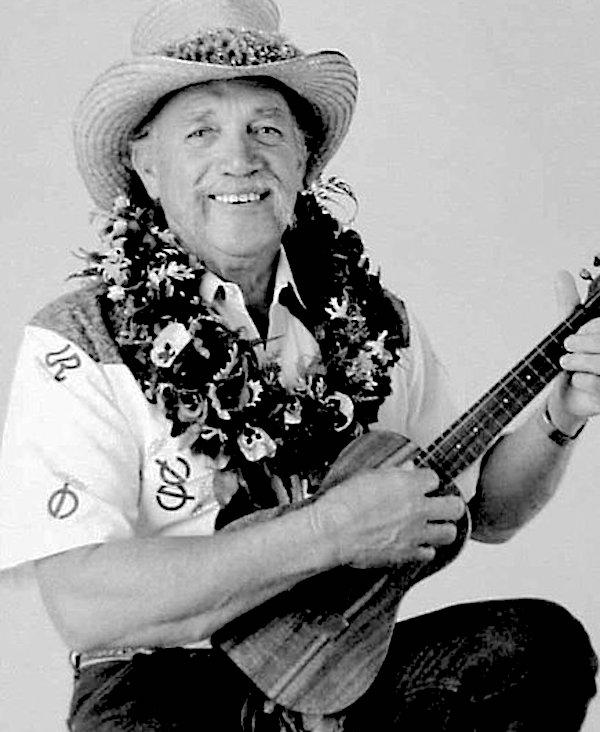

Clyde "Kindy" Sproat

Photo courtesy National Endowment for the Arts

Bio

Clyde "Kindy" Sproat was born November 21, 1930, in the district of North Kohala on the Big Island of Hawaii and raised in the rural isolation of Honokane Iki, a valley two hours away from the end of the road. Transportation to the valley was by mule pack train. His father was part Hawaiian and worked on the Kohala Ditch Trail, maintaining the waterways that fed the great sugar plantations of the early and middle twentieth century.

From an early age, Sproat remembered how his Hawaiian mother played the banjo and sang to the children every night after supper. "We sat on mats that were woven from the leaves of the pandanus tree and watched the reflection of the sun rising up the east wall of the valley, then dancing on the trees at the very top of the ridge before slowly fading out of sight. I sang my heart out. At that time I felt like we were singing the sun to sleep, so in the morning as he crept over the west ridge with his long, shadowy legs, he would be warm and friendly and let us have another good day of swimming and fishing in the stream and doing all the things that little boys do in a day."

Later, the family moved to Niulii, still on the Big Island, but closer to schools, churches, restaurants, and saloons, where Sproat liked to stop and listen to the master slack key guitar players of the time — John Akina, John Kama, and Kalei Kalalia. "That sound and rhythm," he said, "has haunted me all my growing years, and even until this day I listen for the old sweet rhythm of the old slack key. Slack key has changed considerably since I was a boy. Like the old-time slack key, the old-time folk songs of Hawaii have faded into the past. I love the old songs, so I hang onto them and sing them just as I heard them sung.... I had a special feeling for the old Hawaiian songs. The tunes haunted me. I sang, whistled, and hummed them constantly."

In school, Sproat's interest in his Hawaiian heritage was reinforced by his principal. "I went to a little grade school called Makapala School. There each morning, school started with an assembly of students and teachers all standing in rows by grades on the veranda. The first half an hour was doing the pledge of allegiance, the Preamble, singing patriotic songs and all the old traditional Hawaiian songs. Edwin Lindsey, the principal of Makapala School, was a master musician, and under his direction, everyone sang old Hawaiian songs and learned the meaning of the songs. 'Uncle Edwin' was a large influence on the stories and songs I sing today. Our May Day programs were so beautifully done. We sang songs that were written and sung by Queen Emma, Queen Liliu, Lelehoku, and many other writers of that era."

Growing up, Sproat also learned to play the four-stringed ukulele and liked the straightforward accompaniment of the slack key guitar for his Hawaiian songs. He admired the songs of the Hawaiian cowboys, paniolo, who worked on the ranches near where he lived. The Big Island of Hawaii to this day contains some of the largest ranches in the United States under single ownership; during Sproat's boyhood there were many Mexican vaqueros, who were brought in during the late nineteenth century to help develop the new ranching economy. Along with their technical skills, the Mexican ranchmen also brought their musical traditions, especially that of singing with stringed instrumental accompaniment. And as they began to make their homes in Hawaii, they taught tunes, instrument construction, and harmonies to the Hawaiian workers.

Over the years, Sproat developed a repertoire of more than 400 songs. He has preserved the music that originated for the most part in the early twentieth century and reflected the changes in Hawaiian musical traditions from ancient chanted forms accompanied by percussion instruments to falsetto singing and Western melodic forms accompanied by the ukulele and slack key guitar. He has performed at luaus, family gatherings, retirement homes, and community events, and in concerts. "Singing to me," he said, "is the feelings that I have locked up inside that have a need to come out pure and simple."