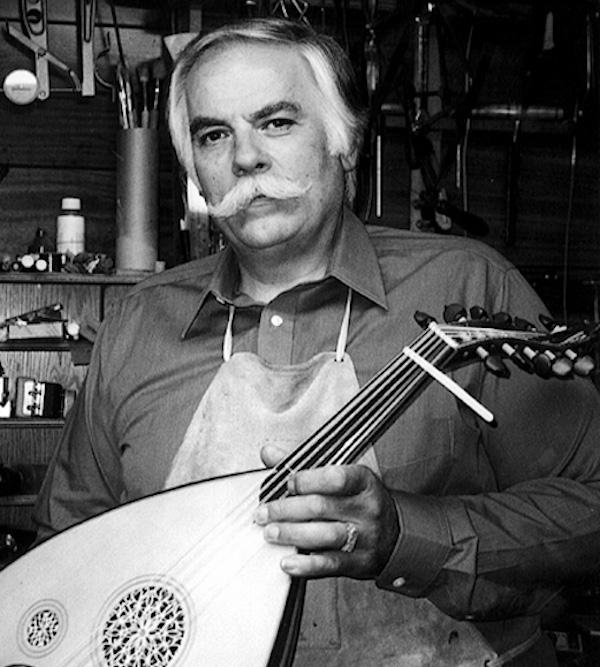

Peter Kyvelos

Photo courtesy National Endowment for the Arts

Bio

When 1989 National Heritage Fellow Richard Hagopian performed at the celebratory concert, he took the stage with an oud made by Peter Kyvelos. Hagopian refers to him as "the Stradivarius of oud making." Kyvelos has been making and repairing stringed instruments for over 30 years, and his shop in Belmont, Massachusetts, is considered to be the epicenter of instrument-making by Greek, Armenian and Middle Eastern musicians around the United States. He has built over 175 ouds, a member of the lute family, over the course of his career. His interest in instrument-making was sparked by his fascination with the music. As a youngster, he tried to play the Greek music performed by his father, an avocational woodworker. During his college years, he embarked on a serious study of the structure of the instruments. He began making and repairing them, even though he was still performing in clubs in California to earn his way through school. When he returned home to Massachusetts, he set up his shop called Unique Strings, not far from Watertown, known as "Little Armenia." His customers and admirers have spread both geometrically in number and geographically in breadth ever since. Still, for him, it is the joy of making the instrument and the satisfaction in seeing and hearing it played that inspires his work: "But the most exciting thing, of course, is when you've created an instrument and strung it up and it goes into the hands of a professional, and then you see that professional sitting up on a stage playing your instrument. There's a certain amount of pride that you get; nobody has to say anything - I don't even want people asking whether I made it - that's not it. What matters is between me, the instrument, and the person playing."

Interview with Mark Puryear

NEA: What was your reaction when you received the news of the award?

MR. KYVELOS: It came as a great surprise. It's a great honor and privilege. I'm very thankful. I never realized there were individuals out there who really cared. After thirty years of business it seems everybody's only interested in the bottom line, in how much the instruments cost. I get a lot of people telling me how beautiful they are and how they play so well and they've seen instruments I've made for other people and they want to order one. But the minute we start talking about price, things fizzle out. It's an ethnic instrument and most of the people that play it are from ethnic backgrounds. They want to get an instrument they can play or learn on. And I can empathize with them, obviously, because they are costly. But it's not really that much, frankly. I invest so many hours in making one that I usually end up making two or three dollars an hour profit for my time. So it's truly a labor of love.

Now all of a sudden here comes an organization that's actually applauding my ability and the time that I put in. That means so much to me. That can't be bought. You can't put a value on something like that. It's made up for all of those hard times in the past.

NEA: Many people who work with their hands and do things by hand in this country seem to be having the same problem.

MR. KYVELOS: In order to make a living, about 70% of my business has been repairs and restorations. Because there are people with good instruments that need repairing, I can charge a reasonable amount of money so I can make a living at what I do.

I've chosen to build an instrument I love, so I'm not complaining. But the demand for them after all these years is diminishing because there are fewer and fewer people who play the instrument. My competition comes from these really inferior instruments made in foreign countries that are literally just slapped together. These are the ones I do repairs on all the time. If you can buy a four or five hundred dollar instrument from overseas, why would you want to spend $4,000 to buy one of my ouds? Actually, most of the ouds I've made sold for well under $1,000. I was making about 65 cents an hour. Again, if it weren't for the repairs and occasional sale of other instruments that I've restored and sold, I could not have maintained myself and taken care of my family. Even now it's still a struggle. I'm 57 years old and I'm looking at five or six more years of working out of my store here. Then I'll do it part-time at my house. You know, the money's not going to be there, even with Social Security and a few dollars that I've invested. I'll just be eeking out an existence until the day I no longer walk this earth.

NEA: Why do you think that your artistry is valuable to your community?

MR. KYVELOS: Unfortunately, the type of instrument I build is not as important anymore because so many of the individual players that I built for in the past are now aged or deceased.

The second and third generations have married other cultures, which is fine, but when you do that something gets lost along the way. The children are from mixed backgrounds, one parent is Greek and the other Armenian or Irish or whatever and so the love and desire to play the music diminishes as time goes by with each generation. The instrument just isn't as popular as it was when I started building them over 30 years ago. When you had cultures coming at the turn of the - the huge masses of Armenians and Greeks and other nationalities, century, for instance, - their only tie to their homeland was the music and the church. There were a lot of clubs, a lot of gatherings, a lot of people playing the instruments, a lot of music floating around. They've passed away and their children and their children's children have sort of gotten out of their ethnic ties. The demand isn't there.

NEA: Who or what were the most important influences on you?

MR. KYVELOS: All the way back would be my father. We lived in an apartment house and he was very good with his hands and we were always doing things together. Painting and repairing things, wall papering. Through all of this I learned how to use tools and developed a good eye for things, for line and shape and so on. My mother was very talented in her own right. She was quite artistic though not trained as an artist. She was very good with her hands. She used to make a lot of things at a time when it was necessary to do those things.

As time wore on, a lot of it was intuitive on my part. I looked at things and figured out ways or possible ways of achieving that same thing. When I was little we used to get National Geographic. I was fascinated with the treasures that were taken from Tutenkamen's tomb. One of them was a long boat that had had slaves on it, oars and so on. There was something so beautiful about it. I was about 8 or 9 years old at the time. I went across the street to the old wood lot and found a chunk of wood long enough. I thought about it and started whittling away and about two months later, sitting on the back stairs, I finished it. I was able to achieve somewhat of a success. I mean, I was a kid and it was nothing great. That's the kind of thing I did when other kids were out playing baseball and doing the things that most kids did. I was usually sitting back somewhere alone carving and painting. I found some clay by the river nearby and took it home and learned that I could make things out of it. I could stick it in the oven at a very low temperature and it would dry pretty hard but not hard enough to really last, of course. But I could paint on it in tempura paint. Little by little, as I went through high school and left for college, art seemed to be a big part of my life. And music. I always loved music, especially ethnic music.

NEA: You have a strong creative streak.

MR. KYVELOS: It really seems that I look through different eyes. I would see a certain tool or piece of wood or whatever and I would look at it and say, "Boy, this would be great if I did this and if I modified it this way I could get this and it could do that for me, maybe make an improvement on what I'm able to do now." And so on.

As time went on there were certain people who recognized that I was really into the arts. They stepped forward and motivated me.

I took two years in wood technology at school in California and built my first oud in the first of those classes. In the second class I built a kanun, also a very difficult instrument to build, a sort of Turkish zither. The instructor was amazed at what I was able to accomplish there.

I went on to take two years of plastics technology courses. I did that simply because I wanted to learn more about what at that time was a really new material. And I learned how to do lay-ups with fiberglass and I was able to make cases. I got to brainstorming. "Gee I could make the back of an oud out of fiberglass, and a bazooki, too." So I made two instruments which I actualy sold for very little money to a Greek guy in Modesto. And they sounded great! But it just went against my grain, not working in wood. Wood's more beautiful and live. Working with this plastic material didn't turn me on. It was great for cases, not for instruments.

NEA: What are the biggest challenges in practicing or sustaining your work?

MR. KYVELOS: Trying to make people aware of the instruments I create. Not just the oud. I make two or three other instruments from the Middle East which have lost their popularity as well, for the same reasons. And getting out there and talking with people. I go to many of the few dances that are still around. When I was a boy growing up, we used to have to flip coins to decide which dance to go to because there were so many. But it's rare now to find even a club that feature the music. If it's a dance, it's maybe once or twice a year, instead of three or four times a month. It's difficult for me to reach out.

It's a difficult instrument to master, as well. It's very challenging. But because you have people who have been playing the violin and the guitar, probably the most popular instruments in the world, there's a dire need for people who build and restore these instruments. Those people are also used to paying reasonable prices for having their instruments restored. When they come in with a $50,000 violin and you charge them two to three thousand dollars to restore it, they think nothing of it. Everything is relative, obviously. But when someone comes in with an instrument that they've picked up from overseas for $200 and you have to charge them $250 to put 12 ebony pegs in and fit them and so on, they can't understand that. That's another problem.

Most classical guitar builders are getting five to six thousand dollars and up for their instruments, which usually take 50 hours to make. And here I am finally getting to the $4,000 mark. I haven't really sold any at $4,000, but that's been my price since two years ago. I've gotten no new orders since then, which is sad.

And I sit on all the wood I purchase for at least ten to twelve years. I have wood that I've had for 40 years. I have wood that I've bought from other makers that was old when I got it, so it's sixty, seventy years old. That plays into all of it as well. Whereas in the old country, they'd find an old crate somewhere that looks like it has some decent wood in it and make an instrument out of it.

NEA: What advice would you give to students or young people starting out working in your art form.

MR. KYVELOS: Choose an instrument to your liking, that you're really happy with. If you really want to make a living, consider that you're going to be putting in many hours and months and years not making a lot of money. But money isn't everything.

I've had about five people over the years come into my shop and some have stayed tow or three years. And I have a person now who's been here fourteen, fifteen years. He's renting space from me and does his own thing. He's very talented and he makes beautiful instruments. I taught him to build ouds and he's gone beyond that using pretty much the same technology but putting a lot of his own technology into it too.

NEA: What are you most looking forward to when you come to DC?

MR. KYVELOS: I'm looking forward to meeting the other artists. I'm sure we have a lot of similar stories to tell even though we work in different art forms. I've known many different artists, so I'm looking forward to meeting these individuals. And I look forward to meeting the folks like yourself who've made this possible.