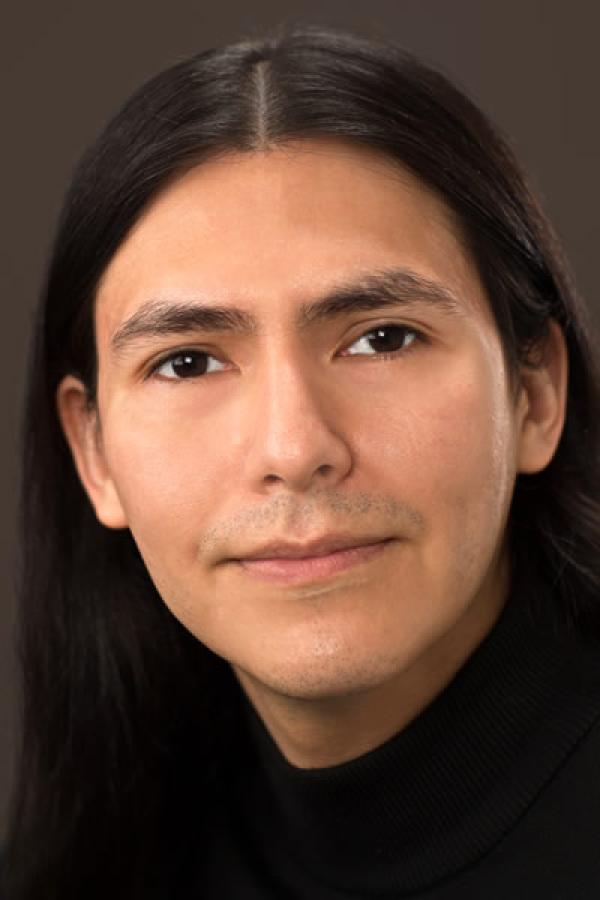

Benjamin Garcia

Photo by Linda Le Photography

Bio

Benjamin Garcia’s first collection, Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions, 2020), was selected for the National Poetry Series by Kazim Ali. This collection won the Eugene Paul Nassar Poetry Prize and was a finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. His poems and essays have recently appeared or are forthcoming in AGNI, American Poetry Review, Kenyon Review, and New England Review. His video poem “Ode to the Peacock” is available for viewing at the Broad Museum’s website as part of El Poder de la Poesia: Latinx Voices in Response to HIV/AIDS.

Garcia is grateful to various communities and the devoted individuals who make them possible, among them: Lambda Literary, CantoMundo, the Frost Place, Alma College, Cornell University, the University of New Mexico, among others. He works as a sexual health and harm reduction educator in New York’s Finger Lakes region, where he received the Jill Gonzalez Health Educator Award recognizing contributions to HIV treatment and prevention. He serves as core faculty at Alma College’s low-residency MFA program and is currently working on new projects in both poetry and prose.

I like to say that my mother lives in the house that words bought. It’s not a pretty house, clad in shiplap siding that flakes lime green paint chips. My little brother calls it the Granny Smith. But it’s what I could afford through extremely frugal living during my graduate and post-graduate fellowship years at Cornell University more than a decade ago. I came up with that name because, at the time, it seemed absurd to me that words could have such a tangible end.

Years later, helping my mother clean this house—the house words bought—I happened upon a letter from my grandfather, Apolinar, sent from Rawlings, Wyoming, dated November 27th, 1978 (exactly 44 years to the day of me writing this entry). The letter addresses his oldest son in Mexico, to whom he sends money earned as a sheep herder. With no surviving photographs, and because my grandfather died before we met, this was the first time I felt connected to him through a physical artifact. Green ink on yellowed sheets of lined paper.

When I show my mother the letter, I comment on his striking penmanship—so much more pleasant than my own. She laughs, and when I don’t understand, she spells it out: your abuelo Apolinar couldn’t read or write. He more than likely paid a scribe after dictating this letter. And the rope connecting us is ripped from my hands, but also complicated in new ways I am still unraveling.

I am astonished now by the National Endowment for the Arts letter as I was then by my grandfather’s. I don’t know what this green ink on paper means. What I do know is that this funding will grant me what most artists and immigrants want, which is the freedom to keep working.