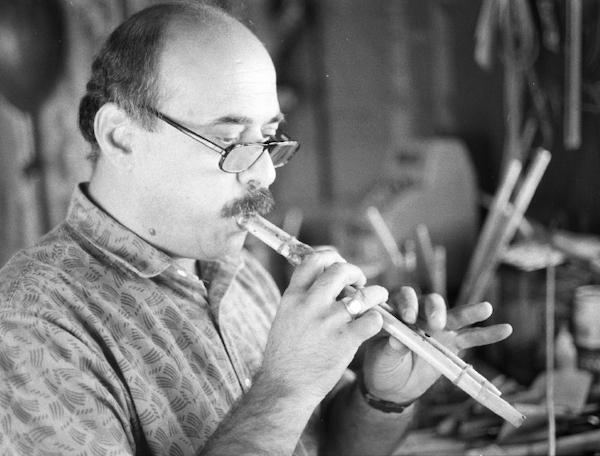

Nadim Dlaikan

Photo courtesy of the artist

Bio

Nadim Dlaikan was born in Alai, Lebanon in 1941, and as a child began playing the nye, a reed flute. Although his family discouraged him from playing this instrument because it was associated with lowly shepherds, he persisted and even found ways to make his own flutes out of locally grown reeds. Dlaikan began studying after school with Naim Bitar, the country's premiere flutist at the Lebanese Conservatory. Upon graduation Dlaikan moved to Beirut, and traveled frequently throughout the Middle East as part of Lebanon's best-known folk troupe. In 1969, a staff member at the U.S. Embassy heard him playing at a Fourth of July party and encouraged him to perform in the United States. Dlaikan first came to the U.S. as a back-up musican for Lebanese pop singer Samira Tawfik. Eventually he settled in Detroit, home to the largest and most diverse Arab community in the country. Sally Howell of the University of Michigan says musical groups in the Detroit/Dearborn area are an eclectic bunch. "An ensemble of such musicians may contain a self-taught Palestinian American, a recently arrived Lebanese who was trained by an uncle in a very traditional setting, an Iraqi Christian who picked up his love of music in an Iraqi garage band, and a Turk who is still struggling to learn enough Arabic to keep up with what is being said." Within this cultural mix, Dlaikan is recognized as a teacher of tradition and the artistic glue that holds both musical groups and the community together. In addition, he is recognized nationwide as a premiere maker of flutes and a master of his own unique musical traditions.

Interview with Mary K. Lee

NEA: Congratulations on your award. What was your reaction to hearing the news?

MR. DLAIKAN: I was so happy about it. I think I deserve it.

NEA: Can you tell me who were the most significant influences in your career?

MR. DLAIKAN: My family. My sisters and my brothers. They encouraged me to play this music. My oldest sister used to drive me to school to study the music twice a week when I was young.

NEA: Are they musicians also?

MR. DLAIKAN: My brother played the flute, the same instrument I play, but he no longer plays.

NEA: Can you tell me about learning how to play the flute and what was that like for you?

MR. DLAIKAN: The Arabic flute is the instrument the shepherds played back in the Middle East. I think every village or every town in the Middle East has one or two people that play it, especially at weddings. It's a very sensitive instrument made of bamboo and reed, and is a very difficult instrument to learn.

NEA: What makes it so difficult to learn?

MR. DLAIKAN: Because it's got open holes, not keys like a regular flute. You have to make the sound with your finger, by your feeling when you blow. It took me about six or seven years in school to learn how to play. It's very hard to learn and to play. You have to be smart and love the instument to play it well.

NEA: Can you tell me about your coming to the United States?

MR. DLAIKAN: I came to America back in the early seventies. When I was working as a professional musician in Lebanon, the band I was with was hired to play at the American Embassy to celebrate their Fourth of July. We played there and I met an American guy from Pennsylvania who told me he'd never seen an instrument like my flute in America. He encouraged me to come to America to play. I came to United States in 1971 with a group to tour and I decided to stay. I've been here since 1971.

NEA: What was the response of the people here to the music?

MR. DLAIKAN: When I first came I lived in New York City and of course there were many Greek, Arabic, Turkish and Armenian people there. That's why I went there. I was so happy to see people who wanted to listen to my music. I think I was the first to play this instrument here. They were so happy to see somebody play this instrument.

NEA: Are there more players now?

MR. DLAIKAN: Yes, there are more now because after the seventies, because of the situation in the Middle East, a lot of people keep coming over here. The community is getting bigger and bigger. I perform now with players of all different nationalities - Armenian, Arabs, Turks - because their music is very similar.

NEA: How do you get the materials to make the flute?

MR. DLAIKAN: I live in Michigan you know, and the weather is very cold, especially in the wintertime. The bamboo and the reed aren't native to Michigan. I went with my wife to visit my sister-in-law in California and I saw bamboo growing all over, so I brought bulbs back with me and planted them in my backyard. It keeps coming up every year. In the wintertime I cut it down and in the summer it keeps coming up. I'm the only one who makes this instrument in the U.S. People call from all over the country to order flutes, all types of flutes.

NEA: Are you teaching others to play and make the flute?

MR. DLAIKAN: I'm teaching a couple of people to play but not how to make the flute. One who teaches in a university here in Michigan is interested in making the flute. But she's far away and that makes it harder to explain. And it's hard for her to find the bamboo.

NEA: How is it for the students that you are teaching to play? Is it pretty difficult?

MR. DLAIKAN: They're musicians, studying the clarinet and other instruments and they read music. But in the beginning it's very hard to make a sound, to change registers and so on.

NEA: Tell me about your repertoire. Is it just traditional songs that have been passed along or do you write your own music?

MR. DLAIKAN: I composed many songs and music before. I've got a couple of songs for guys who are singers back in the Middle East - when they come over to tour I give them some melodies. And I compose music for American bands and musicians. Most of them are traditional in style, some are a mix of western and eastern music.

NEA: What are most of these songs about?

MR. DLAIKAN: Most of them are folk songs, traditional songs, very, very old songs especially for the dance they call the debka in Arabic, a circle dance. That's the most popular thing we do in a concert or a party. That's what everyone wants to do there.

NEA: Why is that so popular?

Dlaikan:Each community has its own traditions, but everybody does the debka.

NEA: Are you open to more contemporary forms of music or do you prefer the traditional?

MR. DLAIKAN: Traditional music, for the most part, because it still lives on. The new songs coming out are the commercial songs, they don't live more than two, three weeks. But people still remember the old songs and they love them. The composer of the traditional music spent so much time to put the music together, but now a musician composes fifteen songs in one hour. Everything tends to be commercial now. You make a song, then throw in the market, and see how many CD's you're going to sell.

You know, they can play all kinds of instruments on the synthesizer, on the keyboard. But people like to see the instrument, you know what I mean? When you make a sound on the keyboard like a guitar or a trumpet or a flute, the people hear the flute but they like to see the flute. I like to go to the symphony orchestra to watch the instruments of fifty or sixty musicians - I like to watch what they're doing. That's what's interesting. With the Arabic band here, we've got seven or eight very unique instruments. People love to come and take pictures of my instrument and have me explain to them how it makes the sound. That's the most important thing, you know.

NEA: Does that make it more difficult for traditional music and musicians to continue on?

Nadim MR. DLAIKAN: It will take awhile to die out, but it's going to be gone in 25 years, especially with the young generations mixing up western and eastern music. I'm telling you, the music being composed right now has no flavor in it. The composer wants to make money and doesn't worry about whether the song is going to live on or not. But when we perform, we play music that's fifty or a hundred years old. People are still asking for it. It's very rich music and you have to be a real professional to do it.

NEA: What are your emotions when you play? What kind of emotions are you trying to get across to the audience?

MR. DLAIKAN: How can I explain it to you? I love this instrument. I feel like it's a part of my body. I feel very good. With any instrument, not just the flute, if you didn't love it you're not going to make a very good sound. You have to hug it tight to make a good sound.

NEA: And your audiences, what are you hoping that they're experiencing?

MR. DLAIKAN: Americans love it, because they haven't seen an instrument like this before. They come to the stage to ask me how it's made and how I make the sounds. When I play the melody on the stage I have keep changing flutes, keep changing to different sizes.

NEA: What does the size do, change the sound?

MR. DLAIKAN: Each flute - unlike an American flute - each flute has it's own key. G and B and A. When the singer is going to sing in the G, I have to grab the G flute. When somebody wants to sing in D, I have to grab the D flute. That's why I have to carry so many flutes with me.

NEA: Now how many would you normally carry for each performance?

MR. DLAIKAN: The suitcase I carry them in can hold ten or eleven flutes.

NEA: Did you teach yourself how to make the flute when you were a child?

Dlaikan:As I said, my brother used to play the flute. One time I grabbed his flute and played it. He got mad and hid it, and told me not to touch it. So I went to the field and cut the bamboo and made one similar to his. When I studied the flute in school, my teacher showed me how to make one.

NEA: And what is the Middle Eastern community like there around Detroit? Is it a pretty active community there?

MR. DLAIKAN: Oh yeah, of course. That's what I make my living now, I work three nights during the week and on weekends. Weddings, festivals, conventions and parties. It's a very nice crowd we see all the time. They are very proud of our traditional music.

NEA: Just one more question. What are you looking forward to when you come to D.C. for the awards ceremony and the concert?

MR. DLAIKAN: I'd like to meet the people who've given me this award. And I'd like to meet the other people who are being honored, find out more about them. And I've never been to Washington, DC. My wife and children will be coming with me.