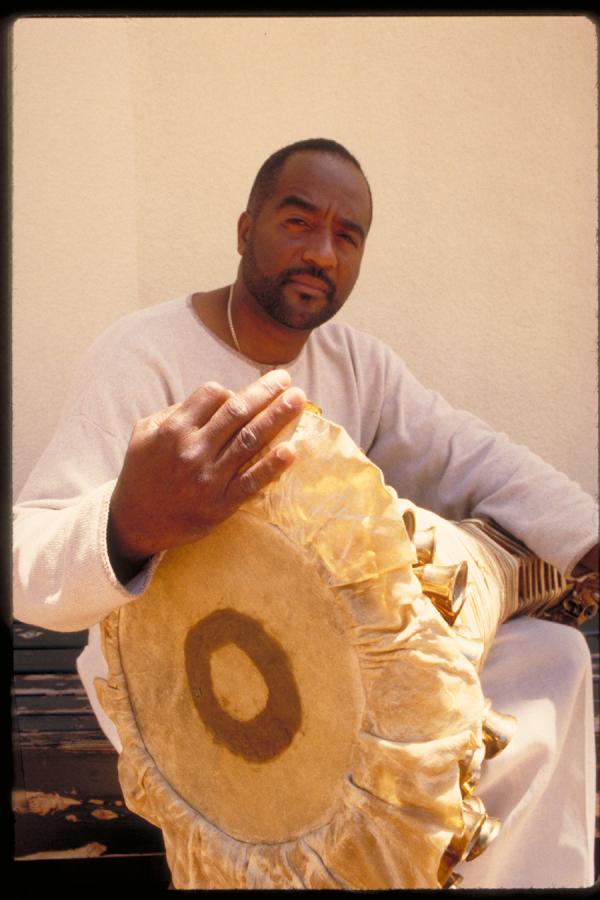

Ezequiel Torres

courtesy of History Miami

Bio

Ezequiel Torres is a master of the making and playing of Afro-Cuban batá drums, a set of three double-headed, hourglass-shaped drums used for Orisha (the traditional religion of the Yoruba people of West Africa) ceremonies. Born in Havana, Cuba, in 1955, Torres became interested in Orisha music at the age of 16 and learned the complex tradition of batá drumming and Orisha chanting from the legendary Griots of Afro-Cuban cultural traditions. He apprenticed himself to batá drummers around Havana, who taught him how to make different kinds of Afro-Cuban traditional percussion instruments including batás, congas, shekeres, and cajones drums, as well as the beautiful beaded tapestries that cover the batá. By the late 1970s, Torres was teaching percussion at Havana's Escuela Nacional de Arte and was the musical director for dance classes at the prestigious Escuela Nacional de Instructores de Arte. Torres arrived in Miami in 1980 as part of the Mariel boatlift and soon established himself as a well-regarded batá drummer and craftsman.

Torres is currently recognized as one of the top batá drummers, drum-builders and beaders in the United States. In addition to making the drums, Torres is also an expert at making bantes (beaded garments worn by the drums at ceremonies) and at constructing shekeres (gourd rattles strung with beads or seeds). His batá drums and shekeres have been on exhibit at HistoryMiami, and one of his bantes (the beaded tapestry that covers the drum) was on exhibit in the National Bead Museum in Washington, DC. From 1995 to 2001, he was the Music Director of IFE-ILE Afro-Cuban Dance & Music, founded and directed by his sister Neri Torres, and continues to teach and perform at the annual IFE-ILE Afro-Cuban Dance Festival in Miami and Colorado.

In 2008, Torres received a Florida Folk Heritage Award from the Florida State Department of Cultural Affairs and has also been the recipient of Individual Artist Fellowships. Torres also has trained young musicians as a master artist in Florida's Folklife Apprenticeship programs.

He regularly performs and demonstrates his drum-making skills at festivals around the country -- including the Smithsonian's Folklife Festival -- and remains a much sought-after music leader and performer at traditional and religious celebrations and events throughout the world in places such as Spain, Mexico, New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Puerto Rico.

Audio samples courtesy of the HistoryMiami South Florida Folklife Center

Photo courtesy of HistoryMiami

Photo courtesy of HistoryMiami

Interview by Carlos Arrien for the NEA

NEA: Tell us, in your own words, what you do.

Ezequiel Torres: Well, I will start by telling you what I do the most. I’m in the percussion business, widely known as afro-cuban percussion. This genre encompasses several different ways of expression, musically speaking. What I do is called the Bata drum. The Bata drum is a group of instruments which arrived to Cuba during the unfair trade of humans, also known as slavery. It was brought by the Yoruba, a widely known ethnic group, from what today is known as Yoruba Land—specifically, from a town called Oyu and Le 'Oyu in what is today called Nigeria. This tradition is rooted, fixed, and well defined. It is well defined as we currently know it from many of the Cuban rhythms that we enjoy today in popular music and even in ways of expression when we play or make percussion music in Cuba. Everything is a part of this integration into this drum family which is part of tradition.

The Bata drums are composed of three drums. It includes a big drum, generally known as the big drum. And in Yoruba tongue its name is Iyá, which means mother. We have an intermediate drum called Omele or Itotele and a small drum, the smallest of all three, called Okunkulo,alsogenerally known as Omelenko.This drum set also constitutes a family known as the talking drums family. There are many small drums [which] are known as talking drums, as they are called in English. And this is one of the groups of drums representing an orchestra, representing a family. And that is part of the tradition that I’ve followed, as it has been followed by many Cuban musicians throughout the music history of my country. I specialize in music and instrument construction, above all else.

NEA: Did you take on this practice willingly or it was something natural, without a specific decision on your part?

Torres: There were many factors, particularly an identity problem. The Bata drums were my life and I was one of the many people that decided to change. At the beginning of my life I was dedicated to [play] music, guitar, specifically and I changed it all to be able to make music with Bata drums, to follow this tradition. I joined many people who now have passed away, many elders, many people who were African descendants and knowledgeable and curators of this tradition. I feel very proud to be able to continue this tradition and keep this tradition to this day.

NEA: Could you tell us a little about the materials, the methods, and the art that is involved with making the instruments and ritual objects?

Torres: Of course. Besides [being] merely an African tradition brought from Africans— an African contribution to our national identity—it is also linked to liturgy, the Yoruba religion, [and] different African ethnicities in my country. But mainly the Bata drums have an incredible popularity due to the musical richness they contribute to the liturgy and to Cuban traditions, to the Cuban music.

It belongs mainly to the liturgy of what’s called Santeria, a Yoruba religion. Others know it as Lucumi religion, but all this is in the context of what I'm talking about – what the Yoruba religion really is. As far as I know, the Bata drums were first constructed in Africa for the worship of Orisha. Orisha is a deity or supernatural being, what could be classified as a saint, an angel. Ni nosotros, por lo general, lo que hacemos es – usamos este termino, em, bien, eh, de los estudiosos de la enología y el folklore, eh, y la sociología como un sincretismo, o sea, eh, como decía, los tambores de bata fueron dedicado en – por la etnia de Yoruba, eh, para el Oricha Shango, la deidad Shango, que representa la virilidad del hombre y el poder del rayo, entonces, estos tambores tienen la habilidad de imitar cualquier sonido de la naturaleza. De eso es de lo que se trata la música del tambor bata. Puede imitar la música del río, del mar del viento, la – varias, [0:09:00] muchas facetas, es muy – en cuanto a representar a la naturaleza. Una música que trata de representar el sonido universal. El sonido de la tierra, exactamente, de eso se trata.The Bata drums were offerings for the Orisha Shango, the deity Shango, who represents the virility of man and the power of lightning, and these drums have the ability to mimic any sound of nature. That's what Bata drums’ music represents. You can imitate the music of the river, the sea of wind; it is very multi-faceted when representing nature. [It is] music that represents the universal sound, the earth sounds, for that matter.

NEA: What about the materials itself and how you treat them?

Torres: It is very important. For example, if we focus on the tradition we see that the Bata drum is made of wood, or branches, and you can gather branches. One of the most important things I alwaystry to teach my pupils is to respect the environment. This is the case in many countries with different musical instruments that are capable of destroying the environment. We need to plant trees, our planet needs trees, and they’re cut for everything. And one of the most widely used things is musical instruments. I’m always focused on trying to use branches of trees, with great results. I can tell you the cedar has great demand, mahogany, and fruit trees. In the beginning, the Bata drums were made of a wood that as far as I know only grows in Africa called Aña, or Ana,and it is a hardwood; it is very very light, consistent, and very sound. In America, it can only be compared to cedar, possibly, or mahogany. And the leather we use is usually goat for durability. We utilize leather from cattle and we always use raw leather as the foundation. It is a system of patches, it vibrates. The Bata drums are vibraphones, that is, they have membrane casings on both sides and are composed of bands – strips of the same leather for pressure. It is a pulling system composed by bands on both sides. It takes a few days, [the] process is a bit tedious, but fruitful in the end with very good results. At the end we can turn what was a piece of wood into a musical instrument.

NEA: What emotions do the drums convey? ¿Que ideas? What ideas? ¿Que es lo mas importante? What is most important?

Torres: The drums are able to convey many emotions, like joy, when it comes to celebration. [They] personify images, personify individuals; it’s very human, very complex. It is a humanized sound. When we interpret, for example, the orishas players, orishas play patterns of joy, sometimes we play as a supplication for the calamities human beings go through. Sometimes we play an epic for the life of those who were the orishas, for example to the Orisha Shango. We always try to show off when we play, to show some of the orisha shango personality or when we play for olgum we try to channel the individual who is able to work, to strive, to build a city, to build peace for humanity. When we play for Obatala, for example, a being closest to the Supreme Being who represents the purity and humanity that all humans should have, we do it with great respect; we interpret music, that is. WEm, tratamos de transmitir ese sentimiento en la música. Esa humildad esa compasión por la vida humana. Es el – ese carácter humano que nos caracteriza a nosotros mismos. [0:16:00]e try to convey that feeling in music, the humility and compassion for human life. It is that human nature that defines us.

NEA: What is most beautiful about your practice?

Torres: I could tell you that what I enjoy most about my practice is bringing the human message through my music. To bring joy every day, every time I get ready to play in public or I am about to make music. To bring you this message, that is a legacy, to put it in words, which I am enjoying today, and to try to pass it to people who are around me, with the same affection, the same love and with the same respect which I interpret and with the same people that gave me the facility to enter this world.

NEA: What it is challenging or difficult about your practice?

Torres: The most challenging is the will to learn. Learning is a serious process; it’s very tedious and you need to make an effort, with complete devotion for everything – “I can do it, I did it, and I would like to give more, to be able to play your music.”But to give your music this context, you need to have a sense of acceptance about overcoming the particular discipline. It is not like saying, “After three days of playing I'll be making music.”

Lo mas preciado que nosotros podemos tener es nuestras tradiciones es basado en el respeto, respeto a nuestros semejantes, respeto sobre todo a nuestros mayores y desgraciadamente esto es una de las pocas cosas que estamos viendo hoy en día en muchos aspectos de la vida. Parece que hay muchos mensajes que nos son muy importantes, como seres humano, que vienen desgranándose poco a poco. Y esto es la – es la muerte de las tradiciones, por lo general. [0:19:00.]The most precious thing we can have is our tradition, based on respect, respect for our fellow man, respect, especially, for our elders and unfortunately this is one of the few things we're seeing today in many aspects of life. It seems there are many messages that aren’t very important to us as human beings and are slowly unraveling. And this is the death of traditions, in general.

NEA: What would you like to change? En esa tradición que tu vives y transmites.

Torres: I hope nothing will change. But as they say, there is a philosophical thought out there that says that everything is subject to change and transformation. But if I could choose, first I would choose respect among people. Second I would ask for respect and honor for our elders. And third, to learn everything we can learn, and learn it with respect and admiration for the people who teach, to make a more humane contribution and to improve the tradition, more than ever.

NEA: There seems to be two worlds of music for you, and perhaps many more. One is sacred, ritualistic and the other is secular.

Torres: Well, I'm very versatile. It includes a bit of my personality, too. All this time I've been doing music, I've been sharing not only liturgical music, but popular music. I’ve worked with many jazz musicians, and made music with many musicians. I have taught many people who have come with respect and understanding that my music is my world. This world is sometimes part of the liturgy and sometimes musical work we have done with many, many people. What I need is my music, my attitude, my behavior and that is what I [am]. Like I said before, I feel proud. If I had to do it again, I think I'd do the same. And learn from and honor with the same respect the people who taught me. I would convey this same love and respect for complacency, to continue supporting this musical tradition, which is quite difficult for many people. A veces requiere de muchos requisitos de conducta. No es solo decir voy a tocar, si no también necesitas requisitos de conducta para poder mantener esta, esta, esta tradición. Las personas, como yo, que se dedican a la tradición litúrgica se les llama Olubata , se le llama. O los tamborero – o usualmente se les dice en el [inaudible] en nuestro idioma se le dice – somos tamboreros, pero nos llama – eh, somos olubata.Y olubata representa ley y justicia, dentro de la litúrgica de nosotros.Sometimes it requires a lot of ethical behavior. It is not enough to just say, “I'll play,” but you also need ethical requirements to maintain this tradition. People like me who are dedicated to the liturgical tradition are called Olubata. We are drummers, but we’re olubata. And olubata represent law and justice, within our liturgy. Y somos – tenemos que ser ejemplo de disciplina que muchas veces, [0:24:00] eso es parte de los seres humanos, pero tenemos el ejemplo de disciplina, sobre todas las cosas.And we have to be an example of discipline, which many times, is part of human nature. We have the example of discipline above everything.

NEA: ¿En que momento de tu – de tu carrera o de tu vida te encuentras? How do you feel about receiving the National Heritage Fellowship award?

Torres: Well, at this time, I am happy. I am very grateful, very proud of all the people who have made this possible. This award that I've received, the National Heritage Fellowship, not only represents me but all the people like me that practice music that is almost never recognized, that is many times exploited, commercialized, and used without regard for tradition or respect for where it comes from. This award means a lot to me.

For me it represents a beacon of hope for a new generation that is out there, like me, dedicated to their music, and with the same discipline that I had. It’s a joy for many, many of my friends, who also struggle playing and doing things, not only in the United States, [but] in different countries around the world. In Asia, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, in Europe, Canada, and South America – our message is global now. And I think that is, for me, a way of expressing joy for all those people like me, those who are out there doing things for our tradition, truly.