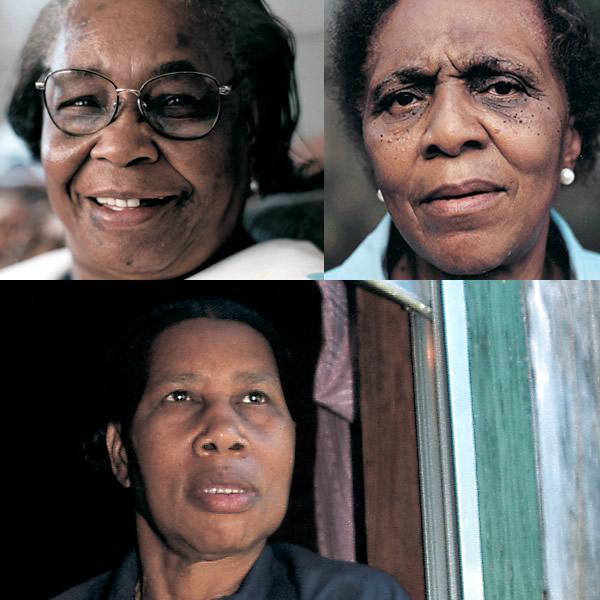

Mary Lee Bendolph, Lucy Mingo, and Loretta Pettway

Bio

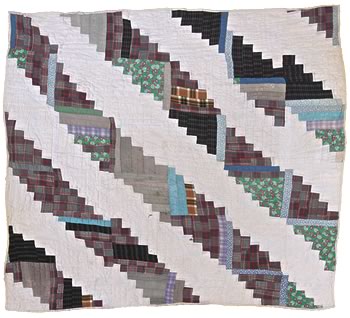

The community of Boykin, Alabama, known to many as Gee's Bend due to its proximity to a bend in the Alabama River, is home to some of the most highly regarded quiltmakers in America. These include Mary Lee Bendolph, Lucy Mingo, and Loretta Pettway, three of the chief quilters from the oldest generation of quilters who represent this profound cultural legacy. Described by the New York Times as "some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced," the quilts are known for their improvisational and inventive quality, often being compared to 20th-century abstract paintings.

Mary Lee Bendolph, born in 1935, learned to quilt from her mother. She split her time as a child between working in the fields and attending school. While quilting, Bendolph prefers to use fabric from old clothing to avoid wastefulness, and her style of quiltmaking tends to mix geometric shapes, like rectangles and squares, with abstract designs.

Enlarge

Loretta Pettway, born in 1942, made her first quilt when she was 11 years old with guidance from her grandmother, stepmother, and other female relatives. Pettway tends to use the bricklayer pattern in her quilts, which resembles a pyramid or set of steps. Two quilts by Loretta Pettway and one by Mary Lee Bendolph were in the group chosen for the U.S. Postal Stamp Collection issued in 2006. Today, paintings of these quilts are part of the Quilt Mural Trail, leading visitors around the cultural and natural landscape of Gee's Bend.

Enlarge

A homemaking educator who was born in 1931 and worked for the extension service for more than 20 years, Lucy Mingo has served as a leading quiltmaking instructor, mentoring apprentices and students all over the country. In 2006, Mingo received a Folk Arts Apprenticeship grant from the Alabama State Council on the Arts to teach quiltmaking to her daughter, Polly Raymond.

Enlarge

The quiltmaking tradition of Gee's Bend dates back to the early 19th century when female slaves used strips of cloth to make bedcovers. Gee's Bend's quilts were first noticed nationally in the 1960s when the women were members of the Freedom Quilting Bee which was organized during the Civil Rights movement to help produce a much-needed income stream into the community. The quilts made by the quilting bee were sold throughout the U.S. In the early 1980s, the staff from the Birmingham Public Library revisited the area as part of a photography and oral history project. Mary Lee Bendolph, Lucy Mingo, and Loretta Pettway's quilts have been on exhibit all across the nation, including exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Interview with Mary Lee Bendolph and Lucy Mingo by Josephine Reed for the NEA

September 30, 2015

Edited by Holly Neugass and Liz Auclair

LEARNING TO MAKE QUILTS

NEA: Who taught you how to make quilts?

MARY LEE BENDOLPH: My mother taught me. She started me off piecing quilts. I wanted her to let me piece quilts with the machine but she wouldn’t do that. She gave me a needle and some little pieces. Well, we had nothing to start making the quilts with because at that time we didn’t have much clothes and things.

LUCY MINGO: My mother taught me how to make quilts. I started making quilts when I was 14 years old. She would sit up by the fireside at night and make quilts, and I said, “Mama, teach me how to do this.” I thought it was fun just to sit down and get in there and make quilts. The first quilt I made was crooked. She said, “Uh-uh, you’ve got to do better than this. You can’t have a crooked quilt.” Well, I kept on and kept on until I was taught how to do it real well. I make quilts real well now, and I thank God for it.

NEA: Can you tell me about the tradition of using material from old clothes for your quilt?

MINGO: Just like this shirt I got on. Now, the front of this shirt is worn out but the back is good. We always got the back. And just like these pants I got on, the front would be white but we [could] always get from the back. We used what we had. We weren’t able to buy material like we’re doing now, but we still made quilts.

NEA: How long does it take you to make a quilt?

MINGO: If it’s not a fancy quilt, I can make it in a day-and-a-half. But on a fancy quilt, you know, you can’t sit there and sew every day. You sew so much each day. It would take me about four days to do that. But just a regular quilt it doesn’t take me that long.

NEA: And that’s just for the top of the quilt?

MINGO: Just the top. But when you make the quilt you’ve got to get a lining. And when you get the lining, it’s got to be a little larger the quilt top. Then when you get the lining, you’ve got to buy the cotton. But we didn’t have to buy cotton. We always picked cotton from the field. And my husband would save me two sacks of cotton every year. Then you get a stick and beat the cotton out very thin and spread it over the quilt. When you get it on the quilt, that’s the line that you put it on first. Then you put the top on second. Then you put a frame on this side and one on that side and one crossed and another one crossed. Then you tack the quilt on that. You’d bring the quilt down every day and sit there and quilt the quilt until it was time to get the lunch ready for the kids to come from school. Then you roll it back up in the top of the loft. When the children came home, they had to study their lesson. You couldn’t get it done until they got back to school, and that’s the way I did it.

NEA: Now, when you started you were quilting by hand. You didn’t sew with a machine, is that right?

MINGO: We didn’t quilt with a machine.

BENDOLPH: No. They wouldn’t let you do it with the machine. No. That was Mama’s; that’s hers. And she would give me some things to sew with, but she’d never let me use that machine. That’s what I really wanted to do. She said, “No, you’re not supposed to sew on my machine.”

NEA: Do you remember the first time you did a quilt on a machine? Was it like, “This is so easy?” Did you feel like you were cheating?

MINGO: I felt like I had to do it right, because if I broke Mama’s machine I know she would never let me get on it again. And so I took my time and sewed slowly, not too fast. When I got my quilt finished, I told my mother— I said, “Mama I’m finished with my quilt.” She came and looked at it and she said, “You did a good job this time.” And from then on she taught me how to sew on the machine.

BENDOLPH: Well, Mama still wouldn’t let me stay on the machine. If she wasn’t at home I got on the machine and sewed while she gone. I told you I was already smart. And then if I thought she was going to come back, I put the machine back and got out of the way. I didn’t tell her a thing but she just knew exactly what I did. She said, “The next time you do [that], I’m going to give you a whipping.” I didn’t borrow it no more until she gave it to me to let me to do it. I wouldn’t do no more on my own.

NEA: When you were younger would you plot out the pattern of the quilt before you started sewing? Or did you do it as you went along?

MINGO: I wasn’t making any fancy quilts. I was just making string quilts. You get this long strip and sew it together. You get another long strip and sew it together, and you did that until you got the quilt all over the bed. We were just making string quilts at that time. The first quilt [my mother] taught me how to make was a Z, and a Z was very easy to make. And she said, “You got it, and I’m going to turn you loose and let you do it. You’re on your own.” That’s what I did, and I started doing them on my own because I had a lot of children. I had to make quilts to keep them warm.

NEA: And what about you, Ms. Bendolph? When you were young did you plan out what you were going to do? Or did you just let the cloth tell you what it was going to do?

BENDOLPH: Well, I didn’t have anything to do. I just used what little rags I could find. My mama had 17 children. We didn’t have big material or nothing. The only thing I had was the rags I wore. And I knew it wasn’t going to be very good, but when I made them they were beautiful to me.

NEA: When did you start really doing patterns?

MINGO: I started doing patterns after I was married for a long time. I used to go to the Quilting Bee and do a little work, but it wasn’t very much because I was in the lunchroom in Boykin High School. I would watch other people’s patterns. I had a mother who could make [a quilt from] anything you drop on the ground. And I would go to her house on Saturdays and be around there watching her make quilts. And once I began to make quilts, I said, “Mama, I want to make quilts like you.” She said, “You do?” So she came down there one Saturday, and she got on the machine. She said, “I’m going to cut your pattern out,” and that was a Z. And she started from there. And from there on I just went on doing my own thing. I can make any kind of quilt. I made one that’s got 23,580 pieces in it.

NEA: So during that time when you were quilting, when were you able to go out and buy material and decide on a pattern before beginning? What was that feeling like?

MINGO: It was fantastic for me because I loved to sew. And when I could buy material to make quilts, I just went crazy buying material and making quilts. I made lots and lots of quilts.

NEA: Were you in Gee’s Bend during the Freedom Quilting Bee? Can you tell me a little bit about that, Ms. Mingo?

MINGO: Well, I worked at Freedom Quilting Bee for a long time. A guy named Francis X. Walter, he got together the ladies who he thought could do a good job of quilting with Estelle Witherspoon. Mary Lee Bendolph and a lot of people from Boykin were there, and I was from Boykin too. And we all worked and worked and worked so we could get paid. We began to get paid. We worked a long time without any money, but when the Lord blessed us we began to get paid. And I got a job at the school. I quit working there, and I began to make my quilts at home. And when I always made them I sold them at the Quilting Bee.

RECOGNITION AS AN ART FORM

NEA: Quilts are so practical. You make them because you want to keep your family warm. You give them as gifts to family but they’re for use. And then somebody comes along and says these are art. What did you think when you were told that?

MINGO: Well, I’ll tell you, with the work I had put in mine, I knew it had to be something because we made rows by a finger. And we quilted the stitches so you could hardly see them. We would do that from about ten in the morning until about 2:30 in the afternoon. See, when the children went to school, then you started quilting. And by the time you had to get their dinner ready for them, you had to stop. And so we’d do that [everyday] because we didn’t have anything else to do. Later on down through the years I got a job.

NEA: In the late 1990s, William Arnett came to Gee’s Bend and suddenly your quilts were exhibited in museums in Boston, New York, Houston, Philadelphia… and I’m only naming a few cities.

BENDOLPH: Yes, I sold four. And they were all I really had. And then I started making better quilts because people started bringing things home. It was 2001 then, and that’s when I made so many quilts. I enjoyed it.

NEA: Well, did you go to any of the museums where the quilts were? What did that feel like to walk in and see your quilt?

MINGO: I don't know how I felt. I just felt like I was somebody. I had made quilts, you know, and then museums had them. I really enjoyed that.

NEA: Did it make you think about your quilts differently?

MINGO: Yes, I did. What made me think about mine so differently was that I made them, and I was just making them for the kids to sleep on them. When I began to sell quilts, someone always wanted one. I really enjoyed that. And going off on trips, I just enjoyed it to death because I had met so many people and so many people had gotten my quilts. I have quilts all over the world.

NEA: And you do too, Ms. Bendolph.

BENDOLPH: Yes. Yes. I thank the Lord for that. I said that I could do my best, and then when the people came to talk to me about it, I did the best I could. And I thank the Lord that my quilts could be out there in the world where people could enjoy them. And they would tell me how much they love the quilts that I had made.

NEA: Now, do you still make quilts to keep you warm?

BENDOLPH: Yeah, that’s what the quilt is for—to keep you warm. When you lay down, you have the quilt to cover up.