George Blake

Photograph by Lee Brumbaugh

Bio

George Blake was born in 1944 on the Hoopa Indian Reservation in the Hoopa Valley of Humboldt County in northern California. He is of Hupa-Yurok descent, like many members of the small Indian tribes that inhabited this region of California before European contact.

As a young man, Blake traveled as a missionary for the Indian Shaker faith. From 1963 to 1966 he served in the United States Army European Operations. After his discharge he enrolled in the College of the Redwoods in Eureka, California, and later transferred to the University of California-Davis, where he majored in fine arts and Native American art. He says, "I wanted to do what the old people did.... I make elk antler purses, and make them as different as I want ... I mean, I could put elks on them, and all these other things and try to show skills an artist would. But I don't. I just like the way they were done a long time ago. And I just keep making them."

Blake has taken skills he developed in college and put them to his tribe's service. He makes the regalia worn and carried in ceremonial religious dances, not only elk antler purses, but White Deerskin Dance headdresses and otter skin Brush Dance quivers.

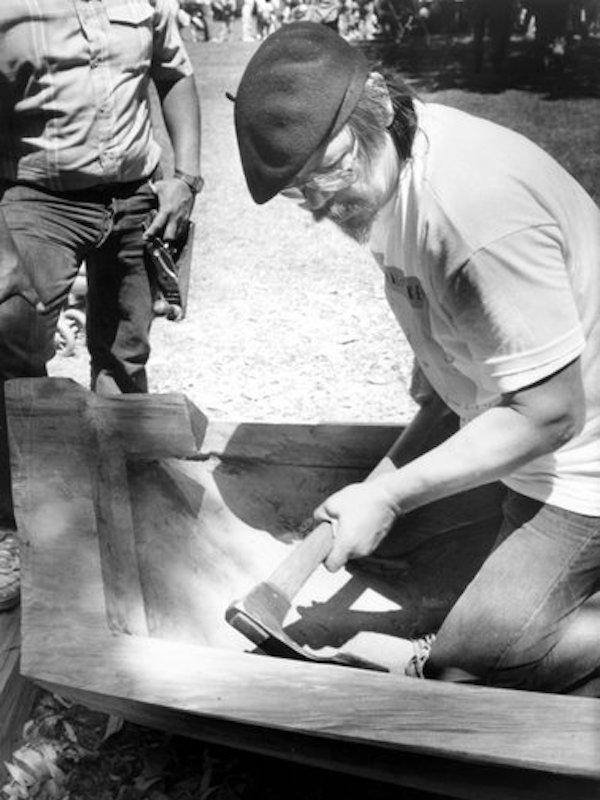

For most of his adult life, Blake has combined library research with oral instruction from tribal elders. He learned to make sinew-back bows from Homer Cooper, who taught him the basics of selecting good wood and the techniques of bow construction. However, even though Blake was able to shape and decorate the bow, utilizing yew wood branches free of knots, he had to experiment with the preparation of sinew and decide which sinew to use. Ultimately, he discovered that he needed the sinew from six deer legs, and over time he identified the intricate methods for removing and processing the sinew for its application to the bow. Then, he studied Hupa and Yurok arrows and refined the process for making them.

From 1980 to 1983 Blake served as curator of the Hupa Tribal Museum, and while there he organized a broad program to teach the traditional arts to younger tribal members. He himself taught featherwork and the making of other regalia, as well as the carving of antlers into Hupa purses and spoons. He also worked to re-create a Hupa dugout canoe; he studied with the last two tribal elders who knew the craft and conducted extensive interviews with them. Though several of Blake's boats are exhibited in museums, they were built for use, and two were launched into San Francisco Bay. Both proved seaworthy.

Blake is able to demonstrate the differences in boat design between "downriver" boats made for use on the Klamath River and those made for use simply for river crossing on the quieter Trinity. Unlike those of Native Americans in the Northwest, Yurok dugout canoes did not have flamboyant carvings and elaborate paintings. Their canoes rise on the water, staying close to the water's surface. Traditionally, an old-growth redwood log was split in half for dugout canoes, using an elk antler wedge and stone maul. The maker then burned each redwood half-log a little at a time, scraping away the burned areas with a stone-handled adze and repeating the process until the general dugout form was completed. Smaller tools were utilized to finish the boat, and before it was launched it was "fire-hardened," a technique that sealed the canoe with the natural resins of the wood. Each boat was believed to have a living spirit, and each part corresponded to an organ of the human body. Nothing was wasted when making the boats. The extracted wood was used to make miniature boats, often carved by young boys just beginning to learn about traditional dugout canoes.