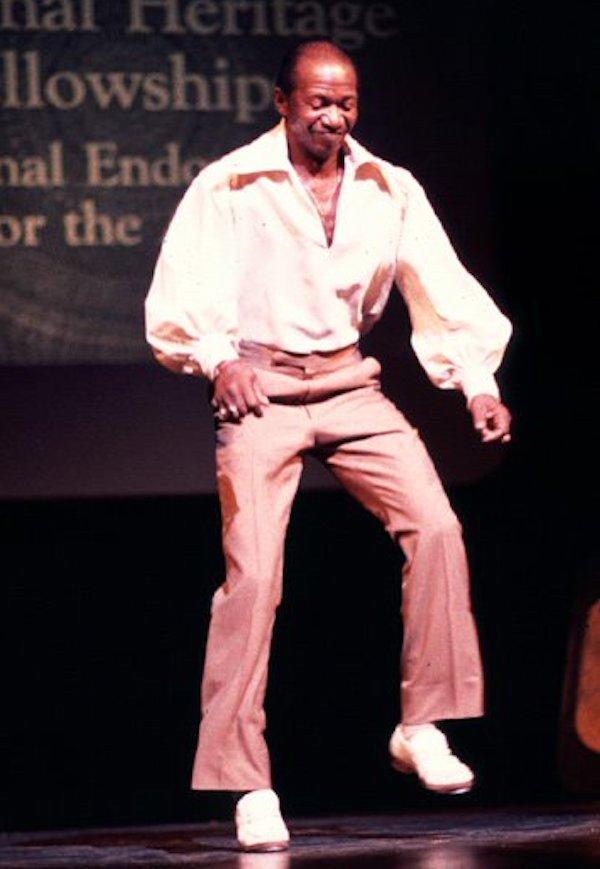

Howard "Sandman" Sims

Photo courtesy National Endowment for the Arts

Bio

Howard "Sandman" Sims may have been born on January 24, 1917, in Los Angeles, California, though he said he was uncertain about the year of his birth. His age, he maintained, was "a matter of opinion." He learned to dance from his father, a barber, as did his 11 brothers and sisters, who all became talented dancers. "Most people first crawl," Sims said, "then start walking. I went right from crawling to dancing. If you can walk, you can dance."

Sims turned professional at an early age and, in the late 1930s, he moved to New York City, after appearing in a film with Count Basie, The Harlem Sandman. In New York, Sims danced on street corners, worked at a variety of odd jobs, and was known as the California Refugee. "I knew people who danced on dinner plates," he said. "There was a man who could dance on newspapers without tearing them. And another who constructed a gigantic xylophone to tap on. I saw people doing the Palmerhouse Shuffle of Kansas City, Missouri."

In 1946, Sims began a career at the renowned Apollo Theatre in Harlem. He danced at the Apollo for 17 years and was acclaimed for his distinctive tap style, which combined the tradition of dance with some of the movement skills he had learned as a boxer. For years, Sims trained as a boxer, but "gave up the ring" after breaking his hand twice. However, it was in the boxing ring that he developed what was to become his specialty, the sand dance. "I used to do some fancy steps," he said, "when I was standing in the rosin box, and the people liked that better than my fighting." Eventually, he put together an act dancing on a board lightly sprinkled with sand, producing a cool, slippery sound, and it was the "sandman" act that kept him going when public enthusiasm for tap dancing waned. Sims felt that the changes in popular music in the 1960s contributed to the decline of tap: He believed that tap was too subtle for the "heavy beat of rock 'n' roll."

Despite diminishing opportunities as a dancer, Sims persisted and formed a group called The Hoofers with 11 other dancers. "It (tap) had died, but we still danced on the streets. People at first thought we was kind of wacky then." Also, around that time, the tap dancer Chuck Green fostered a successful Off-Broadway production called Tap Happening.

By the late 1970s, a revival of interest in tap had spread across the country. Sims appeared in the film No Maps on My Taps, which featured musical direction by vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, with dancers Bunny Briggs and Chuck Green, and old film clips of the tap legends Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and John W. Bubbles. Sims toured to Africa with a troupe sponsored by the Arts America program of the United States Information Agency. Over the course of his career, Sims never forgot his roots. When he had the time, he liked to return to Harlem and participate in "challenge dances" on street corners, just as he did when he was a young man starting out in the business, taking turns to show his skills. "I can dance to anything," Sims said. "I don't even need any music. Sometimes music can even be a hindrance."

For Sims, tap dancing was "most telling a story ... a different story to each person because everybody takes it a different way. It takes a lot of skill because you have to be moving every muscle in your body. The dancing we'd do is what we feel and what we hear. You have to have a vast amount of imagination to be a hoofer. Anybody can be a tap dancer, but being a hoofer is like going over the bridge."