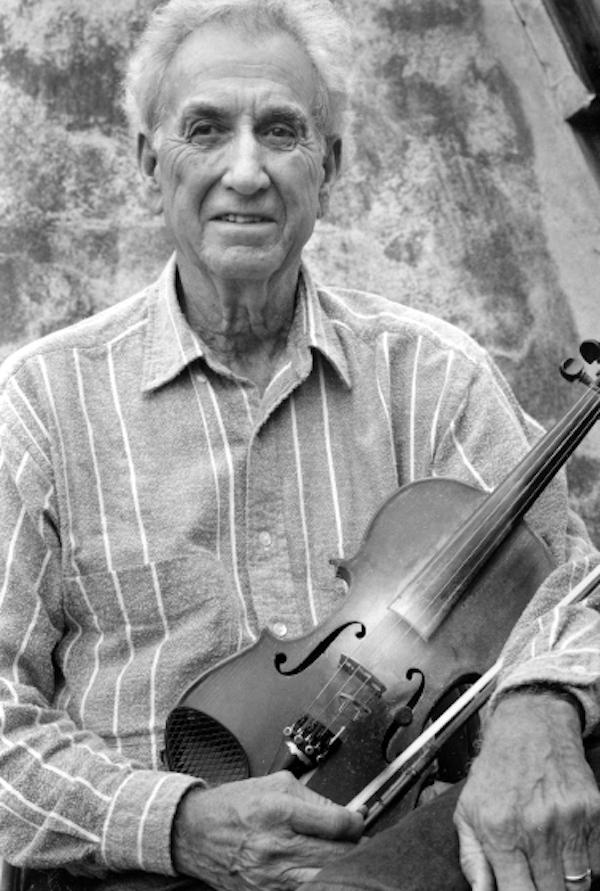

Ralph Blizard

Photo by Gerry Milnes

Bio

The area near the border of northeastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia has historically produced many fine string band musicians, earning it a reputation as the "birthplace of country music." Ralph Blizard was born in this musically fertile region in 1918. By the time he was 14, he was playing fiddle with his group, The Southern Ramblers, on an early morning radio show on WOPI, known as the "Voice of Appalachia." For the next 23 years, except for an interlude during World War II for military service, Blizard played on radio shows, at schoolhouse concerts and on variety shows. He then gave up music to raise a family and to pursue a career with Eastman Kodak. After retiring in 1980, he took up the fiddle again and began performing around the country for diverse audiences including Tlingit Indians at the Alaska Folk Festival, elderly nuns and retirees at a New York rest home, classical music aficionados at a concert with the Kingsport Symphony Orchestra, and a national audience of millions on Good Morning America. In addition, he has spent time teaching younger people his unique East Tennessee-style of long-bow fiddling, often associated with the legendary Arthur Smith.

Interview with Mary K. Lee

NEA: I want to congratulate you on your award. Could you tell me about your reaction when you heard the news?

MR. BLIZARD: I was really surprised and it didn't really sink in right away. I was really amazed.

NEA: Could you tell me how you learned how to play the fiddle? How did you get into music when you were younger?

MR. BLIZARD: Most of my friends and the kids in my neighborhood at that time were interested in music. Probably a higher percentage of young people played music then than today, I think. I started at a very early age - a cousin says I was playing fiddle when I was seven years old.

My mother and father always liked music. My dad was a fiddler and he taught shape-note singing. And three well-known fiddlers - Charlie Bowman, Dudley Vance, and John Dykes - lived near Kingsport, where I was raised. John Dykes lived within four or five miles. Charlie Bowman lived within, say, seven and Dudley Vance was about fourteen, fifteen miles.

I also got into playing guitar and the mandolin. Of course, the noting of the mandolin is the same as on the fiddle so it wasn't much of a step to play fiddle. I had a band by the time I was fourteen years old.

NEA: By the time you graduated from high school you were a professional musician. What was that like to be a professional musician at such a young age?

MR. BLIZARD: We started out like most others did, I guess. WOPI was the first radio station in this region - they came on the air in about 1929 - and we played on WOPI in Bristol. WOPI had another a studio in Kingsport at the old Homestead Hotel and we played music there early in the morning before school. We'd go by there and play the early morning program. Most of those shows were on the weekend, though, I think. I don't remember exactly.

The next station to came on the air was WJHL in Johnson City, which is about twenty-two, twenty three miles from Kingsport. But their studio was in Kingsport down on Market Street on the second floor of the Kingsport Times building where my dad worked at the newspaper. My band and another band originated a Saturday program called the Barrel of Fun show. I think the third announcer we played under got the idea of naming the program the "Barrel of Fun" when my band started playing Roll Out the Barrel.

NEA: You perform the long-bow style. Tell me why you prefer that style, why that works for you?

MR. BLIZARD: I wasn't the only long-bow fiddler back at that time, there were a few. But you have to look back starting from the time the first settlers came into America. Fiddlers from then on down had various styles but most of them had their own particular style of fiddling. The fiddler usually played by himself for dances and other entertaining and had to develop a style incorporating the rhythm into the fiddle playing.

The style sort of loosened up when the banjo came on the scene. So they began to develop different styles where you didn't have to furnish the rhythm. Some of them had a little bit of long-bow in them and some, like myself, had a lot of it. Long-bow refers to playing more notes with one direction of the bow, forward or backward. But you're not limited to that, you can still include the one note bowing backward and forward. I still use those techniques, but the dominating factor is that I play long-bow, which lets you get into more complicated phrasing.

NEA: I understand that you stopped playing music for a long time and worked for Eastman Kodak while you raised your family. What was it like being away from music for so long and then coming back to it?

MR. BLIZARD: I was away from it for over twenty-five years and of course I didn't keep up with the music scene. I retired in 1980 from Tennessee Eastman in Kingsport and when I retired I started learning to play the fiddle again. I had to devote quite a lot of time each day to it but I developed a method for learning pretty fast. I bought a cassette player and I ordered tapes from Joe Busserton. He was up in Maryland and he had just about everything that's ever been recorded. I got a lot of tunes that I use to play and got used to playing them again. I really devoted myself to those tapes, you know. I had headphones on and played along with the tape. That's how I got back to where I had been.

In May of 1982 I met the Green Grass Cloggers - Phil Jamison, Gordy Hinners and Andrea Dever - at Bays Mountain Park in Kingsport. They were playing at a festival there along with John McCutcheon, some of the Carter Family, and a lot of the other groups that were playing music at that time. I took my fiddle down to the festival and went up and told them I wanted to do some jam sessions with them. I'd been practicing and I'd gotten to where I could play fairly well. Well, they did a jam session with me and they were enthusiastic about it. Of course, I was really enthusiastic about it. And it amazed me that they knew the music I did. After playing with them, Gordy and Phil talked me into going into a fiddle contest and that's the way I got recognized again. I formed the New Southern Ramblers with them and we started playing professionally.

NEA: What efforts have you made to pass along your skills to others, especially young people? Can you tell me about any teaching that you've done or activism in schools?

MR. BLIZARD: At just about all the festivals we play we also do workshops. The workshops consist of the band members teaching what they do. Greta Henry taught banjo and Phil Jamison teaches guitar. They were professional clog dancers as well, so they taught the clog dancing. Phil Jamison is a professional square dance caller and so he teaches the square dance scene. I teach the fiddle, of course.

I teach my style of fiddling. Not that they would necessarily play the style but they would incorporate it into their own playing.

NEA: And you also make efforts get traditional music taught in school? Why do you think that's important?

MR. BLIZARD: I was appointed to the Tennessee Arts Commission in 1987 and my main goal was to get the music into the schools in Tennessee. But I was not successful in doing it, even after five years.

About a year and a half ago, we started the Traditional Appalachian Musical Heritage Association to teach and promote the heritage of the music, from the time when the first settlers came into the America to now. That includes all of the Irish, the Scottish, the British, the English, the folk scene and all that. I figure the Traditional Appalachian Musical Heritage Association has a national appeal and will be - if we can keep it alive - a national organization. And an international one because the New Southern Ramblers have done concerts, dances and workshops in Ireland, Scotland and England. I think of the Traditional Appalachian Musical Heritage Association as a common denominator and we'll get individuals and a lot of satellite organizations to join this and promote it.

The goal is the promotion and appreciation of our heritage. We hope to have a school to teach just about everything. I'm hoping that people interested in the folk scene, the traditional music scene, will work with us and share their ideas about how to make this work. We'll have a museum as well.

There's a world of songs and tunes out there that are disappearing.We're forgetting them. A lot of the musicians and fiddlers and musicians and singers have passed away without any record of them being preserved. Just like the music in my grandfather's time and my great-grandfather's and my great-great grandfather's time - a lot of that is gone and cannot be recovered. That's one of the things we need - more people studying this heritage, the folk heritage. I know there are quite a few people like yourself devoting themselves to that and I applaud that.

My goal is to try to get people to appreciate their heritage. And that's what's been taking place the last twenty-five, thirty years. And it is something that people in the traditional music field need to work on, to encourage people to be proud of their heritage,

NEA: Could you tell me what you're looking forward to about coming to Washington for the awards and the concert?

MR. BLIZARD: It's a great honor. I'm looking forward to meeting all of the other awardees and meeting the people who've supported the other people that are getting this honor. And I'm looking forward to seeing quite a few people that I've known before. It's going to be a great occasion.