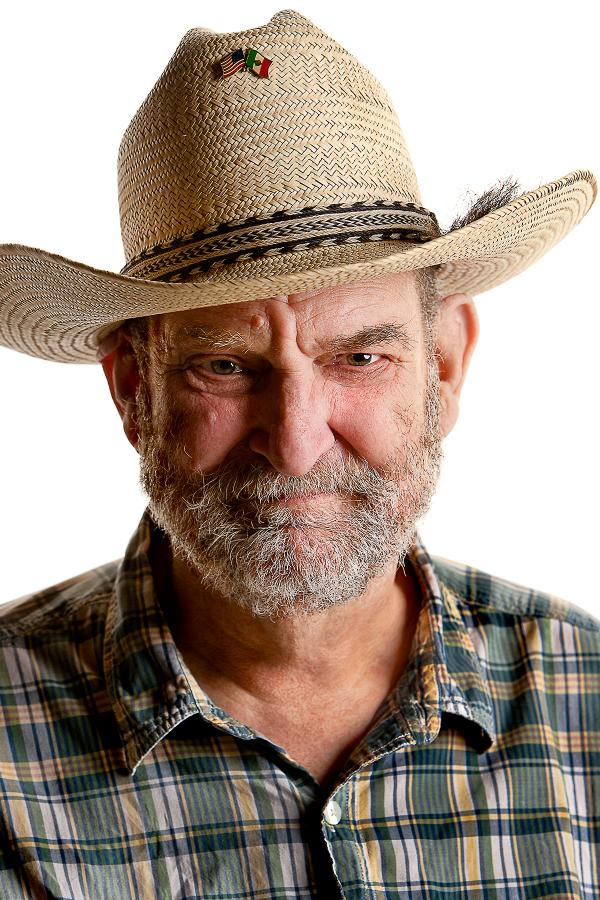

Jim Griffith

Photo by Steven Meckler Photography

Bio

For more than four decades, Jim Griffith has been devoted to celebrating and honoring the folkways and religious expression found along the United States-Mexico border. "Big Jim," as he is affectionately known, is the personification of the intent of the Bess Lomax Hawes Fellowship due to his influential work both as an academic and public folklorist that has proliferated into numerous cultural ventures, including directing the Southwest Folklore Center at the University of Arizona and founding the annual Tucson Meet Yourself Festival.

Born in Santa Barbara, California, Griffith came to Tucson in 1955 to attend the University of Arizona, where he received three degrees, including a PhD in cultural anthropology and art history. From 1979 to 1998, Griffith led the university's Southwest Folklore Center, dedicated to defining, illuminating, and presenting the character of the Greater Southwest. In 1974, Griffith co-founded Tucson Meet Yourself, a festival that celebrates Tucson's ethnic and cultural diversity, with more communities participating every year. The festival currently draws more than 100,000 participants annually.

Griffith has written several books on southern Arizona and northern Mexico folk and religious art traditions, including Hecho a Mano: The Traditional Arts of Tucson's Mexican American Community and Saints of the Southwest. In addition, Griffith has hosted Southern Arizona Traditions, a television spot on KUAT-TV's Arizona Illustrated program. He has curated numerous exhibitions on regional traditional arts including La Cadena Que No Se Corta/The Unbroken Chain: The Traditional Arts of Tucson's Mexican American Community at the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Griffith has been honored for his distinguished service to folklore and the state of Arizona with awards such as the 2005 Henry Glassie Award and the 2009 Pima County Library Lifetime Achievement Award and served as the Grand Marshall for the 2010 Tucson Rodeo Parade. His professional commitment has always been to understand the cultures of the Southwest region and to pass along that knowledge and understanding to the public as respectfully and accurately as possible.

Interview by Josephine Reed for the NEA

July 15, 2011

Edited by Liz Stark and Ann Waller Curtis

NEA: Dr. James "Big Jim" Griffith, many congratulations on receiving a National Heritage Fellowship, the Bess Lomax Hawes Award.

Jim Griffith: Well, thank you very much. I'm still in the state of some shock and denial but it's great. The selection committee must be reading on the wrong line or something like that but it's lovely; it's nice. Bess was a dear friend and it's because of Bess that so many of us were able to be effective and get anything done. Being associated with her through this award makes me very, very happy.

NEA: You are both an academic as well as a public folklorist. Can you give me your definition of what folklore is? What is it that a folklorist does?

Griffith: I've been trying to figure that out for 45 years. Folklorists do different things but it all involves folklore, which is informal patterned traditional communication within groups. I think that definition avoids many of the arguments. Of course, no definition is any good and folklorists are having a difficult time explaining what folklore is, as you are witnessing at the moment.

NEA: Do you think it's fair to say that folklore involves both community and tradition?

Griffith: Yes, very much, but not tradition to the exclusion of innovation and not community to the exclusion of the ability of the individual to innovate and to work within and sometimes expand upon the rules.

NEA: You have written that folk art has a kind of depth in time.

Griffith: A depth in tradition or a rootedness would be maybe a better way to put it. Take lowrider cars for example. Obviously, no automobile has been around for more than a hundred years and lowriders are very definitely a post-World War II phenomenon, but the aesthetic with which lowriders, and especially lowrider displays, are stuck together is very rooted in the Mexican-American world and has strong links to the 18th-century baroque. We're lucky in Tucson to have not only a number of lowrider cars cruising around but also a 18th-century baroque mission church just south of town, and aesthetically those two things are on the same track.

NEA: How did you first get drawn to folklore?

Griffith: I have no idea because I have always been interested in the stuff that interests me now. I can't remember a time in my early youth when I wasn't excited with old customs, old things with tradition, with that kind of stuff.

NEA: Now when you first began studying there really wasn't much of a tradition of folklore or folk art within the academy, was there?

Griffith: A bit, and the silly thing is that I never really studied folklore. There was one folklore class at the University of Arizona in Tucson...and I got my degrees in anthropology and art history. Folklore is just what I was drawn to and folk art was the kind of art I was drawn to. I was almost through with a PhD when I realized that what I was doing was folklore and just as much folklore as cultural anthropology. And furthermore, the annual meetings of the American Folklore Society were a lot more fun than the anthropology meetings.

NEA: Why do you think folklore is important?

Griffith: I think it's important to understand and recognize a dynamic that permeates the normal lives of just about everyone. All God's children have folklore and to not pay attention to these very powerful informal means of communication cuts us off from a lot of understanding.

NEA: I'm assuming you're very interested in storytelling and the stories various cultures tell to themselves about themselves.

Griffith: I've not really specialized in that. I did some things with music and got into storytelling by the back door simply because 60 miles south of the international border, which is 60 miles south of where I live, there is a town which is the focus of not only the region's biggest religious pilgrimage but of a lot of legend cycles about a miraculous statue and of the first missionary in the region, Padre Kino. I never was terribly interested in narrative from an academic standpoint or a presenting standpoint until I came to it through that. However, I come from a family in which there were a lot of stories told. Neither of my parents was particularly terrified of the sound of their own voices and neither of them was terribly interested in letting stark truth get in the way of a good story, and so I've grown up in a world where stories were told.

NEA: The Kino Mission Tours have been going on for quite some time and you were a part of that. Can you explain who Padre Kino was and what those Mission Tours were about?

Griffith: Eusebio Francisco Kino was a Jesuit missionary who was the first European to move as a permanent resident into the now bi-national region that he called the Pimaria Alta, parts of Northwest Sonora, parts of Southwest Arizona. He was a remarkable guy for many, many reasons, but perhaps the most important thing is that after he arrived, nothing was going to stay the same. He brought a new religion. He brought two new languages, Spanish and Latin. He brought crops. He introduced beef cattle and wheat and various other European crops and domestic animals into the villages where he worked, and perhaps most importantly, he started the connection, connecting the Pimaria Alta with the rest of the world. It was a pretty isolated, self-sufficient place, some trading going on outside. Now we can open the papers and read with concern about things going on in Afghanistan and China, exotic places like Washington, DC, and that all is the current culmination of a process that Kino started. On a much more mundane but folkloric level, you'd be hard pressed to go into a Mexican restaurant anywhere in southern Arizona and find more than one or two dishes that didn't include wheat or beef in some way. And of course, beef includes cheese. Now, that's not the case everywhere else, in other Mexican-American culinary regions, but it sure is that way in Southern Arizona. Kino is responsible for that. That's his importance. He founded a lot of missions, which doesn't mean that he built churches. It means that he started these programs of connection and acculturation and directed cultural change in 20-some-odd villages.

The Kino Mission Tours started when a Jesuit historian, Father Charles Polzer, had a chance to do some touring to introduce people in Arizona to Sonoran culture and try, once again, the same thing of introducing strangers to each other. They ran until last year when the Altar Valley just got too grim to try to go to. Still, it takes an armed caravan to get food into Tubutama. There's two cartels fighting each other in the Altar Valley and there was one day when 19 corpses were discovered in this otherwise idyllic rural area in Northern Mexico. So, we don't do the Kino Tours at the moment. I hope they get started again because they were great fun and they got a lot of people familiar with Mexico, with Mexican people, with Mexican culture, and, as familiar as you get in three days, with Mexican food. It gave a lot of people, a lot of Mexican-American people a chance to travel down to where their great-grandfathers or great-grandmothers came from without the anxiety of traveling by yourself in what by now is a foreign country. I hope we can get it going again because they did a lot of good and were a lot of fun and brought some money into some poor communities.

NEA: You grew up in Santa Barbara and you went to school in southern Arizona. Can you talk about what was it was about the culture of Arizona that so clearly drew you? You've remained there for many, many years.

Griffith: There are just so many kinds of people doing so many different kinds of stuff. Southern Arizona has a huge and old Mexican population. I have a friend who's a musician who has the same name as an ancestor who was there in the 1780s. There are families in Tucson that helped found the Presidio, the cavalry outpost, and families who have brought up traditions recently from other parts of Mexico. There are Yaquis. There are Tohono O'odham. There are all the different kinds of people who came for different kinds of reasons: jobs, climate, or Sunbeltishness, and it's just a fascinating place and there's always interesting stuff going on.

NEA: I think part of what has always interested you is the way cultures or folk traditions change as they move across those cultural boundaries. The area in Arizona where you live is really ripe for that because you have all these disparate cultures that also have an amazing interaction with one another.

Griffith: Southern Arizona is an interesting place full of options. You can live in Tucson and never encounter a native Spanish speaker, or you can live in a multilingual neighborhood as I do; you can live in Tucson in a golf destination, or you can live in Tucson among people where golf just doesn't exist. It's really what you care to participate in.

NEA: Part of your life's work has been making people aware of the richness of all the folk art that they live in the midst of and you've done that in a number of ways. One of them is this extraordinary festival that you're the cofounder of, called Tucson Meet Yourself. Can you tell us how that festival began, what you were thinking of, what you were envisioning?

Griffith: Because it began some 37 or 38 years ago, it's awfully easy to color my motivations with hindsight. It started off with me and my wife, Loma, realizing that there was a tremendous amount of beauty being created in Tucson within small communities and there was no real way in which that beauty could be made available to the larger population of Tucson. You could always go to a Tohono O'odham or, in those days, Papago Indian dance where polkas and two steps were played but you'd be outnumbered of course and you probably would never even learn that such a thing exists. You could go to a Yaqui ceremony but it takes a little courage to go on to alien turf and watch things like that.

We realized that there were a whole lot of neat activities going on in Tucson. For instance, I discovered that Yaquis enjoyed old-time fiddling but they had no place to go where they could hear that or bluegrass music without going in to a bar and going into bars cross culturally was a little risky for everybody.

And so we figured we'd produce an occasion where folks could enjoy other cultures and have the different cultural offerings in the town presented with a certain amount of knowledge and accuracy and dignity. This was in 1974. People were still a little shy of the Woodstock experience so we decided that we wouldn't call it a festival; we'd give it a somewhat ambiguous name, which we did, Tucson Meet Yourself. We started going and somehow it caught on. Now at about the same time people would ask me what I thought of cultural pluralism and my gut response to that has always been that we seem to have two choices -- either to kill each other off or love each other.... I was in my favorite Mexican restaurant in Tucson one morning a few years ago and a guy had just gotten off his shift at the mine and had a few more beers that he needed. I was eating breakfast and he was having his end-of-the-day beers and recognized me and held forth to me for quite a while on some of the things that were worrying him, and finally he said, "I don't want to be tolerated. I want to be loved." And I think we all feel that way.

NEA: How did you get buy-in from people? How did you get Yaqui artists to agree? How did you get fiddle players to come? How did you get the creators and the performers to come and present?

Griffith: I live in a Mexican part of town right next to a small Tohono O'odham reservation and have been attending Yaqui Easter ceremonies since the late 1950s. And I am a banjo player and ran a non-evangelical religious coffee house for quite a few years. So in the first year I mostly just invited my friends to participate. I did a little research, a little poking around, paid everybody. It wasn't much because we didn't have much but we absolutely did not invite anyone to perform without paying them. For some of the dance groups and some of the groups who were involved in ethnic organizations, like the Czechoslovakian American Club or the Greek Orthodox Church, the bait was that they ran a food booth and sold their traditional foods. One of the things that people call Tucson Meet Yourself has always been "Tucson Eat Yourself." A lot of people go there for the food and some people go there year after year without realizing that there's anything besides food there.

About the fourth year [of the festival], I was standing next to the stage and there was a group of Ukrainians dancing up on stage and a very obvious group of Filipinos in costume waiting to go on, and the stage at that time was right next to a food booth that was selling Norwegian food. There was a guy advertising it wearing a horned helmet and an imitation bearskin wrapped around his middle, which takes courage in Tucson even in early October. And an elderly lady came up to me and said, "Are you the person who is responsible for this thing?" and I said, "Yes, Ma'am, I guess I am." She said, "Do you want to know what's wrong with it?" and I said, "Yes, I really do." And she said, "It's just like everything else in Tucson. It's nothing but Mexicans and Indians," which shows how what you find is determined by what you think you're going to find but it's also a nice story.

NEA: Folklore and folk art can be a mechanism for community building and the festival is an indication of that. Would you agree?

Griffith: Oh, yes. That was really one of our hidden motives -- community building. It has taken a long, long time but I'm very happy with where it is and what it's doing. The festival is the biggest and splashiest part of my work but it's not the only thing I've been involved in in Tucson.

NEA: No, indeed not. Can you talk about your television show, Southern Arizona Traditions?

Griffith: I have no real explanation of how that happened except I got to know some people over at the university's public television station and said, "How'd you like to let me do a short spot every week about our regional culture?" They said, "Yes," and it was a wonderful arrangement. I didn't pay them and they didn't pay me and we just did it. It was three- to five-minute spots completely ad libbed, no script. We just got a camera and a director free for a morning and went out and shot three or four on location, never with interviews. Once again it was shoestring. I discovered I had the most wonderful job in the world at the University of Arizona, which gave me absolute full right to do whatever I wanted as long as it didn't give anyone a bad name and didn't produce angry letters to the university or to the editors and as long as it didn't cost anyone any money. I discovered very early in the game that steerage arrives at the dock at exactly the same time as first class. The journey isn't as comfortable but it all gets there -- all parts of the boat or the plane or the train get there at the same time, and so we got to be very good at shoestring organization. I'll do the work if you'll kick in a little bit of money and you can have most of the credit -- that was how I got a lot done.

NEA: I watched some of the clips from Southern Arizona Traditions and you did a wide range of things, from looking at mission art to talking about maize to looking at the pictures on the noses of aircraft. Do you remember that one?

Griffith: Well, it's certainly a form of folk art in that it's created by and for a very specific community of combat bomber pilots, because your plane didn't get nose art unless it was being flown. At the Pima Air Museum in Tucson I saw a couple of old bombers with nose art and so I asked around at the air force base and they had a whole bunch of those big, big bombers that were last used in the Gulf War. They had nose art and they were sitting in the airplane storage area. Davis Mountain has such a good climate that they store their planes outside. And so, I got permission and got a crew from KUAT and took my own pickup and went out there and spent a morning shooting. Unfortunately, I was doing so much stuff at that time that I didn't really have a chance to chase after any of it in much depth, sort of like an academic butterfly flitting from blossom to blossom. That was fun stuff. The only regrettable part of it was that people who saw it got the impression that I knew a lot more about nose art than I actually do and had all sorts of wonderful questions for me that I couldn't possibly answer. But, it was great fun and it was interesting.

NEA: Now, you are quite musical. You play the banjo. In fact, you are an award-winning banjo player. When did you pick up the banjo?

Griffith: Around 1961-62. You know, I do love to play banjo.

NEA: And you perform, or you used to.

Griffith: Not as much now. I think maybe this is the time to say that at one point I got another award from the Humanities Department at the University of Arizona, the School of Humanities, for public service in the humanities and I explained at the time that I was given this award that this sort of thing really depends on two factors. One is picking a field or ... picking a region, which nobody else knows about, goes to, or is very interested in. The other thing is to have many of the character traits and several of the skills of an old fashion snake oil salesman and breaking into song is just one of them. I used to know and occasionally record and play with a wonderful old gentleman, an elderly fiddler from the southeastern United States named Leslie Keith. Les Keith, among other things, took the credit for having composed the popular tune "Black Mountain Blues" and was the first fiddler that played with the great Stanley Brothers in the history of bluegrass music. He once said to me, "Jim," he said, "the world's full of people who can play it, but you've got to sell it too." That's what I keep in mind as much as I can. I've got to make it interesting if I'm going to be a public educator, which is what I consider myself.

NEA: Jim, we both know that it's very easy if you're an academic to stay within the academy and really not become a public educator, but you made a different choice. Why did you make that choice?

Griffith: Given who I am, what my abilities are, what my shortcomings are, it was the infinitely more satisfying and easier road to go. Let me go back. When I was training to be an archeologist, which I was first, I noticed that at that time in the mid-'50s the professional archeologists really scorned the amateur archeologists -- with some good reason because the amateur archeologists were basically, by digging in a treasure-hunting way, destroying the knowledge that the archeologists were trying to get. I also felt very strongly that it was the public, whoever they are, that paid the bills and supported the archeologists. It's the public that pays the bills and supports the scholars. I'm not preaching to anybody else, but I got very strong feeling that if I was there at the University of Arizona with all four feet in the public trough, being a state university, I'd better make that public happy and do some nice stuff for them. And so, that's where it, I guess, starts.

NEA: Well, you've done a lot of nice stuff, including curating 11 exhibitions.

Griffith: Tiny exhibitions, one big one and ten small ones in two-room galleries. Once again, it's the steerage principle. I have a lovely time and also I discovered a wonderful fact, that people would pay me to give lectures on Arizona folklore and I figured that if the state of Arizona is paying me to educate people about Arizona folklore, if I accept money for giving lectures on Arizona folklore, I am coming close to violating the law against double jeopardy in the state of Arizona -- being paid twice for the same work or being hanged twice for murdering somebody. I figured I could take those stipends and put them into a bit of a war chest. So, if I needed $400 to, say, start an all old-time fiddle contest, I could take it out of that discretionary fund and that also meant that I didn't have to sell anyone except the participants on what I was doing. So, that's the way I did a lot of what I did.

NEA: You directed the Southwest Folklore Center at the University of Arizona for over 20 years.

Griffith: Almost 20 years. Once again, that sounds probably a little more important than reality. The Southwest Folklore Center in its earliest days was two people and in its final years was one person. But yeah, I was the person who did what was to be done.

NEA: What was the mission of the center?

Griffith: To document and preserve the traditional arts of the folk and ethnic communities of Arizona, to create programs reinforcing that lore within the communities themselves, and to educate the general public of Arizona as to the richness of the folklore of the people of the state. The programs could include, but were not necessarily limited to films, videos, radio shows, lectures, concerts, festivals, exhibitions and anything else that could be turned to that purpose.

The first day that I got that job at the Southwest Folklore Center, somebody called my wife Loma and said, "Where's Jim?" and without even thinking she said, "Oh, he's in hog heaven."

NEA: How did you find out that you received the National Heritage Fellowship?

Griffith: Well, I got a message that Barry Bergey [NEA Director, Folk and Traditional Arts] had called and he left me a message to call him back and we played telephone tag, I think, for a little while and then we reached each other and he told me what had happened and my first response was some disbelief. I tried to argue him out of it I think because that's pretty powerful company to be placed in. He said, "Oh, no, you've got a lot of recommendations and they say nice things about you." He might have asked how I felt to get it and I gave him an answer that I've been giving for the last couple of years [when I've been honored]. I simply told him that I felt posthumous.

NEA: Now, you said you knew Bess Lomax Hawes. Had you worked with her?

Griffith: I could be described, I guess, as having been one of Bess's kids. I never worked with her in the field, but she enabled my job. She encouraged my work. Even when I had no job being a folk arts coordinator or public folklorist, she'd always invite me to back to public folklorist conferences, mostly at the Library of Congress. I loved her very much and took encouragement from her. She was just a tremendously supportive person. She created an atmosphere of non-competitive collegiality among the public folklorists that really has pervaded to this day. Even though I never took classes from her, I can describe myself as one of Bess' kids, proudly and gratefully.