Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, this is Art Works. I’m Josephine Reed.

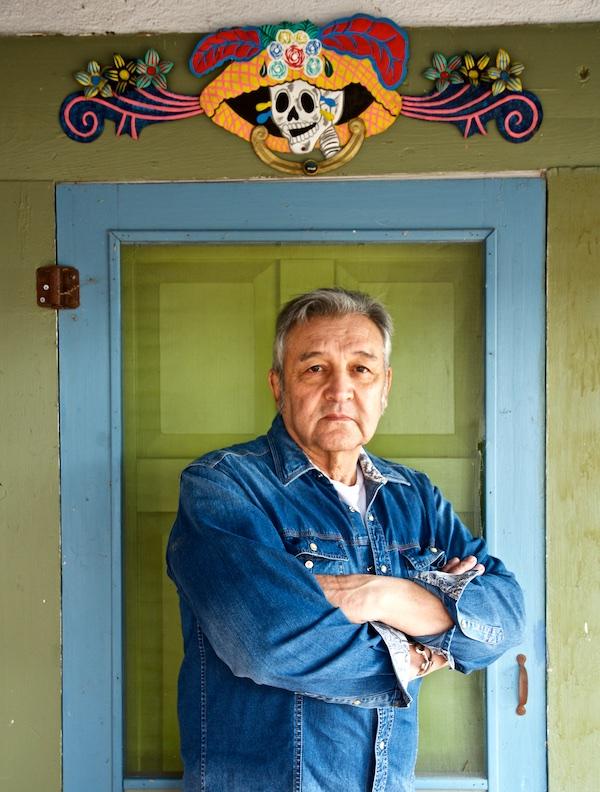

Today, a conversation with sculptor and 2023 National Heritage Fellow Luis Tapia. For five decades, Luis Tapia has helped to revitalize and transform the art of the santero (saint-maker), a centuries-old Hispanic tradition practiced in New Mexico and southern Colorado. With his vibrantly colored wooden sculptures, Luis reimagines the lives of the saints—and he places them among us as immigrants crossing a border, a man in jail, a grandmother protecting her grandchild. It is extraordinary art that simultaneously embraces tradition, cultural pride, and the complexities of modern society.

Luis Tapia effortlessly blends the sacred with the quotidian, the nostalgic with the contemporary, humor with biting social commentary. He has created altarpieces for local churches, and has also reimagined altars as colorful lowrider dashboards. Yes, you heard that right. Now, if you don’t know the art of Luis Tapia, then before you listen to my conversation with him, you might want to go his website Luistapia.com and check out his art. I promise—you’ve never seen anything like it. He tells complicated stories with his carvings and today, he shares his own story with us.

Luis Tapia: I was born in a little village outside of Santa Fe. It's called Agua Fria, and it's more or less a farm community. I lived there most of my childhood life until I was about 18 years old.

Jo Reed: And what about the culture in which you were raised? Describe that.

Luis Tapia: Oh, it was very rural, you know, very Hispanic, lots of cows, lots of apple orchards. A very Catholic, Hispanic Catholic community.

Jo Reed: And did you draw or paint or carve when you were a kid? Did you see people doing that?

Luis Tapia: As a child, yes, I loved drawings a great deal and come to find out in my later life as an adult that I'm dyslexic. So at the time, I didn't realize that I had this issue and nobody did. I was found out in my later life that I was dyslexic and so consequently, I guess as a child, that's what I loved to do was to draw. But when I got into the school systems, they found out that I was paying more attention to my drawing than I was in my regular studies and of course, I couldn't read and stuff like that. So they took drawing away from me. So I was basically forced to learn as much as I possibly could. So it was a very difficult time in school.

Jo Reed: I'm just curious, when art, when drawing and carving really came into your life in a fairly major way?

Luis Tapia: My early 20s. At that time, I had tried to go to college and of course, I got lost in college because of my dyslexia and anyway, I ended up working at a clothing store and so as a hobby on the side, I started carving and with that, I started to realize my cultural heritage a little bit more, and finding out that the art of New Mexico, the Hispanic art of New Mexico, which at that time was basically Santos, religious images and so I started my hand copying some of the pieces. So that was the beginning of my carving. I was about 22, 23 years old and somewhere in there and of course, I was still working, right?

Jo Reed: And wasn't the Chicano movement very instrumental to you in looking around and seeing what was around you culturally?

Luis Tapia: Oh, yeah. Well, that's sort of what sparked me a little bit because there I was when the Chicano movement was going on and I don't know if people really understand that movement is based on the farm workers out of California, Texas, and New Mexico that were having so much difficult time with the owners of the ranches and so on and there was a lot of protesting going on for fair wages and so on and so forth. Then here in New Mexico, we were having the land grant issues. So there was a lot of demonstrating going on and of course, I'm a child of the 60s and 70s, and I would join in on those on those things. So I would find myself in the street demonstrating. I didn't do it on a daily basis or anything like that. But, I got a little bit involved and, we would be out there saying, Viva la raza, you know, long live the race sort of things and I started to think to myself, well, you know, what about my race? What am I? You know, it brought more curiosity to me as to what I was actually saying, and even though I was living the culture, I didn't know about the culture. Because again, going back to school, all we ever heard about was the pilgrims. Nobody ever spoke about the Hispanic history and we were never taught that. So I started to research that, and that's where I got involved with the art aspect of it.

Jo Reed: I’d like to talk about Santos and what that is and its history in New Mexico.

Luis Tapia: Well, that's a long history lesson there, because we have to remember that the Spanish actually, if I can go back a little bit, entered the Americas in the 1540s, basically and actually, they entered the Americas in 1540, but they'd never reached New Mexico until 1598 and in 1598 is actually when they started the settlements in New Mexico. So, a lot of the religious iconography that came, of course, was Spanish and Mexican, because they had already been in existence for almost 100 years prior to the entering of New Mexico. But in 1680, there was a Native American revolt in New Mexico, and they ran the Spanish out. So during that time, they destroyed a lot of the religious iconography and some of the churches. So it wasn't until the Reconquest, which is in 1693, and resettlement of New Mexico by the Spaniards, that they found that the religious iconography was all destroyed. So the Hispanic people started making their own religious images, which were very primitive. So it developed its own style here in New Mexico. It's very unique to New Mexico and southern Colorado. it became a folk art and that's the basic history of the Santo.

Jo Reed: And who is the Santero?.

Luis Tapia: The Santero's the name given to the maker. He's actually the maker of the Santo. And I did that sort of imagery for many, many years, about 10, 15 years. I was specific in the religious aspect of it.

Jo Reed: Now we're back to your history. So what drew you to carve religious images? What drew you to Santos?

Luis Tapia: Well, again, it was re-educating myself to my own culture, right? And finding out the religious meanings to all these pieces. I had been going to church with my grandmother and my mother, and they had us kneeling on kneelers, and I would see all these images, but didn't know anything about them. So little by little, it was a lot of research work to get involved with that sort of imagery and as I started to develop carving them, I found I would be giving them away at first, right? Because I was just in the beginnings of my year and then after a while, I came to the realization, well, maybe I'll try selling a couple of these things. So we started selling them, and eventually I got involved with what's called the Spanish Market in Santa Fe, which is a market devoted to the historic preservation of the New Mexico arts, which would involve anything from tin work to furniture to weaving and so on and so forth and that got me started on my professional quest.

Jo Reed: Now, what are the elements typically used or traditionally used in these sculptures?

Luis Tapia: The traditional woods that are used are cottonwood root or a cottonwood tree, aspen, and sometimes pine. It was just whatever was available to that specific artist, because the New Mexico and Colorado terrain changes from one end to the other. So, after the piece had been carved, then they would use what's called gesso. It's sort of like a paint plaster to apply to the piece. So, it covers up all the seams and gives you a good base for color and the colors that were used in historical times, of course, were natural dyes. They were painted over with natural dyes and then they were varnished with a tree varnish at that time. So that's the traditional way of doing it and that's how I originally started was with the help of the Folk Art Museum in Santa Fe and their curators there teaching me the process of a lot of these things. I started doing my pieces like that. But I then found Hobby Lobby (laughs) and it was a lot easier buying acrylic paints. So I started a little bit by changing the whole aspect of paint and to my discovery, you know, originally all the New Mexico Santos are very dark and again, it was because of this varnish that had been applied over the top of them and over a couple hundred years with candles burning and so on and so forth, the varnish darkened. So, in my research, and I was able to deal with a lot of the old images and cleaning them and so on and so forth, I found that the colors underneath were very, very bright. So that's what pushed me into acrylic colors and I started using the brighter colors in my work, which later on ended up to get me thrown out of Spanish market.

Jo Reed: Wait. You were thrown out of the Spanish Market for using brightly colored acrylic paints? Tell me about that.

Luis Tapia: Well, it's that I only showed there for possibly about four years, I think at the very most, and I started not only doing that, but I was experimenting with imagery. So their idea of the imagery is they only wanted pieces that were specifically devoted to historic New Mexican arts . So I started experimenting a little bit and I did like a Noah's Ark at one time, and I did the Last Supper and those were not looked on very highly by the people running the Spanish market. So what they ended up doing was telling me either do what we want you to do or you move on. So I ended up moving on.

Jo Reed: And you continued to create work that was brightly colored, but also you began creating work that was actually depicting the world that you saw around you and incorporating that into religious imagery. How did that evolve?

Luis Tapia: The actual process of that whole deal is that I would research my work prior to, you know, in other words, if we were going to do a Saint Francis, for instance, I would pick up the books, holy books and read about Saint Francis. So I knew exactly who I was dealing with or if I was dealing with a crucifixion and so on and so forth. And little by little, I started to find that all these images had social commentary involved in them. So, in studying all these saints and then being involved with the movements that we were going through in the 60s and social commentary, I came to a place in my head saying, well, what if Mary and Joseph were here today? Who would they be? What would they be? How would they look? And so on and so forth. So I started doing it into my pieces. I started making Mary and Joseph pieces that would relate to the people, the young kids of today. They were just, you know, regular street people. So that's how that imagery started to develop little by little.

Jo Reed: You know, it's not dissimilar to liberation theology, is it?

Luis Tapia: No.

Jo Reed: So Luis, you're at one time, you're honoring the cultural and historical roots of Santos and you're also innovating and pushing the boundaries of it at the same time.

Luis Tapia: Well, a lot of my feeling towards that is, you know, because of the way I was treated at the market and so on and so forth and the market proceeded for many, many years with those same rules and regulations. To me, it was a suppression of expression-- for a person to have the ability to express himself with his hands through his work, right? And so I pushed a little bit harder and harder as the years went by and my social commentaries became bigger and bigger. And, you know, I started to deal with, of course, social issues and political issues and also religious issues. I did pieces that were dealing with the pedophilia issues of the church and that didn't go over too good with a lot of people, but I was coming out with how we were living today and the issues that we were dealing with today.

Jo Reed: And you're creating these pieces and people, and many of them are populated with everyday people, as you said, people you would see on the streets and they're seeing themselves reflected in sculpture that was traditionally reserved for saints. That had to have been quite a moment for them. I mean, for you and for them, it's a real gift.

Luis Tapia: Well, it caused some issues, especially with a lot of the older folk. And, you know, again, getting back to the full religious aspects of New Mexico is very, very Hispanic religious people, right? And they were very devoted to the church and when I came out with this imagery, it definitely shook them up a little bit. But little by little, it got easier and easier and it took many years before, you know, other artists started to get that idea and to try to experiment themselves because they saw what had happened to me and of course, a lot of these artists that are doing it at that time, you know, were needing the financial help of their work. So they weren't willing to jump into the pool as of yet, right?

Jo Reed: Yeah and how was that pool financially for you?

Luis Tapia: Well, I started doing all right. But, you know, when I got thrown out of the market, that was it. And I already had two kids on the ground at that time and I had quit my job because I was being, I was selling my work. So when that went, that meant that there was a lot of financial issues that were coming up, right? So I had to find a new outlet to work and in Santa Fe, even though we have a lot of art galleries, they were not open to Hispanic art of that type for their galleries. So nobody was selling Santos or things like that in all the galleries in Santa Fe. So I had to find another alternative and I started dealing with these markets that were across the country. I did a market in Utah at the American West Show that they had there. I did some in Texas, in Colorado and little by little, my name started getting out there through these markets and in one of the markets, I met a woman who I don't know who she is today, her name, but I just remember her talking to me and she says, you should be in the Smithsonian and “Yeah, that would be great.” That would be great. Well, apparently she had some connections at the Smithsonian and years later, they invited me to the festival, their Bicentennial Folklife Festival and I went there with my images, and that helped a great deal, right? And then they also collected my work. So that's, that was the beginnings of being accepted for what I was doing.

Jo Reed: Well, we talked about how you blend the tradition of Santos with your own creative expression and I'd like to, if you don't mind, discuss a specific piece that illustrates this is so listeners can get a visual sense. How about “Two Peters Without Keys? This is a piece that depicts two heavily-tattooed men in a prison cell. Give me a little background…

Luis Tapia: Well, that, well, we all know who St. Peter is and he holds the gates of heaven. He has the keys to heaven and his imagery in the Catholic Church is him holding the keys to the heavenly gates, and I started to think about people that don't have that opportunity and I thought about the gangs and the people in the penitentiaries, and I did the piece based on them, and using also religious iconography on them as tattoos, and that was created in the penitentiaries. The religious tattoos were a big thing in the penitentiary. They would put big images of Our Lady of Guadalupe, for instance, on their back, and these were actually meant as shields to protect them because most of the guys in the penitentiary were Hispanic and they were raised Catholic and very traditional Catholic. So they still respected it at that time. I'm talking about the 70s and 60s and so on and so forth. So they would not cut a person through the tattoo of Our Lady of Guadalupe, right? Or Our Lady or the Virgin Mary and they would put images of the Christ figure being crucified on their chest so they wouldn't get cut there. So these things were actually used as shields. And I did the two pieces and they're heavily tattooed with penitentiary tattoos and of course, these are two Peters without keys, as you can see that they're behind bars. And if you go to one side of the piece, you're in there with them, and if you go to the other side of the piece, you're outside looking at them.

Jo Reed: And that's the other innovation you brought to the art form is insisting on this 360-degree view. They're meant to be seen from all sides.

Luis Tapia: There's a lot to speak about, all the way around my pieces and believe it or not, where that imagery developed itself was me studying Henry Moore's work. I don't know if you're familiar with Henry Moore.

Jo Reed: Yes, I am. I love his work, actually.

Luis Tapia: Yeah. And it's very contemporary, very abstract work and you're probably saying, how does that relate to you? Right. Well, it did and it made me think of how Henry Moore, you had to go around his pieces to get the full impact of his work. And at that time, all the pieces that I was doing, they were meant to go up against a wall and so you were losing the sculptural beauty of the piece if it's flat up against the wall. So I started to make my pieces where you had to go around them. So not only were there statements in the front, there would be statements in the back and that also made the viewer study my work more, to get more involved with my work.

Jo Reed: Your work has really a unique ability to tell stories and capture emotions and evoke emotions in viewers. Can we talk about your creative process and how you translate your ideas into three-dimensional forms? Tell me how you work. How do you begin a piece? How much is thought out before you start to pick up some wood?

Luis Tapia: Well, I generally start with some sort of an idea that I want to express, whether it be a social comment that somebody might have said something, or a political comment that might have come out and that gets me started, just thinking about that. And then I have to think about, is this a man, woman, or what kind of image comes out here? So that's when you pick up the piece of wood and you start carving this wood, and I develop like a relationship with this piece. So I'm asking myself, who are you? What are you? Where do you come from? What do you look like? And I search for that individual in that wood and it starts to develop. It starts to take form. So it's this conversation that I have with the material and as I work along, more things start to come into the piece. Well, what is this man holding? Why is he holding that? How do I interpret that piece into what I want to say? And so it becomes a development and these pieces can take months to finish, and they're not huge pieces. They're approximately anywhere from 18 to 24 inches high. So they're not very big. But it takes me a long time to develop the whole piece and I could be working on possibly two to three pieces at the same time, and they're all in different stages. So that if I run into a problem, and I get into an argument with the piece, well, then I can move on to the other one and then I can get it back to the original piece. So it's a development that happens between me and the wood and I don't even know what the end result is when I start. I have never been able to do a piece that I knew exactly that it was going to come out the way it did.

Jo Reed: You've mastered painting as well. A lot of your work is so intricately painted. Your altars, your reimagined ofrendas as lowrider dashboards, for example. The painting is really amazing.

Luis Tapia: Well, thank you so much. I never considered myself a painter. I feel very guilty in using that term with myself, because a lot of my friends are incredible painters, and I work real hard at it. That I got to tell you, and it's a whole other different expression when you're doing sculpture, which is three-dimensional, and then you start painting on a flat surface, and you're trying to get that dimension out. So it's a lot of work for me, and the dyslexia doesn't help that at all either. But it's a workout. But thank you so much for thinking that.

Jo Reed: No, not at all. I want to talk about the dashboard pieces, because I've never seen anything like them. They are wonderful. They are so interesting. They're humorous. They're thought-provoking. They are carved out of wood and intricately painted. They are altars reimagined as lowrider dashboards. How did you develop these and then explain how they're so culturally specific to New Mexico.

Luis Tapia: Well, the way that imagery developed is because of my mother. My mother had this 56 Ford that she trucked along in, and of course, on the dashboard, there was every saint in the world on the dashboard. These little neon little saints that were with the magnets that would stick onto the dashboard, and there was always a rosary or a scapular hanging from the mirror. So that's my whole vision of a car, you know, growing up, was all these images going down the road. And so it stuck with me for a long, long time and then, of course, here in New Mexico, as well as in other states, the lowrider was a very important art form that had been developed over the years here. And the thing that made them really different from all the other lowriders from around the country is there was a lot of religious iconography that was painted on the cars. So you saw a lot of the cars. On the hoods, there would be Our Lady of Guadalupe or the Sacred Heart pieces. So I interpreted it into these dashboards and then I made the scenery, when you're looking out the window, most of them are of New Mexico landscapes. So, it makes you feel like you're cruising out yourself, right?

Jo Reed: You know, your work just invites viewers to engage in conversations about culture and about identity and about tradition. I'm assuming that's your hope, that your work inspires both reflection but also conversation.

Luis Tapia: Well, that's very true. And, you know, a lot of times when I'm doing speaking engagements and things of that sort, and when I'm trying to explain my work, I stop in certain places, because I don't want to give the whole story up. I think that's up to the viewer to deal with and that's another reason why I do pieces in the round. So there's more commentary when you go around the piece and it starts to tell you a story and you're trying to search for this story and you're trying to make sense of what I'm trying to say. Now, in a lot of my images, like the ones that are social and political commentary, I don't have answers for a lot of those problems. I do not have answers for them, but I do have questions and if I can get the viewer to realize those questions, I think that's great. I've accomplished my job and if I can get people thinking about these things more and seeing a different way, possibly it'll get better down the road.

Jo Reed: How long do you spend in the studio per day? Do you try to work every day? How do you do the actual working with wood or painting part?

Luis Tapia: It's seven days a week, at least five hours a day and that's constant. Unless we got something to do or, you know, something comes up. That's but every day it's at least five hours and it's a discipline that I've had for 15, 20 years now.

Jo Reed: You also bring a lot of humor to your work. The dashboard altars and you have one piece that I really need you to talk about that's quite different from the others called “A Slice of American Pie.”

Luis Tapia: Oh, the Cadillac?

Jo Reed: Oh, yeah.

Luis Tapia: That was one of those things where you say to yourself, what was I thinking?

Jo Reed: I have many of those. “A Slice of American Pie” is a Cadillac Coupe de Ville cut down the middle length-wise and you’ve intricately painted it with Chicano and New Mexican iconography. You know I’m going to ask: how did this come to be?

Luis Tapia: Well, again, going back to, you know, me being inspired by the lowrider and the car imagery that I had been grown up in and, you know, seeing all these cars and I thought of I've always thought of the lowrider and even before that these are pieces of art. Now they're accepted as pieces of art, but in the early days they weren't. But anyway, I wanted to produce a piece that would respect the lowrider as a piece of art. But I didn't want to do a whole car and then, you know, I thought about how would you hang a car in a house or stuff like that. So this thought stayed in my head for a while and I was at a friend's house. He's a master welder and we were sitting out there having a couple of beers and we were just talking and having a couple more beers and still talking and then this thought just came into my mind with him after a few more beers. I says, “Bill, could you cut a car in half? “ And of course, Bill's had as many beers as I have. He says, “hell yeah.” So I said, “well, I was thinking that maybe cutting the car in half that I could hang it on the wall.” And he says ,”I could make that happen. He told me and I and he says, in fact, I have the car for you.” And we went out in the back of his shop where he has metal workers always collect metal, man. They have cars, they got junk and stuff like that and there's this Cadillac out in the field. I mean, it was trashed. It was totally trashed and he says,” I'll sell you that thing for $500 and we'll work on it.” So that's how it started. It took me over a year, a little over a year to build, do the whole thing and I had help from Bill and my son, Sergio, and my grandson, Andres. So it was only the three of us and I, of course, was putting more of that most of the time into it. But you had to learn everything. I had to learn metal work and I had to learn body work. I had to learn how to spray paint. I mean, it was amazing. And the piece is a story about Santa Fe, basically and again, I used the tattooing imagery. That's the reason the color is blue in the piece. It relates to the tattoos that were coming out of the penitentiary and the painting style, if you will, is more of a penitentiary ink style, as they call it. So that's the basics of that piece. But it was a physical struggle.

Jo Reed: I bet it was.

Luis Tapia: And that piece can actually be hung. It was actually meant to be hung, but we ended up selling it to the state of New Mexico and it's on permanent exhibit at the Spanish Cultural Center in Albuquerque and they have it on the ground, which is cool because it really shows a lowrider aspect to it.

Jo Reed: You bring so much humor to your work. You have to be doing this on purpose. Your titles are puns and at the same time, you're also dealing with serious issues. How does humor work for you?

Luis Tapia: It makes things easier, makes the pain easier, somehow. You know, with every sorrow, there's also a smile, you know, somewhere in there and I try not to take myself so serious. I think that could be a problem if I were in some of the pieces that I work with. But I like people to enjoy my work. I like to see them smile. I like to see them cry. There's people have cried seeing my work and then they turn the corner and you'll see them smile because they saw another aspect to the work that they didn't see before. So, if I can draw emotions out from people, I think it's great and even if they're bad emotions, even if they're pissed off emotions, I think that's saying a lot for my work, that I can pull feelings out.

Jo Reed: Right. Indifference is deadly.

Luis Tapia: Right.

Jo Reed: You know, you've also created altar pieces for local churches and I wonder if you approach this work at all differently.

Luis Tapia: It is impactful because you have to get involved with the community. Whereas in my regular work, I don't get involved with anybody but myself. And with these pieces, you get yourself involved with the community. You meet with the community. You talk to them and you're taking a great deal of responsibility in doing these pieces because these are pieces that these people have to live with, their religious life with, and for me to try to capture that for them is a challenge. So it's a different approach for sure and I haven't done very many, but the ones that I have done have been respected very highly. So that's a good thing.

Jo Reed: Can we talk about a little bit deeper, you're incorporating subject matter that can be provocative into sculptures while still maintaining a really respectful engagement with the traditional style. But then I also want to talk to why you think Santo is receptive to that kind of incorporation.

Luis Tapia: I think what it's all about is when I started to research some of the religious images, and I started to find this commentary back there. But we don't see it. We like to look at these saints and we see their holiness, you know, their spirituality type of thing. But in fact, what I'm trying to do is show more inner structure to that individual, how he lives and why he lives. But I use the traditional method to explain that and the history is very important to me as well. You know, Hispanic history is very important to me. So that's why I stay with that imagery and that style of imagery, because it's my foundation. It's how I grew up. It's the whole basis of my culture as well.

Jo Reed: I think so often we think of tradition as something that's static in the way we think of saints as something that's static, you know, and not as, you know, a living, breathing thing. I mean, for culture to have an impact, it has to be alive.

Luis Tapia: Exactly. You know, and that's, you know, when I was a little child and I would see these images on the wall, that's what I would see, you know, or there would be a fear factor involved, too, when you're a little guy, you know, you look at these things and they're kind of scary, you know. I wanted to say more than what was in my mind as a child. I wanted these pieces to have conversations with me and with you and with everybody else. So that might be why my style is what it is.

Jo Reed: Correct. You have been named a 2023 National Heritage Fellow. You've gotten many awards throughout your life, Luis, but now you're a National Heritage Fellow.

Luis Tapia: They're telling me something. They're telling me to retire.

Jo Reed: You think so? I wonder what the award means to you and also for the work that you do.

Luis Tapia: Oh, it means a lot to me. You know, but there's two awards in this whole thing with that. You know, the award of the people that backed you up, that turned your name in, that sent in the letters to the council, that's an award all of its own, you know, that you have these people that I didn't even know this was going on and that they were backing me up like this. That's an award in itself and I take great pride in that because that says there's a lot of respect. And of course, the respect that the National Endowment gave me with this award is incredible because it's a life achievement award and it credits me for the change of or the creating of a new style of work that has been developing slowly in the last 30 years, where a lot of the new, if you will, Santeros, are seeing my imagery and dealing with that imagery and bringing it out themselves in their own work.

Jo Reed: And I bet if you go to the Spanish Market now, you'll see brightly colored…

Luis Tapia: Oh, it's incredible. You know, when I started, there was only like 30 of us at the market, and that included weavers and tin workers and Santeros. Today, there's like over 300, and the colors are brighter than hell. And I think there's a lot of artists out there that don't even know who I am, but they're doing stuff that was inspired by me, you know, like car imagery or different ways of approaching a saint and they might not even know who I am, but that's the gratifying part about it, you know, that this is happening.

Jo Reed: Yeah, it has to. I mean, you wanted to express a deeper way of grappling with this art form and by doing that, you've really transformed it.

Luis Tapia: Well, you know, even the old traditional Santos were very primitive, very crude, and some had some major expressions, but a lot of people didn't realize that these guys were actually manufacturing these pieces out of their houses. You know, there was a story when I was first starting out that they thought that the Santeros was this guy sitting by his fireplace with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on the wall and carving this holy piece and that's not true. You know, these guys are trying to make a buck, and that was an outlet for them to carve these religious pieces. So a lot of them don't have like a lot of expressional feeling to them, right? But I think that what I've tried to do is bring that out more and make these things have feeling.

Jo Reed: And those of us who are looking at it have feelings too, and thoughts. Your work is magnificent. It really is.

Luis Tapia: Well, thank you.

Jo Reed: You're welcome and many, many congratulations and I look forward to meeting you in September.

Luis Tapia: Oh, are you going to be there?

Jo Reed: At the ceremony. I'm definitely going to be there.

Luis Tapia: Wonderful. Okay. Well, that'd be pretty cool.

Jo Reed: Yeah, that'll be great.

Luis Tapia: I'm looking forward to it. For another reason, is that I understand that Little Joe and La Familia...

Jo Reed: I was going to ask you if you knew Little Joe…he’s my guest on next week’s show!

Luis Tapia: Well, I've been listening to his music since, oh God, I don't know, I guess since he begun, right? And he would come up to New Mexico and he would play all around New Mexico and so I am so looking forward to meeting him, because he has definitely been a musical inspiration to me.

Jo Reed: Oh, that's wonderful. That's wonderful. That's so nice to hear. That's why I think this is going to be such a wonderful event.

Luis Tapia: We're looking forward to it, that's for sure. Not looking forward to the travel, but I'm looking forward to the ceremony.

Jo Reed: Luis, thank you for giving me your time and thank you, because I know you're going to hit the studio for five hours, so thank you.

Luis Tapia: Yeah, I'll be going right there right after I talk to you.

Jo Reed: I appreciate it, and I hope you have a great day.

Luis Tapia: Well, thank you, Josephine, and you enjoy the rest of your day.

That was sculptor and 2023 National Heritage Fellow Luis Tapia. Give yourself a gift and check out his work at Luistapia.com

And I will see him on Thursday September 28 and Friday Sept 29 and you can too. That’s when the NEA will honor the most recent class of heritage fellows; and, since it’s the first in-person Heritage Fellowship events since 2019, we’re bringing them together with the 2020, 21, and 22 fellows for a celebration that explores the legacy and impact of this lifetime honor.

On Thursday, a special afternoon panel will feature a film screening and conversation about Native art-making and the land, co-presented with the National Museum of the American Indian. National Heritage Fellows will share firsthand stories of place and belonging as understood through their life’s work as traditional and community-based artists.

And then on Friday there’s the National Heritage Fellowships Awards Ceremony, hosted by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. The ceremony will open with a performance by Irish flute player and 2021 NEA National Heritage Fellow Joanie Madden.

The events are free, open to the public and also available through a live webcast. You can find information about it all at arts.gov/heritage.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced by the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts, leave us a rating and tell your friends! I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.