Transcript of conversation with Liz Carroll

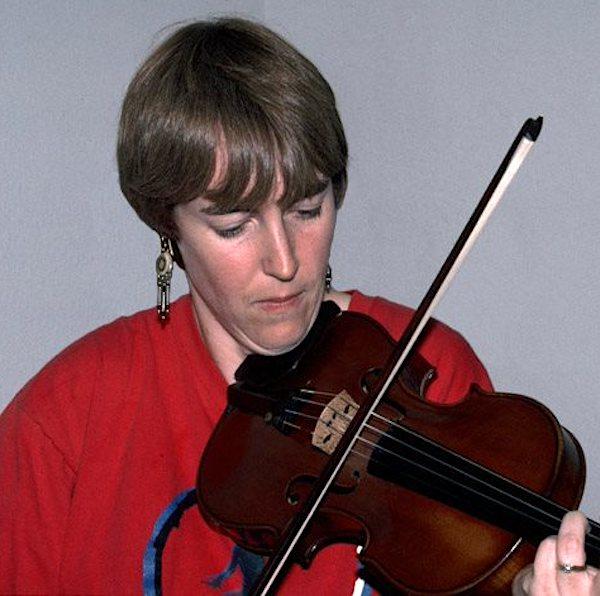

That's Irish fiddler and National Heritage Fellow Liz Carroll playing The Didda Fly and Dodger, it's from her cd, Lost in the Loop.

Welcome to Art Works, the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host Josephine Reed.

Liz Carroll has been recognized as one of the great Irish fiddle players since she won the All-Ireland Senior Championship at the age of 18. And she's only gotten better.

Her first solo recording Liz Carroll, was chosen as a select record of American Folk music by the Library of Congress in 1988, and her 2000 solo recording, Lost in the Loop was named best in the Celtic/British Isles Category by The Association for Independent Music. Liz composes much of what she plays and the breadth of her musical ability is astounding. Her repertory includes reels, set dances, and three kinds of jigs. In 2010, she published a book of her tunes called, Collected, and it's now in its second printing.

Born and raised in Chicago, Liz regularly plays with other Irish musicians in and around her hometown. In fact, in 1999, Mayor Richard Daley proclaimed September 18, ;Liz Carroll Day in Chicago. But her musical reach has always been global.

And now that her children are older, she's added more extensive world tours to her calendar and became a founding member of the international musical group, The String Sisters In the mid 2000s, Liz teamed up with guitarist John Doyle. Not only was their CD, Double Play, nominated for a Grammy Award, but Liz and john played at the White House for President Barack Obama on St. Patrick's Day 2009. 2010 was a banner year for Liz Carroll. The Irish Voice named her one of the year's most 50 influential women. And she was honored at IBAM: Irish Books, Arts, Music with a Cultural Arts Award for Outstanding Achievement.

We at the National Endowment for the Arts like to point out that we were ahead of the curve when it came to appreciating the cultural contribution that Liz Carroll has made since we named her a National Heritage Fellow back in 1994. I recently spoke with Liz Carroll recently and began by asking her what makes Irish music, Irish music.

Liz Carroll: Well, that's a good question. <laughs> It's a very simple music, I'll say that. I know that when I teach, if I'm describing to them how to pick up by ear, let's say for example, if you have a core note, amazingly, everything is almost one note away or two notes away, and that's pretty rare in music. There's no gigantic hops. A lot of times--so if I say you're picking up something by ear, I'll tell them, "If you go one note away, up or down, and if you're wrong that time around, then just go the other direction the next time." But it is amazing how small the distances are between the notes. Now, with Scottish music, there's much bigger leaps, and you can really tell that that's just a different music. I also kind of say this, not to be going on, <laughs> but it can be very fast music, and a lot of times that's why a lot of people are out at the bar, and they're just kind of stomping their feet and throwing their beer about. <laughs> And when they're doing that-- but even with that very fast and happy music, if you slow it down, not only is it those small, little intervals between notes, but I would say that it also has the effect, when you slow the pieces down, of the very sad tunes, which are built to be slow. Does that make sense, Jo?

Jo Reed: I think it does. You know what? Why don't you give us an example?

Liz Carroll: Well, let's see what I can do here. Well, if I play a little bit of a, like a kind of a classic Irish eire, there's an eire that's called The Coolin', and it goes like this.

<Liz plays fiddle slowly>

Liz Carroll: So almost everything that was going on there, you can hear that the little jumps are like little thirds, the way people into music will know thirds. But if you think about it in terms of "do re mi," "do mi so" <laughs> would be like a little triad, so those are like little jumps of two notes apart. And, now, that's kind of what's going on there. If I play you a happy tune now, <laughs> let's see if I'm going to find a good one. Let's see.

<Liz plays faster tune in minor key>

Liz Carroll: So all these notes are very close together again. <laughs> but I'm playing faster, and you could stomp your feet to that. But if I slow that piece down...

<Liz plays same piece slower>

Jo Reed: Ah, yes. I can hear that.

Liz Carroll: Yeah. It's a funny thing. And for us that really know the tunes, I think a lot of people hear Irish music, and they might not be able to tell one tune from another. And in the worst cases, they think they're all the same tune. But in... <laughs> but for us that play it, like us, at some point we get fast enough that we can really pick them up at full speed. But as you're learning them, you really learn that there is a big difference there, that each melody is its own little game and its own little story, and we get to hear, even as we're going fast, we can hear this little character of it being happy, but yeah, being very sentimental at the same time.

Jo Reed: What attracts you to Irish music?

Liz Carroll: Well, it's beautiful. <laughs> I think it's in my blood. My father was an accordion player. My mom's father was a fiddle player. We heard not a lot of music outside of Irish music, but I really was attracted to it, and I always really liked it. I just have my brother Tom and myself. We just have the two of us in our family, and he avoided that Irish music like the plague. <laughs> It was not particularly his thing at all, so he was the guy that would be buying all the rock records and following that. He's come around since. But I wasn't particularly attracted to the---any to the rock or any of the things that were going on. I really liked <laughs> hanging out with these mostly older people, playing their flutes and tin whistles and pipes and fiddles. Who knows how you come to like that? I just feel like it was just born in me to enjoy it and to like it. You can like the Irish music on many different levels. You can really like the ballads of people like the Clancy Brothers. You can shun the Clancy Brothers and really only want to hear old-style sean-nos, which is the Irish word for "old-time" or "old-sound" singers that are unaccompanied, kind of with their eyes closed, sitting in a corner. You can have people that really want to have The Irish Washerwoman, you know, belt it out <laughs> on a fiddle, kind of like single bows for the whole thing, and there'll be a whole other gang of people who love Irish music, that would say they love Irish music, and yet that wouldn't be the Irish music that they love. It's a small world, but this is a big world, this Irish music."

Jo Reed: When did you start playing music in general, not just the fiddle?

Liz Carroll: Well, I started playing at my house. I think that my first instrument was the accordion. My parents got me a little toy, a little Coleco piano accordion. And I think for a lot of kids that like music, they do tend to be attracted to that part of the toy store. <laughs> So I was attracted to that part of the toy store. If there was a toy trumpet, anything to hit or play on, I liked it, so I used to get them little musical play instruments for presents, and I loved them. So I had this accordion. That same brother that I was talking about stepped on that same accordion, <laughs> and in the process of really crying over that, my father put his accordion in my lap, and so I started picking out tunes on there. The first formal lesson that I had at all was on the fiddle. There were no accordion teachers, and my dad didn't really teach anything. He just put it in my lap, you know? And it's kind of like, "Do what you can." And kind of he did that, too. He wasn't really somebody that could name a note or slow down a phrase. It's basically he would pick up the accordion, and he could start from here and go yea. <laughs> And somehow he got there, and it was quite funny as I was growing up, because I think it made me maybe particularly tolerant with just about anybody, for any reason, not just music, because it was just amazing that he played this lovely music, but if I slowed him down and said, "What is that one note?" Oh, it was just unbelievable that he couldn't pick it out. So that just told me that people are built differently, and to be a little bit tolerant of that, and that just because they don't maybe do it this way or that way doesn't mean that they're not making nice music. And so I went for violin when I was nine, Jo, and I have a little story on this. Do you want to hear it? <laughs>

Jo Reed: Oh, definitely.

Liz Carroll: This is kind of good. When we, living on the south side of Chicago on 55th Street, Garfield Boulevard it's called in that section of 55th Street-- and when my parents moved into this apartment building on the second floor, there actually was a piano in that apartment, and they asked did my parents want to keep that piano? And they said, "No, no, no." Because we were little, and they just thought we'd be making a whole racket with that piano. But when it came time for a chance to take lessons, and this was offered, I think, at--how old are you in when you're nine? Maybe fourth grade?

Jo Reed: Yeah.

Liz Carroll: Fourth grade. There was a nun there, a Sister Francine, and she taught piano and violin, and I really wanted the piano, so my parents bought a old upright piano and had it delivered to the house, and they couldn't get it up the front stairs, and they could not get it up the back stairs, and, like I say, the same nun was teaching violin. So my mom just went, "Come on, try the violin. Your grandfather plays. And if you don't like it in three months, you don't have to do it." So I went in, and I loved it, and who knew? So that was a big surprise to me that I just was infatuated with it, and I loved it, and I really just never put it in my case. I just kind of kept it out. Get home from school, grab it. If there was a chore to get out of, grab it. <laughs> I liked that it got me out of lots of vacuuming and dishes.

Jo Reed: Now, when you were given lessons, you were given-- I'm assuming you were given lessons in classical music or...?

Liz Carroll: No, the--

Jo Reed: More traditional Irish music?

Liz Carroll: No, no. I didn't take the classical music very far, and I always kind of regret that now, because I kind of think if I had actually known what it was, I think I would've been more interested. But my parents, they didn't find the classical station on the radio, they didn't buy classical records, and so we really didn't know what that was, or I didn't know what that was, but I knew what the Irish music was, and so I really, really pursued that. At some point there's a flute player in Chicago whose name is Noel Rice, and he's still teaching and all here in Chicago, and he asked me would I teach Irish fiddle. So I, probably maybe 16 or 17, started doing that, and I used to do a good bit of it in Chicago. Now there's a lot of camps that are dedicated just to Irish music, and in those camps you might have maybe three or four fiddle teachers, two or three tin whistle and flute teachers, pipe teachers, piano, singing, like that. So there's loads of them now, and they're all really kind of all around the country. You could be inâ¦.you could probably do that for a living... <laughs> at this point, because there's enough. You could be in Colorado one week, you could be in New York the next week, you could be in Tennessee the next, you could be off in France the next, you could be off in Ireland the next. You'd be a lunatic if you did, but you could.

Jo Reed: There really is a resurgence in traditional Celtic music, isn't there?

Liz Carroll: Yeah. Yeah. It goes in different little stretches. A lot of people would point to that maybe Riverdance and Lord of the Dance brought the profile way up, and I think that's really true. The Chieftains are going to be in town here in Chicago, and I know they're on tour now, and The Chieftains is the name of a really great group out of Ireland, has been going a long time. I think it's their 50th year of existence. They've been very influential. I remember Eileen Ivers, who's a great fiddle player, and she used to play with Riverdance, and she talked one time about "the session" really being the great equalizer.

Jo Reed: What is a session?

Liz Carroll: It's where you just sit down with other musicians, and there's no show, there's no particular audience. You're just with other musicians, and you're sitting down, and you're playing from a repertoire of all kinds of tunes that you found interesting both growing up, and along the way something that attracted you off of whatever-- the latest album of this person. And it's a great spot to just kind of see what's going on. I don't know if most people would know that side of things. It probably doesn't even look that inviting <laughs> if you walk into a pub, let's say, and there is a session that night, and it can be a lot of people playing instruments, but basically they turn to each other in a circle, and if you're not playing, you're not really in that circle, or you're kind of outside of it, so you might be sitting at another table and not in the thick of that meeting. Yet, for people that really love the music, they say this is the bee's knees. This is the best thing, period.

Jo Reed: It would be like a jam session for jazz.

Liz Carroll: Yeah.

Jo Reed: When did you start composing, Liz?

Liz Carroll: I kind of started composing right off the bat. I don't know why. <laughs>

Jo Reed: You mean when you were nine?

Liz Carroll: Yeah. Yeah. Oh, I think probably before it. I was always picking out little melodies. So I don't know what that is. I know that you can definitely start later. You can be an adult and just suddenly find out that you can do this. For me, I always kind of did it. Before I knew how to write anything down, and before we had a tape recorder, I think there's probably--there's loads of lost bits of music along the way. And even when I started to learn how to read music, I still have bits of sheets of paper at home of just whole notes-- this would be just your little bagel-- on sheets of paper. <laughs> I don't know what any of those tunes are, either, and I think at some point, I realized, "Oh, I don't know what it is," because I didn't know how to put the timing in, and I didn't know how to put in the time signature, and I didn't know how to put in the key signature. <laughs> So there's a lot of lost tunes there, too. But they are there, so yeah, probably around eight and nine I was making up tunes, and probably before on the accordion, but those are completely lost because we didn't get a recording device till maybe I was around eleven, ten.

Jo Reed: Chicago seems to me to be really instrumental for you as an artist, as a fiddler, as a composer.

Liz Carroll: It's a great town. It's a great town for the Irish. I grew up on the south side, as I said, and there was a great gang of people that were there that moved from Ireland, including my parents. There was a great gang that moved to the north side of Chicago. On Sundays, we used to meet at the basement of Old Saint Pat's Church downtown, maybe not every Sunday, but maybe once a month--to play tunes and meet. It's a great town for Irish music. It's a great town for every music, though. So, as I was growing up, and, like I say, as that brother would be playing other music in the house, and as we got old enough to get the car and go out, we would go out and hear blues at Kingston Mines and Theresa's and different places, and there's always concerts coming through, and there was folk festivals that were near enough hitting distance, including the Chicago Folk Festival that just went by, and you could go there and you'd meet all kinds of people playing. So, what a great thing? So you got to hear, for me, I got to hear the violin doing a lot of other kinds of music.

Jo Reed: Now, Liz, you're playing this traditional Irish music in Chicago. When was the first time you took that music and sort of reversed it and went and played it in Ireland?

Liz Carroll: I went to Ireland when I was younger because my grandparents were there, so we went over when I was five. We went over when I was 10, which was a great time, because I had just really started the violin. And, like I say, that grandfather played, and he was there, and we got to play together. After that, I was in an Irish dancing school in Chicago called the Dennehy School, and we went and did a tour in Ireland in-- I'm going to show my age now, but 1971, which was a very, very jolly, jolly experience. We had a lovely accordion player along on that whose named was Paddy Cloonan, who's still playing, and Mary McDonough was on the piano, and a young Michael Flatley was playing the flute and the whistle and dancing, and I was along on the fiddle. Just great fun. You just felt like, "Wow, finally we're in the thick of-- this is where it's at. This is"-- everywhere that tour went, musicians came out, and there were parties, and there was hanging and sessions, like I talked about, and relatives. <laughs> And so I really loved it. Eventually, I got to go back for the flackhills that were in Ireland. There's a competition over there that's called the All Ireland, and I went a few times to that, and I got a second my first time over there in the under-18, and I got first the next year in the under-18, and I got first in the senior the next year. And this kind of put you in maybe people started to know who you were, because the next nice thing that happened was that it was the bicentennial in Washington, D.C., in 1976, and I really don't know if people like myself and Jimmy Keane and Michael Flatley would've been known if we hadn't been going over to those competitions in Ireland, because when they were putting together people to play at it, they did come to Chicago, and all of us got to go, as young people. And again, here we are in the thick of it, and we're more and more realizing that we love it. And I got to go off on a tour with the Green Fields of America, something put together by this fellow Mick Moloney, and toured there, and yeah, who knew? I really, all the time, was going along, going to school, figuring maybe I'd be a schoolteacher, and then the wind blew another direction, and all these nice things have gotten to happen. I love going to Ireland. It's still the place to be inspired. You go there, and it's in everybody's blood, really, and you sit in there among them, playing, and it's a workout. <laughs> It keeps you honest. You learn a lot. It's a really high level, and I think that all of us American-born would really give kudos to Ireland to be the place that we just absolutely love to go, and it refreshes us, and it tells us why we're doing it.

Jo Reed: When you play, or when you compose traditional Irish music, is there strains of Chicago in it? Because it's very fresh, and you put your own stamp of individuality on it, and yet, at the same time, it remains traditional. That seems to me to be kind of a juggling act.

Liz Carroll: Yeah. I used to have people kind of say, "Well, you're an American fiddle player, and I think you were trying so hard to fit in with this tradition that you"-- I used to not like to hear that. But at the same time, I didn't really change what I was starting to do. I really liked chords. I think maybe that's the accordion player in me. So double stops on the fiddle really weren't kind of sort of being done in any of the old recordings of Irish music, or even when I started growing up, but I kept kind of wanting-- especially if it was a tune of mine, you'd want to kind of tell people what you were hearing, chordwise, if they didn't know the tune. And so in describing that, I think I did used to put in a lot of double stops, and I still do it. I still love doing it, and I still love just kind of pointing out what I'm hearing. And so if that makes me a little bit more American-sounding, then there, so be it. It's a funny thing that a lot of the musicians over there in Ireland now, I think, are really, really checking out American old-time and bluegrass music. I think if there's a particular thing, if I can say, in my playing, is at some point-- well, there's a kind of music that's called-- well, it's Kerry music. It's from County Kerry, and they play a lot of polkas there, and one move that they kind of do with their playing is this. Let's say if I was going to these four notes... <plays four notes on violin> okay? So that's a melody. If it was a polka, it might be going... <plays same four notes twice>, but they might put a little bit more of an emphasis into the second note by kind of dipping your bow onto the strings. In other words, you're pressing harder, and you're moving, so that you start to get a sound that goes like this. <plays again, putting emphasis on the second note> Does that make sense?

Jo Reed: Yes.

Liz Carroll: Because it's Kerry music, funny enough, these polkas, a lot of the bowing will go from the beat to the off-beat, like if you're going to do two notes on a bow. And, funny enough, American music also kind of goes from the beat to the off-beat, so that you're kind of going, you're tying these two notes together. <plays two groups of two notes> But in regular reel playing, you wouldn't really tie those first two and the third and fourth note together. Instead, you would've tied the second and the third note together, and then that sounds like this. <plays four notes with second and third notes slurred together> So that's a different animal, and funny enough, when I run into classical musicians, and lot of times if it's like these things where an orchestra is going to back up an Irish player--and this happens every once in a while, funnily enough, and sometimes I'll look back at the musicians, and I'll say, "You know, there's a little thing with the bowing." And all the violinists will go, "Yeah! What's, wait a second. What's going on? And I'll just tell them that, that it's really going, "Dump-dah-DUMP-dah-DUMP-dah-DUMP-dah," rather than, "Dah-DUMP-dah-DUMP-dah-DUMP-DAH-dum." And once they switch that over, they go, "Whoa." And if you switch that over, that's really Irish music. And so you don't have to do those stresses, but I've really started really kind of pushing those stresses, so I think that's part of my style, if you want to hear a little bit of that in a tune.

Jo Reed: I would love to, and actually I would love to hear some of that in a tune right now.

Liz Carroll: Fantastic. <laughs> Okay. Well, maybe I'll play it a first part that I don't do it, and then I'll play a first part again, and then I will do it, and then you can see what you think of that.

<Carroll plays violin>

Liz Carroll: And then, Jo, I can mix them up. <closer to mike> And then, Jo, I can mix them up, so then they can play off of each other. So would you like to hear the whole tune?

Jo Reed: Oh, yeah, please.

Liz Carroll: Okay.

<Carroll plays violin>

Jo Reed: Brava! That's beautiful.

Liz Carroll: It's just a great old trad tune.

Jo Reed: How did you hook up with John Doyle?

Liz Carroll: Well, I was doing an album a few years ago, and you were talking about the Chicago connection. It ended up being called Lost in the Loop. And when I was doing that album--

Jo Reed: And I just got that connection!

Liz Carroll: There you go. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Oh, my God. Where've I been? Oh, my God. That's so embarrassing. Oh!

Liz Carroll: Do you know what, though? I didn't think of it first, either. I was trying to think about how that tune worked around, and again, that brother of mine was helping me out, and saying-- "Okay," I said, "I can't come up with a name for this tune." And he says, "Well, what does the tune do?" And I said, "Well, it loops on itself. It keeps looping." And then he said, "What about The Loop?" And I said, "Well, what about Lost in the Loop?" And then we just went, "Oh, my God, look at the Chicago connection. It'll be perfect." <laughs> Plus, I've gotten lost in every section of the Loop. <laughs>

Jo Reed: Okay, so John Doyle.

Liz Carroll: Yeah, yeah. So... well, he was playing with a band at the time that was called Solas, and I had asked Seamus Egan, who is the leader of that band, to produce this album. And I hadn't really done a solo thing in a while, so I really wanted to have somebody else's ears, and I was really enjoying every recording that that band was doing. And their guitar player was John Doyle. And he's a terrific, terrific guitar player, and I think it was just exactly where my style was going right then. I just really kind of liked the dynamic playing that I was hearing from John. I don't think I really realized that he was also going to be the absolutely beautiful slow player that he is, and in fact who knew he was going to be just so well-rounded in every way? Because he's ended up going off and playing with an awful lot of people. But he's just terrific. And after making that album, my kids were just getting old enough that I could say, "Okay, I'll go off for a couple weeks and go on tour." So I went off to England and Scotland, and asked John if he'd like to come along and do that. As often happens--it sure happens in Irish music--as often happens, you could have a lot of people on a recording, but you can't go on the road with all of those people. Especially, a lot of the places really just kind of hold 100 or 200 people. You could never afford all the rooms and the traveling. But John was able to do it, just so as a duo we went off, and it was just such, as the Irish say, "a great craic." It was great fun. <laughs> So here he is. He's fun, and he's a great player, and he wanted to do it. And so I just feel like we've had a great run of doing, that he was on that album, he was on the next one that really just had my name on it, and then we got to do a couple of albums that had both of our names on it, and it's been fun.

Jo Reed: And you did Double Play, which was nominated for a Grammy.

Jo Reed: But you really are bringing Irish music into the 21st century in new and adventurous ways that still somehow honors the tradition.

Liz Carroll: Well, I would like to think that I've definitely tried, sometimes you could go bigger. I kind of find that I constantly go kind of smaller. I really like to look at a tune, whether it's an old tune or a new tune, and I really like to take a look and see what might be there, and so that's kind of maybe going more microscopic than big, but it's me being me. Luckily, I get to still do it. But it could be that I grab bass players and drummers and dancers and a big show, but I've really liked just going along this way, and just keeping it pretty spare. Would that make sense?

Jo Reed: Yeah, and we all like it, too.

Liz Carroll: Well, that's very nice.

Jo Reed: Now, you're working with Cormac McCarthy, who's a pianist.

Liz Carroll: Right. Well, Cormac is here in Chicago, amazingly, and just is a wonderful piano player, comes from Cork. And I was really just taking a look at the city after doing a lot of bopping around with John Doyle, and he was just getting into loads of other projects and wasn't going to be available, and Cormac had just moved to Chicago to go and do jazz at DePaul University, so he's over here, and I was like, "Wow, here's this really good piano player, and it's a different sound and it's a different person, and he's in Chicago. Holy Cow! This is-- this would be great." And there's a lot of musicians that are in Chicago, and they're all really great. It just was a chance to play with a piano, and I think all the piano players in Chicago right now, they have day jobs. <laughs> So here's somebody that's really playing music, although really his day job is jazz, not particularly Irish. But his roots are kind of like mine. He also grew up with traditional music in his home. His father's a flute player and a fiddle player, and he went to sessions, and his sister plays the concertina, and it's-- you know, it's funny. It's kind of like the same background. He was telling me the other day that he really was avoiding the whole Irish music when he was going to high school. I think that's very close to a lot of people in Chicago, too. Certainly, all the boys put away and hid their fiddles, <laughs> or stomped on them so they didn't have to carry them to school. It just was never a good look, was it? <laughs> So he was funny. He was like-- he was kind of the same way over there. They wouldn't be that anxious to be seen playing that trad music with those old guys, but he's come back to it, and he's really loving it.

Jo Reed: I'm going to ask you to play something else. Is that okay?

Liz Carroll: Sure. Let's see. What would you like? <laughs>

<Carroll tunes violin>

Liz Carroll: Well, the last thing I just played was a reel, so what if I were to play a jig for you?

Jo Reed: <gasps> Perfect.

Liz Carroll: And since it's around St. Patrick's Day, the tune that I was talking about before, The Irish Washerwoman, sometimes it gets a bad rap... <laughs> because it can be that fiddle player in a pub at one o'clock in the morning that has to play it really fast, and it's all about that. But it's actually a really quite sweet tune, and it is in old books of Irish music, and maybe I'll just play that little tune for you.

Jo Reed: Sounds great.

Liz Carroll: I also have some little variations. Plus, I might see what happens. Let's see. We'll just play it for you, okay?

Jo Reed: Okay. I'm ready.

<Carroll plays The Irish Washerwoman>

Jo Reed: That was fantastic! Is that as much fun to play as it is to hear?

Liz Carroll: <laughs> Yeah. It's actually a riot. I was just having a great time there.

Jo Reed: Liz Carroll, thank you so much for coming in. I really appreciate it. And thank you for playing.

Liz Carroll: Thank you, Jo. It's been a total pleasure. Happy St. Pat's to you.

Jo Reed: That was Irish Fiddler and National Heritage fellow, Liz Carroll

You've been listening to artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

Excerpts from The Didda Fly and Dodger from the album Lost in the Loop, performed by Liz Carroll used courtesy of Compass Records Group. Excerpts from Before the Storm/The Black Rogue from the album Double Play, performed by Liz Carroll and John Doyle, used courtesy of Compass Records Group.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes Uâjust click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Next week, Sarah Greenough, editor of My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.