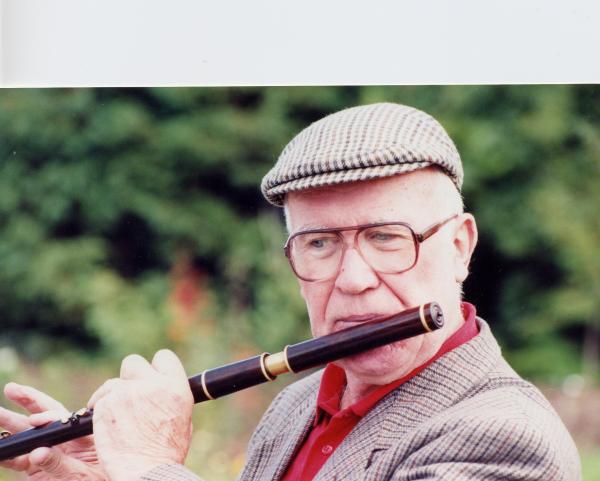

Mike Rafferty

courtesy of the artist

Bio

Born in 1926, Mike Rafferty grew up in Ballinakill, East Galway, Ireland, on a 12-acre farm. In the heart of a locality steeped in the very best of old-style traditional music, he learned to play music from his father, Tom "Barrel" who played flute and uilleann pipes. Rafferty learned many of his music skills in the old way, by listening over and over again to the music played in his locality by master musicians. In 1949, Rafferty emigrated to the United States, joining his sister. He soon married and raised a family of five: Kathleen, Teresa, Michael, Patrick, and Mary Bridget.

With encouragement from fellow musicians from home who also emigrated, Rafferty began to play music more frequently and in 1976, he joined a group of Irish musicians invited to perform at the Smithsonian Institution's Bicentennial Festival of American Folklife. Rafferty subsequently toured with the premier Irish traditional music and dance group Green Fields of America and has appeared at an extensive array of concerts and festivals all over America. As a tradition bearer from Ireland he was influential in helping Ireland's traditional music organization Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireann (CCE) establish itself in North America through the Martin Mulvihill Branch. Since then, a branch has been named after him, the Michael Rafferty Branch both in New Jersey.

An outstanding proponent of the East Galway style of flute playing, Rafferty devoted more time to teaching and playing music when he retired in 1989. He appeared on many recordings and has recorded three albums with his daughter Mary, an accomplished flute and accordion player: The Dangerous Reel, The Old Fireside Music, and The Road from Ballinakill. Rafferty released his solo CD Speed 78 in 2004. "No Irish traditional musician on either side of the Atlantic has created a more impressive body of recordings over the last nine years than flute, whistle, and uilleann pipes player Mike Rafferty," wrote the Irish Echo in 2005. In 2009 at the age of 82 Rafferty produced The New Broom with New Jersey fiddler Willie Kelly, whom he mentored.

Rafferty has devoted a lifetime to exploring, performing, and teaching traditional Irish music to students on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to teaching privately and at the Catskills Irish Arts Week -- the largest summer school devoted to traditional Irish music and dance in North America -- Rafferty has taught through the New Jersey State Council on the Folk Arts Apprenticeship Program. In 2003, he was named Irish Echo's Traditional Musician of the Year.

Interview by Josephine Reed for the NEA

NEA: I want to begin at the beginning. Where and when were you born?

Mike Rafferty: On September 27, 1926 I was born in the Village of Larraga, in the parish of Ballinakill, in East County Galway.

NEA: And how many kids in your family?

Rafferty: There were seven of us. I was the fourth, one of the boys. The three boys were older than me and the three girls were younger than me.

NEA: And what did your father do?

Rafferty: He was just a small farmer, but he was a great flute player in his time and he was the one, of course, that showed me the music.

NEA: So, you came from a musical family. There was music in your house.

Rafferty: Yeah, there was music in my house and my mother, she didn't play music, but she had a brother that was a great flute player. So, there was music on both sides of the family.

NEA: Now, your dad's nickname was "Barrel." Where did that come from?

Rafferty: He got a great tone out of the flute and they said he could fill a barrel with wind and that's how that came about. There were seven families of Raffertys and we weren't related. To differentiate for the postman -- the mailman, if you will -- they were all nicknamed. We were the "Barrels" and the other ones were the "Gads" and the "Slaps" and "Jennings" and they went by that name. And there's only one there now in the whole village. It's a remote area; it's farm country. That's what it is. Everybody had a little small farm. Maybe 20 or 30 acres of land was the most anybody had around that area.

Like everything else, everybody was self-sufficient at that time and they had to be. You know, you had your own milk and made your butter and bread and all that. There was no such thing as going to the store and buying stuff you couldn't get. You could buy the tea and sugar, that was about it, and maybe flour sometimes. But you had your own wheat and you went to the mill and you got it ground into flour and that was the way things were. Everybody was happy doing them things.

NEA: What did the countryside look like? When you opened the door of your farm, what would you see?

Rafferty: You would find plenty of fresh air and the green fields, the different colors when they have the crops planted, like oats is one color and wheat is another color, and a little field of potatoes is another color. And if you could fly over, it's beautiful, but if you're up on a hill and look at it, it's beautiful. I really treasure that today when I see a picture of it. "The Green Fields of America" is the name of a tune but in Ireland the fields stay very green because they get quite a bit of rain. Mother Nature takes care of it.

NEA: So, your dad would work all day in the fields, and then in the evening when you were doing chores would he play?

Rafferty: Yes. I started learning how to play when I was about seven and a half on the whistle and then he would show me every chance he got, every time that I might be around, at night and the wintertime was more appropriate -- there was less work to be done.

NEA: Are you the only one in the family who plays?

Rafferty: Yes, I was the only one. He tried with my three older brothers. They tried it, but I don't know how they fell away from it. They weren't successful with it. Somehow or other, their fingers wasn't doing anything for them and he used to bring that to their attention: "Your fingers aren't moving like I want them to." So, when I started out, he was bent on making me play because he knew that I could do it.

NEA: And was he a good teacher?

Rafferty: Oh, yeah. I used to watch his fingers. Nobody could read or write music in them days, around there that I know of, and he showed me his fingers and he'd play a little section at a time and we'd go back at it and he'd say, "Practice that section now" and so on. That's how it went, from section-to-section, and then you grew into it.

NEA: Now, your father lost his eyesight.

Rafferty: Yeah, at an early age. I was very young when he lost it. I wasn't playing when he lost his eyesight. I just barely remember when he did have some sight, and it was from cataracts and in them days, of course, there was no cure for it. Nobody knew what it was and my mother thought it was from blowing into the flute, that it'll make you go blind.

NEA: So, she didn't like it when you started playing.

Rafferty: She did not, and as I grew up, she gave away a flute that belonged to me. But I can't blame her for that. This was her thinking. She said, "Maybe we could get a fiddle, you could take up the fiddle." My father's first cousin over the road, over a couple of fields away, he was a nice fiddler, but I wasn't interested in the fiddle. I was starting on the whistle already. I was advancing onto the flute.

NEA: So, your father was blind when he was teaching you the flute, but he could just hear your fingers were not doing what they were supposed to be doing?

Rafferty: All I had to do was watch him. He was left handed and I was right handed and that made it that much easier. If it wasn't the right note, he knew it.

NEA: Did you also play at parties before you left Ireland and came to America?

Rafferty: Oh, yeah. I played with a band. We used to play for dancing. They had the dance halls over there at that time and of course, I had gone away from them for a number of years now, but there were local bands. There was a band in the parish where I was, Ballinakill Ceili Band, and there was the Aughrim Slopes Ceili Band. There were so many in the parish where I come from. I couldn't get my place. So, there was [a band] 11 miles down a road and they commandeered me. It's known as the Killimor Ceili Band. And once a week or it might be sometimes twice a week, we'd play as a ceili or something. There was money involved in it then.

NEA: What's a "ceili?"

Rafferty: A Ceili, it's a gathering of people and dancing and you're playing for them, the different sets and stuff like that.

NEA: Is there a particular Galway style of flute playing?

Rafferty: I suppose there was in them days, but right now, Galway and across the neighboring counties, there's more or less a standard style. I wouldn't be able to tell whether you were from Galway. But years ago, you would tell, especially a fiddle player, but I don't know about the flutes that much. And of course, like everything else, the transportation wasn't great. You walked. There were no cars. There were only one or two cars in the parish. Of course the priest at the parish, he had a car and maybe a teacher that was teaching in the schools. They were making the money, you know, so they could afford a car. There weren't that many cars around anyway in them days.

NEA: And Ballinakill, why do you think there were so many flute players there?

Rafferty: I don't know. It was just a nest of people that got together. That's the way it was over there. I guess one person learned it from the other. I don't know why, but they were there and they're all gone out of there. The older ones have passed away and the younger ones, some of them didn't take up the music.

NEA: And what about the Ballinakill Ceili Band?

Rafferty: They were known as the Ceili Band. They were traditional players. They made recording as well. They played for the ceili dancing. The parish priest would run a dance in aid of the hall or in aid of the church and of course they'd get so much money for them. The rest would go in aid of the church or a fundraiser sometimes and all clubs would be doing the same.

NEA: Do you remember your first flute?

Rafferty: Yeah, it belonged to my father. That was my first flute. Naturally, it would be handed down.

NEA: And it must have been quite an occasion when he gave it to you.

Rafferty: Well, it was sitting there. "Just play it," he said. He wanted me to play it. "You try it" and we shared the flute in other words, yeah.

NEA: Do you remember the first time you played outside of your home at a party, at a ceili?

Rafferty: I was maybe 16 or 17 but I couldn't tell you the exact age. There was a fiddler; he was a bit older than me. We used to be asked to play at house dances or parties, whatever you want to call them, and maybe that would be two or three times a year. There was another thing they used to have too and I played a lot of them -- Harvest Home. When they'd have all the harvesting done and the wheat and they'd be threshing the wheat and all of that and there would be a party in the house that night. And I worked for a guy that had that machine. We'd go from house-to-house. Then, of course, I was 18, 19 and 20. I was 23 when I came out here.

NEA: Why did you decide to leave Galway and come to the United States?

Rafferty: Well, here's the green far away. That's the kind of thing, for a better living. Of course, it was just after the Second World War and things weren't that good over there or any place in the world, as a matter of fact. So, I had a sister who came over here ahead of me and she got me out here.

NEA: When you came here, you went to New York?

Rafferty: The person that picked me up, he was a policeman in New York and he put up the papers for me. He was a friend of ours. I knew his brother in Ireland and his sisters and he agreed to put up the papers for me. I came to White Plains, New York.

NEA: But the difference from Galway must have been enormous.

Rafferty: It was enormous and it was just before Christmas and you're coming through the city and every place is lit up. It was very exciting. I was really greenhorn, to be honest with you. That's what they called them years ago. They were greenhorns. They knew nothing. You come from the country, you come into the city. It was a different lifestyle all together. So, I got used to that in a short time.

NEA: Well, you were lucky you had family.

Rafferty: I had my sister and I stayed with her and then I went to work as a gardener. That was my first job here and then I stayed with that for a while and then the Grand Union Company was hiring. They're not around anymore. They were a food store. I went to work for them. It was more money.

NEA: And were you playing at this time?

Rafferty: No, music was slack. I thought everything was gone. Music was slack at that time. There was nobody to play with. There was one fellow, he came over two months ahead of me, but he was living in the city and I was living in Purchase, New York. And then, of course, I moved to New Jersey and he was living in New York and transportation was rough at that time, until you got to know the trains. Then I got married in 1953 and then you're raising a family and you had to concentrate on work. I hadn't played for a long time.

NEA: Would you play at home occasionally?

Rafferty: No. Then I worked two jobs. I worked as a part-time bartender as well.

NEA: So, you were busy raising, how many, four or five?

Rafferty: We had five, five children.

NEA: That's a big family.

Rafferty: Five was plenty, let me tell you. Keep an eye on them and you know how it is, yeah, but they all turned out good.

NEA: Well, what brought you back to music?

Rafferty: There were two accordion players from home with me, they were only boys when I left and they come out ten years later and they were the ones that got on to me, "Why aren't you playing?" They encouraged me back into it again and then I got a flute and then I could get around a little bit here and there. They had sessions in New York, in the Bronx, and I had my tape recorder and I used to tape the tunes, tunes that I forgotten to be honest with you. Then I would come home and practice. And then Mick Moloney, he came along and he was the one that took me out of my box if you will, and he recorded me in the house. Then I got into it, and then I went on the tour with the Green Fields of America. That was three weeks.

NEA: Now, how old were you?

Rafferty: 1979 I went in the tour. But I was practicing for a year before that.

NEA: So, you were in your 50s when you picked up the flute again.

Rafferty: Well, I was playing a lot before that, but not good enough to go on the stage and play without a lot of practice. As we went on the road, I picked up a lot of stuff.

NEA: What was that like when you first went back and there you were, on a stage?

Rafferty: Yeah. Well, it came back to me. It was like learning all over again in one sense, but I had what it took to do it. I knew how to do it, you know, get the tune in your head and that's about it, and practice with the other ones. I didn't have too much of a problem with that. It was there except to do it and as you know, practice makes perfect.

NEA: And you retired from the Grand Union.

Rafferty: I retired from the Grand Union in 1989 and that's when I really paid attention to the music and then, of course, my daughter, she had taken on the music.

NEA: Your daughter Mary.

Rafferty: Yeah, and that was a big interest to me and that was a big thing for me. When she was a little one, wandering around, anything she seen me do, she wanted to do as well ? "Dad, I can do that." "By golly," I said, "There's no reason why you can't." And that's what it all started from. But then, at that time too, I was working two jobs, at night the bartending, and I wanted to send her to Martin Mulvihill. He was a great teacher in the New York area. He said to me, "Why are you sending her to me?" I said, "Because you're going to teach the notes and I can't and I don't have time, Martin and I'll appreciate it." But when Mary was at home, she had a tape recorder with her and he'd put the tune she'd be learning from him on the tape and I could learn it and show her and she went back with the tune off by heart. So actually, she had two teachers. I gave her a lot of attention. And of course, as she grew up then she was a little shying away from it. I said, "Don't hide your Irish culture. Never be ashamed of that because," I said, "You can be proud of that." So, I coaxed her into it. I was very happy with her.

NEA: You were clearly teaching Mary, but you also became a renowned teacher. One of the great teachers of Irish flute playing.

Rafferty: Yeah, when I retired. My wife Teresa got on to me. She says, "Why don't you start teaching." I had a bunch of little kids and some of them were beginners and I didn't care a whole lot for that. I said, "It would be better if they were advanced," but I did that for about a year and a half. And then Mary grew up at that time too and she was helping to teach. She used to teach the accordion and I was teaching the flute and whistle and Mary used to teach the whistle as well. I didn't travel around to teach except they got me to go to North Carolina and West Virginia to teach and other places I've gone for weekends and stuff. That was part of your job. You have to do workshops they call it.

NEA: Well, how was that for you? Did you like doing it?

Rafferty: That was nice. You meet nice people. You meet nice people along the road. Some of them were good. I was there a week in Milwaukee one year. I spent a week there teaching and that was great.

NEA: And are you surprised by who comes to you to learn how to play the flute?

Rafferty: No, not really, but they have to be advanced. I won't take on beginners. That's written down in the statement before they ever send in their application. They bring their tape recorders and I put the tune on for them. I show them like my father showed me and they get used to me after a little while and they pick up the tune rather than read it out of a book. It's faster this way. You can learn a tune much faster.

NEA: What was that like for you the first time you were in a recording studio?

Rafferty: It was kind of fun the first time, but then you'd make a mistake and you had to go back over it again and they didn't have the techniques of taking the bad part out and putting the good part in like they do today. The first time I did it, you had to play it all over again and hope you wouldn't make a mistake. It took three days to do the first one. Even the last one that we did with Willie Kelly, that took three days.

NEA: You made a CD with Mary.

Rafferty: Oh, I did. I made four CDs. The first one was The Dangerous Reel. I think the second one was Old Fireside Music, the third one was The Road from Ballinakill and the fourth one I made then was kind of my own, but Mary was with me on it. And then, Mary made one on her own and I played a few a tunes with her on it and then, of course, the last one I did [The New Broom] with Willie Kelly, Mary conducted it, and Dónal [Clancy] backed us up with the guitar; that's my son-in-law.

NEA: You play often older songs; songs that you heard growing up.

Rafferty: Yeah, I like to keep the old ones alive because some of the new tunes that are composed, I can't take a liking to them. But some of the older tunes, for the history of them alone and for the old folks that play them or even compose them. How they did or how they learned them is beyond me, but they left the groundwork for me to do them and any one of them that I think of, I can play. I love to play them. The novelty never wore off on them. The tunes, there was nice feelings in them.

NEA: You play tunes that you learned from your father or that your father would play and you play them with your daughter.

Rafferty: That's correct, because she was very interested in that. She said, "Did your dad play this...I want to learn that." So, I used to make up a little cassette for her and I would give her tunes to learn them and every time we do a concert she would talk about that.

NEA: Well, you talked on your CD, Speed 78.

Rafferty: Yeah, Speed 78. That was the one I did on my own, more or less, but Mary played with me too.

NEA: I appreciated having a little bit of the history and then the tune and that's unusual to do that. I mean typically when you pick up a CD of music what you're going to hear is music.

Rafferty: Well, the old Ballinakill Ceili Band -- Anna Rafferty and of course, the priest was the founder, Father Tom Larkin -- both of them I think were able to read music and that's where a lot of them really came from. And then, my father had old tunes as well. They had older tunes, you know, and some of them were a bit selfish with them in a way. My father wasn't that way. They wouldn't play it for everybody unless you were around and of course, like everything else, if you didn't know how to write it down and there was no tape recorders, and then they used to tape them to keep them, you had to learn them and you could forget it and that's what happened to me. I forgot some tunes in that respect.

NEA: The Smithsonian Folklife Festival in 1976 was a big deal, wasn't it?

Rafferty: That was a big thing for me. That was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. That made me spend more time, regardless, every minute I had, to play and sit down before I went on. That was a big thing, and then I learned a lot that week. That was the Irish week and the Bicentennial celebration. That was a big thing.

NEA: And when did you start coming to the Irish Arts Festival?

Rafferty: Well, I can't remember the year, but Don Mead, he was chairing it at first, like Paul Keating is doing now, and he used to ask me to come up, but we always had booked for Ireland when he would think about asking me and I didn't come up. And of course, Jack Coen, he was a friend of mine, he was coming here then too, but Don Mead wanted me to be here as well. He said, "You can teach" and all of that, but I turned him down each time. I said, "Well, the next time they ask, we won't be going to Ireland," I said to my wife. So, this is when it happened. I forget what year, but I'm coming up for five or six years now, maybe more.

NEA: Now, when you go back to Ireland, do you bring your flute? Do you play there?

Rafferty: Of course I do. I just go to the pubs and have a few tunes with friends and stuff like that. We find out where there's a session going and they have what they call the Singing Pubs over there, but there's very little singing. Now and then maybe you get somebody to sing a song. We play and drink a couple of pints of Guinness and so on. A couple of times, I was asked to play with a couple of people, you know, but it would be no money, just for the fun of it.

NEA: People call your flute player very lyrical. Do you think that's the case?

Rafferty: Well, it's the old East Galway style. That's what I call it. Nobody's playing in my style. A lot of people want to learn that style.

NEA: Can you explain what that style is?

Rafferty: It's more or less a slow style. What I would call it is playing the tune and playing it with feelings in it, like a good singer from a bad singer, with the nice tone of voice and clearing the notes. That's my only way of explaining that.

NEA: And when you listen to music, your daughter aside, who do you listen to?

Rafferty: Well, there's a lot of great ones out there. I love to listen to a good piper. Of course, the old folks are dead and gone. I like to listen to all the good ones, if you will. Brian Conway from New York, Seamus Connolly, he's living in Boston and a lot of them great fiddle players, yeah, The Kane Sisters is out from Ireland, they're here. There's three Concertina players. I think all three of them are from Clare. They're very, very good.

NEA: And finally, how did you learn that you received a National Heritage Fellowship Award?

Rafferty: Barry Bergey called me on the phone. I was sitting on the couch and my wife answered the phone and she come down the stairs. We have a basement and I was sitting down there. During the day for an hour or two, sometimes I go in there and I practice, play a few tunes for myself. Or if I hear a new tune that I don't know and I like it, I will learn how to play it just to carry on. She comes down the stairs and I said to her, "Oh, we won the lottery finally." I thought that's what happened. "No," she says. I was nominated for years and they gave it to Joe Derrane and well, I had forgotten completely about it, but I was nominated again. I didn't have a clue until he called me up. He says, "I'm not joking." Well, I hope you're not. He explained the whole thing to me. So, it was a surprise let me tell you. And all the congrats from everyplace. They called me from Ireland when they got a hold of it, musicians from over there, a couple of people that has radio shows over there that I know through the music, calling me up congratulating me and so on. There's a couple of people from England as well that I know, flute players and accordion players and so on. And of course, all over the United States they call me up. Well, I've traveled around. Everybody knows me from the teaching and they remember me from whatever I did.

NEA: It's an honor that's so well deserved and everybody was just so thrilled that your name was there.

Rafferty: Yeah, everybody was. Everybody said that. But like I said, how could I have earned something like that? I love what I do. That's one of my loves. I love Irish music and I love to play and that was something that I loved really and I share it with others and that's about it.

NEA: It's so interesting isn't it that Irish music, how many generations old is it and here we are in the 21st century and you're still teaching it, people are still playing it. There's a whole younger generation out there eager to pick it up.

Rafferty: Well, there was another thing that amazed me and I was very happy with when they took up the Irish music here in America. There's a lot of Irish people and they don't know nothing about Irish traditional music. That's as true as I'm sitting here and yet people with no Irish blood in them at all and they love it and play it very well indeed.

NEA: What makes Irish music "Irish music?" What is it about it that is distinct?

Rafferty: Well, for one thing, the songs, they have sad feelings in them. Irish traditional music has a sad part, but it has very lively parts as well, and I guess that's the only way I can word it. Like for dancing, they hop around and everybody seems to come to life. It's nice to watch them dance, to be honest with you, and they enjoy that and of course, they have to have music. The dancers, they understand the music as well and the timing of it. And then the songs, some of the lovely songs that are sang. There's lovely feelings involved. A lot of them are love songs, but they're very nice and they're not like that, what do you call it, that rap music. I don't care for that, but to each his own. A lot of people fell in love with Irish music.