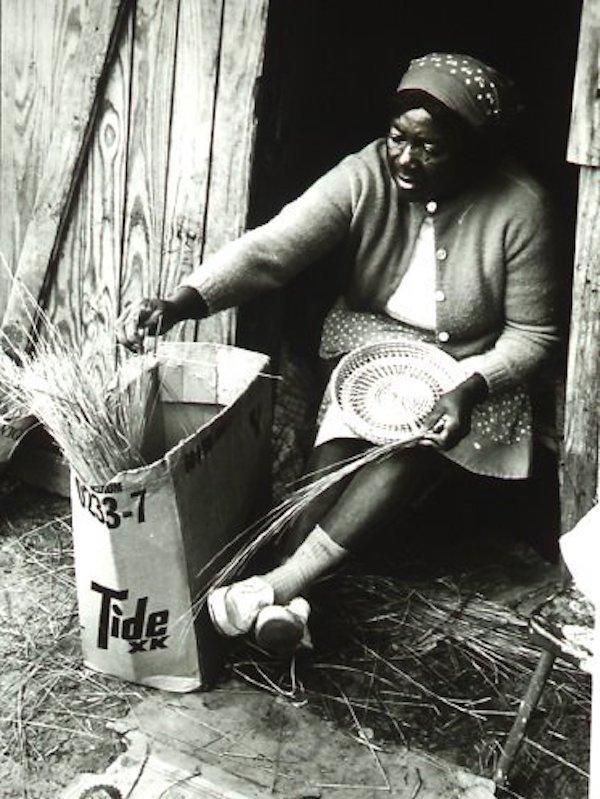

Mary Jane Manigault

Photograph by Dale Rosengarten, Courtesy Folklife Resource Center, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina

Bio

Mary Jane Manigault was born June 13, 1913, outside Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, north of Charleston. Growing up, she learned about the tradition of coiled basketry from her parents, Sam and Sally Coakley. "My mother taught me how to make baskets when I was eight years old," she said. "I made a hot pad, made it out of sweetgrass, palmetto, and pine needles for color."

The craft of coiled basketry has been practiced in the sea islands off the coast of the southeastern United States since the late seventeenth century, when it was brought over by African slaves. At that time, European colonists in the Carolinas were trying to establish agriculture in the coastal wetlands and experimented with the growing of rice. Unfamiliar with the proper cultivation techniques, the European settlers depended on the knowledge of the enslaved Africans, who were experienced in tropical farming and who introduced specialized agricultural practices and tools, including various kinds of work and winnowing baskets.

The earliest baskets were made for field use. Stiff bundles of bulrushes were tied together with strips of oak, hickory, or palmetto butt in a coiling technique to make produce baskets and what were called fanner baskets. Produce baskets were large and round, with high sides, and fanners were wide, circular, shallow trays, about two feet in diameter, and used to winnow rice after it had been hulled.

Although the use of field baskets declined during the nineteenth century, domestic basketry flourished among African Americans. Over time, basket makers slowly modified the old styles, and the range of sizes, shapes, and decorative motifs increased. Among the styles that continued into the twentieth century are clothes baskets, church collection baskets, sewing baskets, picnic baskets, traveling baskets, hot pads, and bread trays. The methods for making baskets has essentially remained the same, though the styles themselves have become more individualized.

For many years, Manigault sold her baskets in the open-air Market Square in Charleston. Often she had 30 to 50 coiled grass baskets on display at any given time. She liked to demonstrate and explain her techniques to interested shoppers, as she twined narrow palmetto strips around bundles of sweetgrass and pine needles. As the basket ages, she said, the pine needles turn brown and contrast with the gold and yellow of the other fibers.

Manigault's baskets have attained widespread recognition because of the sculptural quality of the forms she created and the imaginative use of natural design and color. She often experimented with different forms, but never overdecorated, understanding the value of the plain, unadorned traditional designs. Throughout her life, she was an exemplar in her community, teaching children and anyone interested to make baskets. She believed in "good, honest workmanship." In December 2000 she suffered a stroke, but said, "I'm going to keep making baskets, as long as I can."