The interview is also available in Spanish.]

NEA: What does Santero mean and is that the right word to use to describe someone who is dedicated to your craft?

Celestino Avilés: Some time ago we used to see more Santeros, the people who carve saints. Churches used to be dispersed over long distances, so they resorted to asking anyone with skills in the surrounding community to make them. Some of them had good results, in the artistic sense, while others would come to the churches to observe the work. That's how Santeros got started.

NEA: How did you become a Santero?

Avilés: When I was a boy I used to go to Juanito Cartagena's barber shop to get my hair cut. I used to admire the carvings of saints he would set out to dry in his showcase. He was my godfather and was one of the best carvers of his time. I looked at his work in detail, but did not start carving until much later, on the advice of a friend. At first I worked with "corozo," the seed of a palm tree that is extremely hard. I taught my children how to make rings and all sorts of charms from the corozo, because times were hard and we need the income. A friend of mine by the name of Norberto Cede–o, one of the old carvers, persuaded me to start carving. I did and soon after the first products came from my hands. I taught myself how to do it. But he remained as my first influence. So much so that, later, I got together a committee to name a cultural center after him, here in Orocovis. I think it is unique on the island.

NEA: What contribution does the Santero make to the cultural heritage of Puerto Rico?

Avilés: I think it is the first craft of Puerto Rico. It is the first thing the tourists ask for when they arrive here. I think this sets us apart from other countries. This tradition dates back three to four hundred years. The families here in Orocovis and Morovis, they are all carvers. It seems we have it in our blood. We have a festival that gathers the Santeros from throughout the island every December. We gather here the third week of December and it is the biggest activity for Santeros. We even have a small museum, here in Orocvis, which we put together, because we still don't have any help from anybody. Lots of people come to see it, even from abroad.

Celestino Avilé talks about his work

Celestino Avilé talks about his work

NEA: What were the biggest obstacles for Santeros and what is the hardest thing today?

Avilés: The greatest hurdle was the lack of recognition for the value of our work. It was difficult to sell carvings, which only sold a peso or maybe half a peso. But, slowly, things changed. Though the old-timers did not realize it, the carvings became more valuable, to the point where even collectors would take advantage of the situation and come to the countryside and exchange plaster statutes for the carved saints. The old timers did not know the value of what they were exchanging and they fell pray to this trick. Today we even have a small collection which we exhibit in our museum.

NEA: Do you have apprentices or are you, in some other way, transmitting your art to the younger generations? What advice would you have for the young people who are getting started in the trade?

Avilés: Orocovis is the town of the Santeros. Any young man who is drawn to this art can come here. We give them some guidance and they are let loose to pursue their own style. Seven of my ten children are carvers, especially Antonio, who is recognized as one of the best in Puerto Rico. As for the advice I would give young people, I would tell them: not everybody can be a lawyer or a doctor, so if you like this craft, go ahead and start. It doesn't matter if you don't have a teacher. To see the work of a master is enough. Then work out your own style because it is not advisable to imitate the style of the master. But you need time to do this work, and that is something young people don't have these days.

NEA: Do you feel satisfied with your life's work?

Avilés: Yes, I could die today and feel I have done enough, with my children and my neighbors. Eight out of ten of my children make their livelihood from this trade. That is a source of joy for me. If I were to die today, I will at least have left something good behind.

NEA: How could the NEA contribute further to your work and your community?

Avilés: By giving this more relevance. Continue to give these awards. We have very good carvers and different kinds of handmade crafts that would be good to recognize. And to advertise our little museum of saints and old things throughout the island, and outside as well.

NEA: One last question. What are you most looking forward to during the awards ceremony you are going to attend net September 21st, in Washington?

Avilés: We "speak with our hands," you know. We are not good with speeches. We simply want to say thanks for this award and to be there, be present. I have received many awards here in Puerto Rico and was missing some from the mainland. I am very grateful that we are being recognized. My god and the Saints repay your kindness.