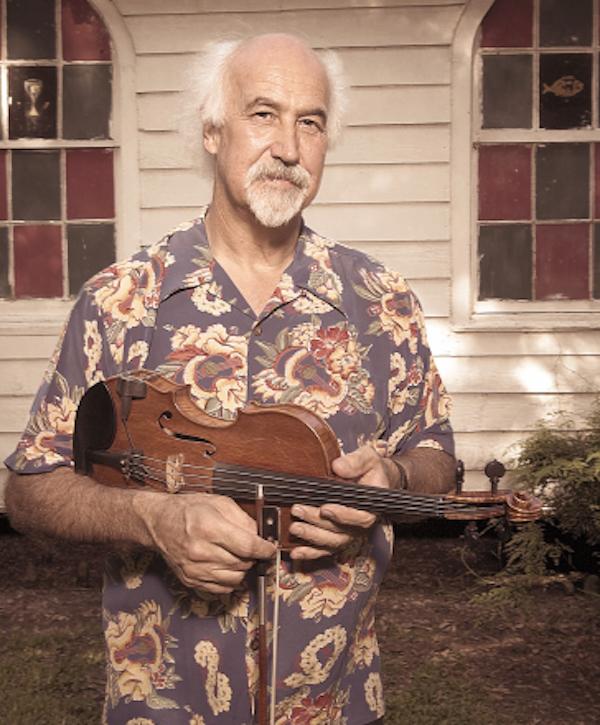

Michael Doucet

Photo by Rick Olivier

Bio

Michael Doucet, fiddler, composer, and bandleader, is perhaps the single most important figure in the revitalization of Cajun music in the United States. Cajun is the shorthand name for the French settlers of southwest Louisiana who were expelled from the Acadian region of Canada in the 18th century. During the first half of the 20th century, both the language and music of French Louisiana seemed to be in decline. Doucet, who grew up surrounded by traditional musicians and storytellers in southwest Louisiana, was more interested in popular music during his teenage years. He studied literature in school, but while playing music at a festival in France in 1974, was exposed to musical antecedents of his own heritage and this inspired him to return to Louisiana on a mission to learn everything he could about Cajun music and history.

In 1975, he applied to the National Endowment for the Arts for an apprenticeship grant to study with and document the master fiddlers of his region. As a result of this project, he was able to learn first-hand from the great masters of Cajun and Creole music with links to an earlier era. Eventually, he formed his own band, BeauSoleil, which is today recognized as the premiere traditional Cajun musical ensemble. With numerous nominations, BeauSoleil's L'Amour Ou La Folie received the 1997 Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album. Cajun music, thanks to artists such as Michael Doucet, is known the world over, and young people of the region are following in his footsteps. He says: "To me, Cajun music really is the heart of our culture. It's not the stomach – we know that's the food. It's music that's the heart. Everybody sings in their own way down here, and that's what keeps us going."

Interview with Mary Eckstein

NEA: Congratulations on your award. Tell me how you felt when you heard the news.

MR. DOUCET: I was very surprised because I thought they only gave it to old people! It's amazing because we played with the late Dewey Balfa when he received the award that first year in 1982.

You know, it's interesting - it's a national award but it really comes down to your community and what you do for your community. I was very fortunate to be around when a lot of people born before 1900 were still alive - the "old-timers," as we call them now. I think that's where most of my inspiration comes from. It's really a process of a continuation - I wouldn't be getting this award if it wasn't for people who came before me.

NEA: When you were first inspired by this music?

MR. DOUCET: I grew up with it. I grew up speaking French and it was no big deal playing Cajun music. All the neighbors played music and everybody spoke French. But it wasn't until I was graduating from high school in the late '60s that I realized that our culture was disappearing with the elder generation, my grandparent's generation. That inspired me to hang out with those people and learn the music. They had more time for us than our parents. They were playing more traditional French music - ballads and older songs that were more popular than what was being played in dance halls at the time. What really inspired me was the connection to France in the early songs.

NEA: And you took a folklore class that had a big impact on you, right?

MR. DOUCET: Yes. In 1969, I took a class at LSU in Anglo-Saxon folklore taught by Dr. George Foss. Dr. Foss and Robert Abrahms wrote the book, Anglo-Saxon Folk Songs. I took the class because I was interested in folk music, and we were going to study things like the Childe ballads, the ballads from the mountains, the blues, Native American music. But there was nothing about Cajun or French or Louisiana music. So, of course, I raised my hand and said, "Hey, what about this other stuff?" And he replied, "Oh, that's just translated from English songs." I didn't think that was right.

So I went directly there to do research. When the Arcadians were deported from Nova Scotia in 1755, most of the written records were burned, so we had no written history. All we had was an oral history as we do oral music. So I was really surprised to find Eileen Whitfield's 1939 thesis on Cajun Creole folk songs that showed me that these were not translated songs. They are our songs.

Lo and behold, she was very much alive and well in Lafayette, the town I grew up in. We became really good friends and she steered me to the research approach. And she definitely instilled in me the bounty and preciousness of our French heritage.

NEA: What special role do you think the music plays in Southwest Louisiana?

MR. DOUCET: It's a carrier. My music has a lot of functions. It's a social function. It's a community function. The music seems to always have carried the history and the soul of our culture. I mean, you know, the food takes care of the stomach. The music takes care of the heart.

NEA: I know that Cajun music has had a bit of a revitalization. Can you tell me a little bit about that and how the broader response to the music has changed over time?

MR. DOUCET: That was a big surprise. In the '70s I was just interested in getting this music back to people in Louisiana, with no thought of anybody else being interested. In 1974 we were asked to play at a festival in France. We were a part of their folk revival and it was then I realized that the interest in this music was broader than I had ever expected. So I decided to take this music out to all 50 states, but on our own terms. Not to present it like country western or the California sound, or any hybrid. We were going to live in Louisiana and be who we are and if people were interested we would take the music out. We were the first group to actually perform in all 50 states in a foreign language and convince people they were listening to American music.

NEA: What do you see as the challenges to continuing to build a broad audience for Cajun music?

MR. DOUCET: Well, it changed a whole lot because it became commercialized in the '80s. The main thing is to not forget the origins, the roots, and the fact that at the core it has nothing to do with making a living. It's about being part of your own life. That's where I learned the music. I learned from people playing in their kitchens. People playing in their houses. Not people performing out. It's not an MTV kind of culture. It's a culture that comes from within. The point is to play from the heart, which is easy to say but hard to do because there's so much history. The challenge for young people is to do the research, to see where we've come from. There were no paths in America before we came here. We created our own roads and never veered from them. We continued to sing in French and to maintain the traditional instruments, not only from the Arcadian culture but from our nearby Creole and Cajun cultures, and from all of Louisiana. The music in New Orleans, as you know, is a hybrid of jazz, classical music, the Delta blues and swing. All of that is incorporated into our music because that's how we grew up.

NEA: What does that mean to you that young people in Louisiana are following in your footsteps and demonstrating some cultural pride ?

MR. DOUCET: I think it's wonderful because everything has been totally Americanized, you know, with television. This is something else. This goes back to a different time. We used to call this old people's music because it was the old people that played it. It's wonderful to hear young people play it and get very energetic about it. And I'm very excited that people are putting some creativity into it, putting their own personality into it. It needs to keep changing, so whatever they do is fine with me.