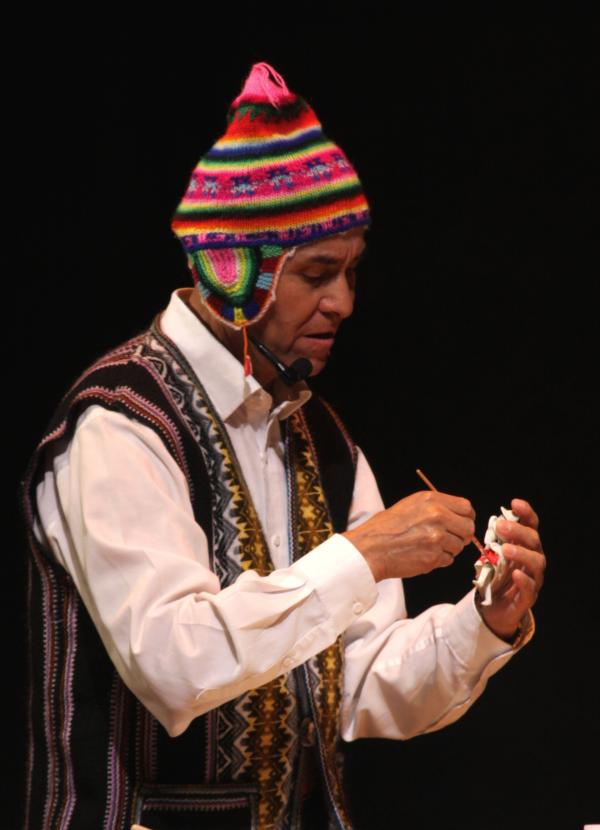

Jeronimo E. Lozano

Photo by Michael G. Stewart

Bio

Jeronimo E. Lozano carries on the ancient Peruvian tradition of hand-crafted retablos, originally portable altar boxes carried by travelers for protection. The retablos, brought to Peru by the Spaniards, often held images of Catholic saints and may have had their origins in the diptyches of medieval European churches. Lozano, a native of the mountainous Ayacucho region of Peru, worked with renowned retablo master Joaquín López Antay. Following in his master's footsteps, Lozano expanded the tradition of retablo making beyond the religious to include the depiction of fiestas, street scenes, and even political commentary. As he became more famous, his work was exhibited in museums in Lima and in other countries of South America. With the rise of terrorism in his home region, his family and friends were subject to displacement and his father died as a result of the tragic circumstances related to the rise of the Shining Path. Lozano, who was studying art at the University of Lima at the time, felt that he could not return home. Even in Lima his life seemed in danger, so in 1994, while on a tour of the United States with a folkloric dance troupe, he arranged for an extended visa. Lozano eventually established residence in the U.S., still considering himself an ambassador for Andean arts. While he maintained the original tradition of hand-painting and hand-sculpting intricate scenes, his subject matter began to reflect his experiences in Mormon Utah and the West. He demonstrates his process and exhibits his work at regional festivals, and in 2002 he received the Utah Governor's Folk Art Award.

Interview by Mary Eckstein for the NEA

[Editor's Note: To help with language difficulties, Kirk Henrichsen, Exhibit Developer at the Museum of Church History and Art, assisted with this interview. Mr. Henrichsen translated Mr. Lozano's responses as the interview was conducted.]

NEA: First I want to congratulate Joeronimo on his award, and I was wondering if he could tell me how he felt when he heard the news?

Kirk Henrichsen: He said he was very happy and very proud and that it is a very big blessing from God.

NEA: Can he tell me a little bit about learning how to make the altar boxes?

Kirk Henrichsen: When he was very young, approximately eight years old, his ability as an artist was known by the people in his home village of Ayacucho, and someone brought him a very old retablo that needed some repair work. He didn't have a teacher at that point, so he learned how to experiment and do it on his own. The people who owned the retablo were also poor mountain people and gave him a young baby lamb instead of paying with money. He realized that retablo-making was a way that he could earn a living and had many ideas, but he didn't know where to get the materials. So he investigated and searched and found out that there were natural rock formations in the mountains of that area that he could make plaster from. He had his mother cook dry corn flour to make a paste which he would mix with the plaster to form figures with.

Then he had o figure out how to paint the figures because they did not have industrial paint available in the mountains. So to make the pigments, he would gather fruit of different colors, most importantly the fruit of the prickly pear cactus or the nopal cactus, which grows a large red purple fruit on it, and from that fruit he could extract a deep purple color. Yellow he could obtain from other flowers, other plants. Cooking herb teas created natural brown colors, which he called café colors. He would then mix the pigments with the juice from the prickly pear cactus, which is sort of natural pasty glue to make the paint to paint the figures with. He said he learned that the imperial Incas used that sort of paint for their decorations of their palaces.

NEA: What sort of subjects were in the retablos he made in Peru? Hoe much of a role did tradition play in his early retablo-making?

Kirk Henrichsen: In the early days of his life the only retablos that were made or seen were the Catholic saint box. The mountain Catholic religion used retablos to teach and indoctrinate the mountain peoples of the Andes, and those were called San Marcos retablos, after St. Mark, and they had depictions of the different Catholic saints. But he didn't feel limited by the old traditions of Catholic San Marcos boxes. He made those and he still does, but he started to add other things like theatrical dramas, historical scenes of the history of Peru or political statements about contemporary politics of Peru. He also started making retablos in other sorts of boxes than the traditional wooden boxes, putting the figures inside of things like hollow gourds or large bamboo suits or other containers.

During his early career, retablo folk artists typically used plaster molds to make their figures, pressing the material into the molds to make multiple copies of the saints to put in the boxes. But Jeronimo never used molds to make figures -- he always hand sculpted or modeled them with his fingers.

NEA: At what point did he begin to receive wider attention for his work?

Kirk Henrichsen: By age 16 he had retablos for sale in the tourist shops of Ayacucho. The Peruvian arts historian, Pablo Masera, came to visit Ayacucho and saw the work and subsequently took Jeronimo his retablos to Lima, and arranged for an exhibit of his work in the Galleria Alliente Francesa, a fairly important art gallery in Lima at that time. That was Jeronimo's introduction to the big capital city of Lima.

But while he was there he received a letter from his father warning him not to return to Ayacucho because the insurgent terrorist groups, the Shining Path, were taking over the Highland Andes areas and trying to destroy the tourism businesses and to limit the amount of Western influence. Artists who catered to the tourist market were being targeted and Jeronimo would not be safe if he returned. So he stayed in Lima for approximately 10 years.

In 1994 he was invited by the Peruvian government to accompany an international folk art group, primarily folk dancers, to come to the United States. With the support of the U.S. embassy and a German group, they paid their way to the United States. They first came to Florida, where they performed and he displayed his art, and then they were invited to an international folk art festival in Bountiful, Utah, which is a northern suburb of Salt Lake City. It was while he was there that he first started trying to understand English because people would ask him questions. They were very friendly to him, but he didn't understand English, and he would answer them in Quechuan. He was invited to remain in Utah and display his retablos in some art galleries in Salt Lake City,

NEA: How did being in the U.S. affect his work?

Kirk Henrichsen: At first it was hard for him to make retablos because he didn't know where to get the plaster or the pigments. He couldn't pick cactus flowers anymore, and so he was introduced to the bright commercial colors and the varnishes that were available in ceramic artists' shops. He liked those bright colors. They were different colors than the natural pigments that he'd used.

As he traveled across the United States with the folk art group that he was with he saw a lot of the history of the United States. He was especially interested in the customs of the native Indians and the cowboys and the religious traditions of the United States. He saw many similarities with the customs of Peru, but also saw the differences. He says the United States has a beautiful history of drama and tragedy and he wanted to depict those stories and customs. Here in Utah, for example, this weekend is the celebration of the coming of the Mormon pioneers, and that is one of the traditional stories he has now come to show in his retablos. The same way that he shows the customs of Peru, he also now makes retablos showing the customs of the place where he lives. He's pointing to me right now to a sketch on his table showing a parallel retablo of Peruvian cowboys and United States cowboys and a Peruvian bullfight and a Western United States rodeo, and Indian dancers in Peru and Indian dancers in the United States. He has always considered himself an ambassador of Peruvian traditions, but he also likes the traditions that the people that he lives with now celebrate.

NEA: What about passing along the tradition? Is he able to do that here?

Kirk Henrichsen: For the past eight years he has been asked to teach retablo-making in schools, and also with disabled groups of people in rest homes or other facilities. This has been arranged through the Utah Arts Council's programs for education. He has really enjoyed being a teacher, making retablos with the young people of Utah.

When he teaches high school or junior high school students, he begins by telling them his history and showing them examples of the retablos about his history in Peru. Then tells them that they should think about their own experiences and tell about their own customs and histories in their retablos. He then lets them do what they want to do. And the results have been very beautiful. The students make small retablos in cardboard boxes about their own life experiences rather than trying to just duplicate his Peruvian customs.

NEA: Jeronimo has had a really long career making retablos. What keeps him so engaged in the tradition?

Kirk Henrichsen: He's motivated by the people who like his art and ask him to make retablos. He says, "I'm not a factory to make thousands or millions of retablos. Each one is an individual work. But that art is for the community and for the people, and that he feels that it is his responsibility to make retablos as long as the people want him to make them."