Music Credits:

Excerpt of “St Louis Blues” composed by W. C. Handy and performed live by Dick Hyman.

Excerpt of “Royal Garden Blues” by Clarence Williams and Spencer and performed by Bix Beiderbecke, from the album Bix Beiderbecke: Vol. II At the Jazz Band Ball.

Excerpt of “The Moog and Me” composed and performed by Dick Hyman, from the album Moon Gas.

Excerpt of “The Lonesome Road” music by Nathaniel Shilkret and lyrics by Gene Austin, performed by Lee Wiley, from the cd Back Home Again.

“Beat the Clock Theme”, “Theme from the Purple Rose of Cairo” both composed by Dick Hyman; “Blue Monk” composed by Thelonious Monk, performed by Dick Hyman; all from the cd, Dick Hyman: House of Pianos.

<music up>

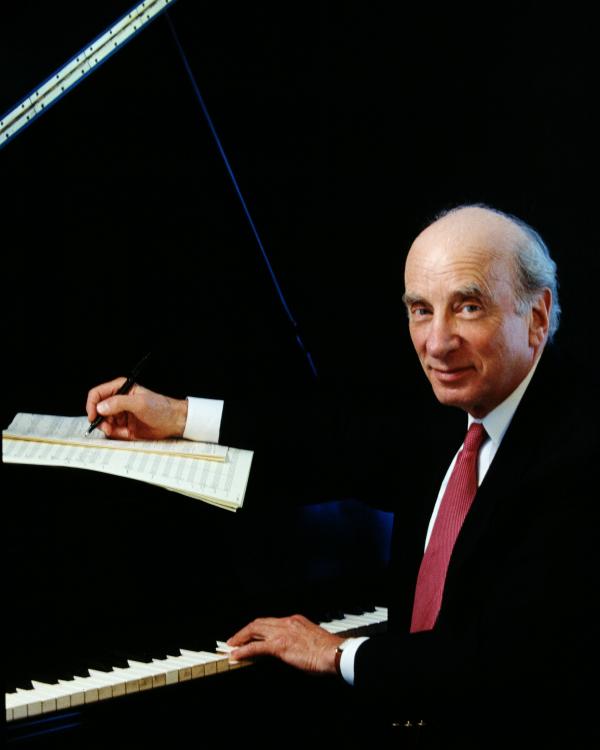

Josephine Reed: You’re listening to pianist and 2017 NEA Jazz Master, Dick Hyman.

And this is Art Works, the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

Pianist Dick Hyman combines virtuosity with extraordinary versatility. A masterful improviser on the keyboard, his heart is absolutely in jazz; yet, he’s also a composer of chamber music, a prolific award-winning studio musician, an orchestrator and arranger who’s worked with a who’s who of jazz singers, and he’s composed the soundtracks for more than a dozen Woody Allen films. He was music director at NBC for five years. Dick Hyman has worked as a solo artist. He’s played with small bands, and he’s played with full-sized orchestras. Hyman was one of the first musicians to record on a Moog synthesizer and he created and ran the Jazz in July series at the 92nd Street Y in New York City. In other words, he’s a musical shape-shifter—the word Zelig comes to mind—which actually is appropriate since Dick Hyman composed the soundtrack to that movie. Dick Hyman is now 90 years old and has put aside many of the hats he has worn in order to focus on the thing he loves most—playing solo jazz piano. Piano and jazz have been the two constants in Dick Hyman’s professional life. His uncle might have been a concert pianist and Hyman’s first teacher, but it was Dick’s older brother who led the way to the music that would define him….

Dick Hyman: My uncle, Anton Rovinsky, was a—a pianist, a concert pianist. He played recitals in various places, settled into teaching, and I was one of his pupils at one point.

So he was the main musical member of the family. The other most influential, maybe more influential, was my big brother, Arthur. My big brother was the one who collected all of these 78-RPM records, which you can see up there, which were tremendously influential on me. I’d memorize them. I still play them, and I know them all very well, the records from the 1920s by Bix Beiderbecke and Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, and all kinds of people. That was maybe the bigger influence, even, than my Uncle Anton, because it—it got me right into this kind of music at a very impressionable age.

Josephine Reed: Can you remember the feeling you had when you first heard jazz?

Dick Hyman: The first recordings that my brother brought home from college, played for me, and gave me to understand that they were going to be very important, were recordings of Bix Beiderbecke, who was a trumpeter of the 1920s.

<music up>

Dick Hyman: Those were the first recordings. But then we branched out, and now that I look back at it, I can see he was really instilling a whole curiosity and reverence and appreciation of jazz, and I continued my interest in the whole music and the whole phenomenon. It’s really guided me through my life, the whole study of jazz. And of course, it worked very well with my peculiar talent, which is that I improvise very well.

Josephine Reed: How did you learn how to play jazz?

Dick Hyman: By listening to these records. And by being guided, first by my brother, then other musicians I was fortunate enough to play with as a kid, and by experience. And it was fortunate for me that all of this was centered in New York City, and I was there, at least on the edge of it.

Josephine Reed: And you went to college in New York City.

Dick Hyman: Yes. I went to Columbia, and it was a very easy transition from being a college student in New York to being a—a working musician. Columbia was a very good school in a lot of ways. First of all, it was in New York, so I could go down and hear—hear people playing on 52nd Street or in Greenwich Village. But in the college itself, I got to write a varsity show and play one, maybe two others as the second pianist.

Josephine Reed: You studied with Teddy Wilson. How did that come about?

Dick Hyman: When I was in college, a local radio station, WOV in New York, decided to have a—a jazz piano contest. I went down, and I won the thing. The prize for that contest, for winning that contest, was 12 lessons with Teddy Wilson. And I did study with him. He was very influential. I remember one time I asked him why it was that, although it seemed to me I was playing fairly well on some days, on the next day, I might be playing very poorly. And he said, “That’s why you practice,” which was a life lesson I’ve never forgotten.

Josephine Reed: You were playing professionally, too, around New York at this time?

Dick Hyman: Yes, at times I did play, and it was easy to make the transition into going after more serious, professional playing.

Josephine Reed: What was your first professional job?

Dick Hyman: Well the first job, actually, the first—the first job I had when I graduated, and got married, incidentally, around the same time, was playing in Harlem at a place called Welles Music Bar, which was on 7th Avenue and 132nd Street. And I went directly from our honeymoon weekend into Welles, met a lot of people there, a lot of other players and a lot of other jazz sort of people.

Josephine Reed: What was the jazz scene like in New York then?

Dick Hyman: Well, it varied, you know. It was a lot grimmer than I realized at the time. There was all kinds of—of problems with the police department and drugs, and race things. But I was young and uninformed, and I just sailed on through it. For me, it was a lovely time. We’d go up to Welles, and I would play until 3:30 or 4:00, and that was kind of normal for places. And that led to other jobs. Of course, I was becoming connected with jazz people. There is a distinction between jazz people and the people who are not jazz people, who can be close friends and very proficient. But the jazz community is something else. You all recognize that—among each other, that you have certain improvisatory gifts. And I began to know people and to work particularly with Tony Scott, who was a wonderful clarinetist at that time. And he got me to play with him at a club called Café Society Downtown. It was in Café Society that I was able to hear Art Tatum close up. He was the feature for two or three weeks. And Art Tatum was the greatest pianist there ever has been in jazz. He’s the ideal of most of us in the field, then and, I suspect, now, did see him there and talk with him, occasionally. It was like talking with a god.

Josephine Reed: One thing led to another, and at the age of 23, Dick Hyman found himself on tour with Benny Goodman.

Dick Hyman: I was recommended to play with his—one of his sextets, and we went on a European tour. This was 1950. And we played all the—all the places in Europe, and in Italy and in France and in Scandinavia, at any rate. And I stayed in connection with Benny thereafter. And, occasionally, I would get a call from him to play a particular date with him, or a recording, or something or other. He was another great guiding post of my career.

Josephine Reed: How did you hook up in the first place?

Dick Hyman: I think it was just word of mouth, I was recommended. Benny was always changing personnel. That was one his most noticeable peculiarities, and he had a number of them. And it got to be my turn at a certain point. At any rate, that—that tour lasted, I don’t know, a month or maybe six weeks.

Josephine Reed: You must have learned so much in that six-week tour.

Dick Hyman: Yeah. I—I did learn. What did I learn? Well, I learned about the grueling nature of tours, of—of music tours in general, not just jazz. Having to get on a plane or a train, or something in between each one, and show up the next day and give your best for another performance, it can be very grueling for—after a while. And I admire people who do that mostly for a living. I did not want to do that mostly for a living.

Josephine Reed: As performers know, it’s a tricky piece of business to be a working musician and support yourself if you don’t want to tour… But Dick Hyman found a way out…

Dick Hyman: What was happening in New York was that the record business was beginning to boom. Everybody was recording. Record companies were having a wonderful time, and there were all sorts of freelance recording opportunities, and I began to record under my own name, too, solo piano things, or things with little bands. And along with that was the fact that each of the networks in New York had a staff orchestra—CBS, ABC, and NBC, where I joined and stayed for five years, was a tremendous orchestra, because it encompassed the NBC Symphony. But in addition to the symphonic people, they had music for other sorts of occasions, too, and I joined primarily to work an early morning breakfast show live at 7:05 in the morning. So, we would play early morning radio, and then some of us would be scheduled to play a little later in the morning, another breakfast show and we’d rush up to the NBC television studios and get involved in a show with Morey Amsterdam, which was called Breakfast with Music. At NBC, it fell to me to learn organ, a Hammond organ. After a bit, they had me doing game shows in the—in the style of those days, and soap operas.

Josephine Reed: It was almost like touring within New York City.

Dick Hyman: Well, that was the point, and that’s what I early on recognized was the better course for me. I can see now where my activities were really beginning to split. On the one hand, there was the—the jazz people and the jazz gigs and jazz recordings. On the other hand, it was studio work, which could be almost anything.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: Do you think because you were doing that studio work, that that sort of helped with your versatility when you did jazz?

Dick Hyman: Oh, undoubtedly. The—the point of my career then, and maybe still, is versatility. Maybe a little less now. I’m—I’m not trying to prove how versatile I can be anymore, but at that time, I really was. And I not only didn’t mind, but I relished peculiar difference of things that I might get to do in one day, from playing a soap opera or game show organ, to doing a jazz recording.

Josephine Reed: There’s the studio part of your life and the jazz part of your life. And what’s happening in jazz, or what’s really happened, is bebop has exploded.

Dick Hyman: Yeah.

Josephine Reed: As exemplified by Parker and Gillespie. What did that mean for your playing and how you approached the piano?

Dick Hyman: Well, I had to learn, as we all had to learn, what it was the very, very new way of playing that both of those people represented, Parker and Gillespie, and the whole bebop movement. It was a different language, and you had to learn that, and—and I was willing to do that. Some people didn’t. Some people wanted to stay in the 1920s. Some people wanted to stay in the 1930s. It was fine with me to go on and see what was happening right then.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: You played at Birdland practically from the time it opened its doors. Did you know Charlie Parker?

Dick Hyman: Charlie Parker, I didn’t know very well. I met him, and I played with him once or twice. I was playing the opening weeks in Birdland when we opened in December 1949. It was a panorama of the history of jazz. The opening act was an old-time Dixieland band, and I fit in there. And at the other end of the spectrum, was Lennie Tristano, who played a wonderful kind of jazz, which remains among the most progressive sorts of music that you can find. And there was Lester Young, and I was asked to accompany him. So I did double-duty on that show, from being in the Dixieland band to being in sort of a swing rhythm section for Lester Young.

Josephine Reed: Was it thrilling for you to be at Birdland?

Dick Hyman: Absolutely. It was thrilling. To work with Charlie Parker, even—even that one or two times, and Dizzy once or twice here and there, it was—was thrilling. You know, those are histor—historical people.

Josephine Reed: Did you feel that at the time?

Dick Hyman: Yes. Yes. Absolutely. And if you listen to what they’re playing you can just see the marvelous creativity of both of those guys, but in particular, Charlie Parker.

Josephine Reed: You recorded an album called A Child is Born, which is a song by Thad Jones that you play in the style of 11 different pianists. It’s quite a range, from Scott Joplin to Cecil Taylor.

Dick Hyman: Well, it’s clear I was trying to present myself as Mr. Eclectic. And it worked pretty well. I—I got some of them kind of okay.

Josephine Reed: Well, you can play in many, many styles, but you also have your own style.

Dick Hyman: Well, that’s the thing. That’s the thing why I—I look back on that album as not quite a totally wonderful achievement. Because after a while, I decided I’d get out of the business of trying to play like everybody else and begin to explore what it was I might do that was a little bit original. And since then, I’ve been working more on that.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: And how did you develop your own style of playing?

Dick Hyman: Like Teddy Wilson said, by get—sitting down at the piano and doing it.

Josephine Reed: You moved into arranging. Did you learn it on your own, trial and error? How did you go about figuring out what that meant?

Dick Hyman: It’s a little easier for a pianist to become an arranger, because arranging is an organization of music which is almost completely played in a performance on piano. If you know your way around the piano, you pretty much have an insight into the way the rest of the orchestra works. And, again, because I’d been a sideman on so many occasions of different kinds of music, it wasn’t weird to be asked to arrange, and that came along with the territory, really.

Josephine Reed: You played with bands that backed some of the truly great singers and arranged some of their songs, as well. Did you arrange for Lee Wiley?

Dick Hyman: I did. We made a nice album with Lee Wi—Wiley. I was the arranger and music director on that. She was very influential on a lot of other singers.

<music up>

Dick Hyman: And she expressed a jazz way of doing things, vocally. And not all singers do that—some of the singers come from a different sort of a vocal background. She came from a jazz background. I did similar things for Rosemary Clooney, Tony Bennett.

Josephine Reed: Did you enjoy working with singers?

Dick Hyman: Oh, sure. Yeah. Working with singers is a great deal of what a piano player or a piano player/arranger gets to do in this career. And what it means is that you are the adviser to the singer, if he or she needs advice. You rehearse, you—you maybe have a hand in the selection of tunes, although very often, the tunes are selected already, and you’re assigned to orchestrate them. But still, there are rehearsals and changes to be made. What is the right tempo? What is the right key? Shall we have strings or not? Is this going to be a big orchestra, a small orchestra? A lot of technical questions you have to work out with the singer. And then you have to conduct the orchestra in the recording studio. And then, of course, being in that position can lead to other sorts of live performance, concert performances.

Josephine Reed: You did a series of solo albums devoted to composers like Gershwin, Cole Porter, Harold Arlen.

Dick Hyman: Yeah.

Josephine Reed: And Duke Ellington. And I think I’m curious, thinking about what you said about Lee Wiley, she was a jazz singer—Duke Ellington, is the jazz composer here. The others write music that obviously can be put into a jazz idiom, but Ellington was the jazz guy. Can you tell me a little bit about you working with his music?

Dick Hyman: Ellington was unique. He had this band from his earliest days of very talented musicians, and the band stayed with him throughout his career. Some of the people there, like Harry Carney, were actually friends who had played with him for 40 years and more. He composed things on the keyboard, or he composed things for the band directly. He had a very individual way of looking at things, and his pieces, they set the standards, really, for jazz compositions.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: And then something new came onto the musical scene: the Moog synthesizer, and Dick Hyman was one of the first people to record with it.

Dick Hyman: It was so interesting to work with because it gave you a range of musical possibilities that even a pipe organ would not have been able to do.

<music up>

Dick Hyman: On the other hand, it was limited to one tone at a time, so you couldn’t do a full performance on it, except by overdubbing, by playing along with yourself on previous recorded tracks. It was not unlike the electric organs that I had played. In fact, that was my chief entry into it, electronic sounds that you could modify and play in various interesting ways. But with the Moog, there are a lot of possibilities that are simply—didn’t exist in other keyboards. You could glissando. You could go from a low note to a high note without the individual tones, so that you’d go (sings a glissando), and you can control the rate of the ascent or the descent. And all sorts of—of manners of producing a tone, and once we got into it, it was the most interesting thing. And I did two albums on the Moog. But it—it should be said, again, that it was not an organ. You could not make a finished performance on it. You had to use it several times over in sequence. And occasionally, and I did this, prepare the accompaniment of say, piano, bass, and drums beforehand, and then overdub the instrument one or two tracks above.

Josephine Reed: How did you move into composing for the screen?

Dick Hyman: Well, it was an out—an outgrowth of working with singers, with orchestras, with this and that. It just seemed a natural evolution of things. I did several films bef—before I began to work for Woody Allen. It was just one more thing you could do in the studios.

Josephine Reed: Where do you come in to the process, or does that change from film to film, director to director?

Dick Hyman: Well, it changes very much with people’s different approach to how to do this.

Josephine Reed: Let’s take Woody Allen.

Dick Hyman: Well, the idea, first of all is, is there a musical scene? That determines a lot of the other music. It determines what you have leading into it, leading out of it. Then the other great point of film music is, what is the viewer supposed to be feeling?

<music up>

Dick Hyman: You are supposed to provide a soundtrack for his emotions, and so is it a sad scene, a comic scene? Does it require a commentary by the orchestra, or should the orchestra be playing music you’re largely unaware of, but is influencing your reception of the drama? These are all questions that you work out with the director, who may have some definite ideas. But the composer can bring some points of view that the director might not have thought of, so that you must have a meeting of the minds and a confidence in—in each other’s approach. And sometimes you get it right, and sometimes you don’t. But mostly, you get it right, or you won’t be hired the next time.

Josephine Reed: You perform quite a bit now, and you’re usually playing solo piano.

Dick Hyman: Yeah. Well, in recent years, I’ve settled into a lot more performing and I’ve—I’ve become—become more concentrated on my solo playing, and I like that very much.

Josephine Reed: Two things: One, what do you like about playing solo? And the second is, how has your playing changed throughout the years, your performing?

Dick Hyman: Well, I think by now, my playing has changed a bit. While I will still play, on request, any of the earlier old-time stride or rag pieces that people want, I’m really interested more in playing improvs, because I think that’s where I do my best work. In the kind of music we are involved in, we have the privilege of changing from performance to performance. It isn’t doing the same Beethoven sonata in the same way. We get an idea, work things out on the spot. To me, that’s the biggest incentive. To get an idea and work it out on the spot, and to give yourself some latitude.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: What do you like about the solo recital?

Dick Hyman: Well, a solo recital, it’s all up to you. It isn’t totally about piano playing, though you do have to have some kind of a sympathetic relationship with the audience, and I’ve learned enough to have that. There are times when you can sit down, and almost anything you play will sound fine. And the other times, you’re struggling, because you haven’t played enough at the keyboard for a few days, and it comes out.

Josephine Reed: How much do you practice a day?

Dick Hyman: Well, I don’t practice a great deal, but I have to practice every day. I mean, it might be 20 minutes, a half-hour, an hour, unless I’m getting ready for a particular vehicle, in which—you know, it might be more. But on the whole, just have to say hello to the piano.

Josephine Reed: That’s a nice image. You created and headed Jazz in July at the 92nd Street Y. You were in charge. You were the artistic director for two decades. What is that program, and what is it that you wanted to accomplish with it?

Dick Hyman: Along with Hadassah Markson, who was the producer, the idea was to have, for the first time, a jazz series at the 92nd Street Y, to present, in a concert form, the jazz that you might or might not expect to hear in a nightclub or concert situation. I was connected well enough with the jazz communities in New York and—and somewhat in California, that we can get performers and put them together in interesting ways. After 20 years, I didn’t want to do it anymore, but it is now in the hands of Bill Charlap, who continues that tradition wonderfully.

Josephine Reed: You have worn so many hats. Is there one that you enjoy more than another?

Dick Hyman: What I really like, at the core of everything, it’s—it’s playing solo piano. That’s what I do more and more. The other stuff is frequently interesting and fun, and it gives you a sense of achievement. But it—it—it starts, really, and apparently it ends that way, too, with being a solo pianist.

Josephine Reed: And, to be named a 2017 NEA Jazz Master, what does that mean to you?

Dick Hyman: It’s—it—it—it means a great deal to me. It is marvelous to be named an NEA Jazz Master. It’s an honor that I couldn’t have ever expected. I’m really thrilled and honored to be recognized for whatever it is that I’ve achieved. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that. Especially because I’ve gotten so ancient, and to have that award at the time of my 90th birthday is something I can’t express how wonderful I feel about that.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: That’s pianist and 2017 NEA Jazz Master, Dick Hyman. You've been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

<music up>