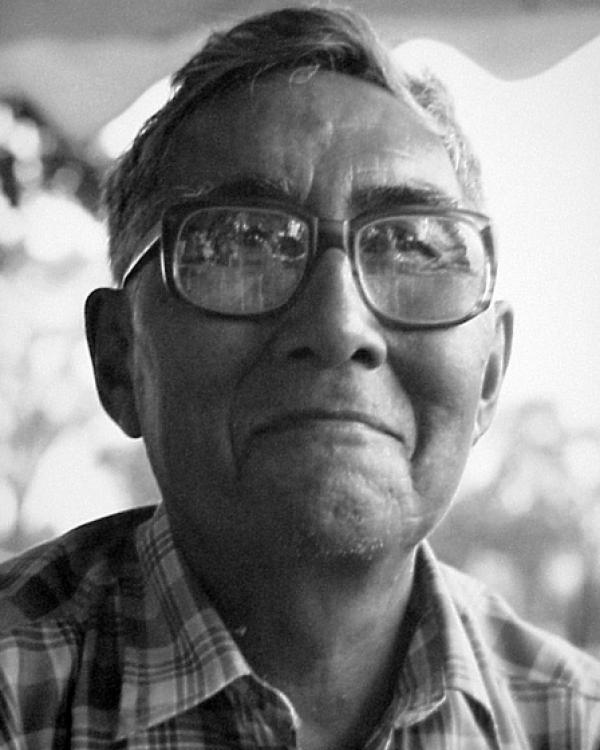

Paul Tiulana

Photo by Kathy James, National Council for the Traditional Arts

Bio

Paul Tiulana was born in 1921 on King Island in the Bering Strait, just off the Alaskan Seward Peninsula. He was an Inupiat Native, and was taught at an early age how to survive in nature, how to hunt, and where to go on the ice floes to look for seals. In addition, he learned how to mark moving ice, shore ice, and mainland ice to help understand drifting patterns and other necessities of living on a remote Alaskan island.

Tiulana started going to school on King Island when he was nine years of age. That same year his father died, and his uncle, John Olarrana, became his mentor. Under his tutelage, Tiulana grew up to become a leader in the preservation of Inupiat traditions. He was an accomplished ivory carver, mask maker, singer, and drummer. He made the perpetuation of the culture and heritage of the King Islanders a major concern, and he devoted much of his life to this work.

The King Island Eskimos were forced to leave their island in the 1950s and were resettled in Nome, Anchorage, and other locations in Alaska. Tiulana taught carving classes and workshops for the native organizations that serve Anchorage, and he was a member of the King Island dancers for more than 40 years, and served as their leader starting in 1956. He toured extensively with this group throughout Alaska and in the lower United States. He spearheaded a project to build a traditional skin boat, or umiak, in 1982, and he played a key role in the revival of the ceremonial Wolf Dance, which was finally performed in 1982 for the first time in more than 50 years.

In 1983, Tiulana was named Citizen of the Year by the statewide Alaska Federation of Natives for his work in promoting cultural heritage. Rarely had a civic award of this nature been presented to a practicing artist. He was an exemplary craftsman, a vigorous and subtle dancer, and an expressive singer. He knew and could teach the survival crafts that were once so essential to the quality of human life in the Arctic, skills still vital to the maintenance and dignity among native populations. On completing his skin boat, a labor of many years, he wrote, "I have been taking a walk in the past." But throughout his life, he was firmly situated in the present, sustaining for his contemporaries and descendants the traditional values and complex aesthetics of the Inupiat Eskimo people.