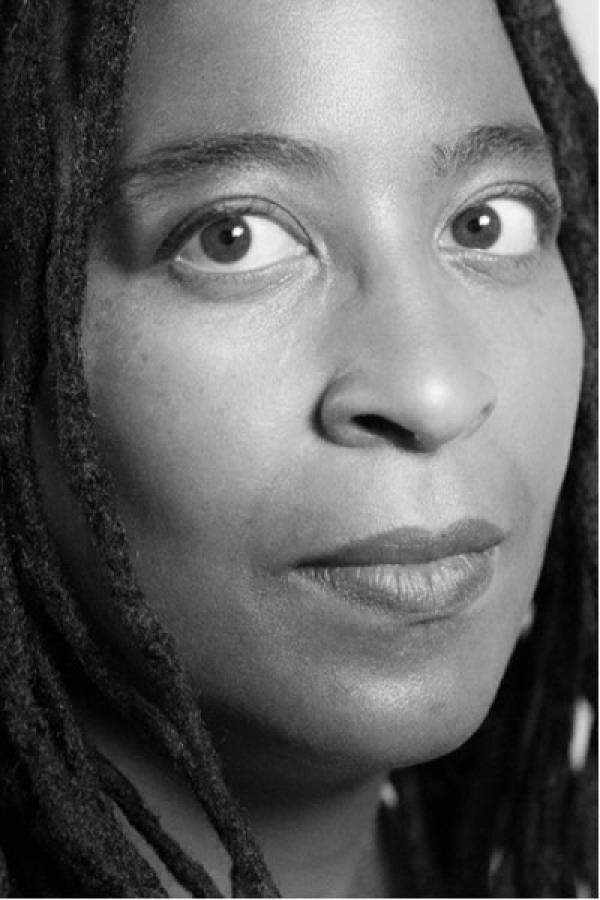

Camille T. Dungy

Photo by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Bio

Camille T. Dungy is the author the essay collection Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys into Race, Motherhood and History (W.W. Norton, 2017), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and four collections of poetry, most recently Trophic Cascade (Wesleyan UP, 2017). She has also edited anthologies including Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. Her honors include NEA Fellowships in both poetry (2003) and prose (2018), an American Book Award, two Northern California Book Awards, and two NAACP Image Award nominations. She is a professor at Colorado State University.

I hope we’re not past a moment when grand ambitions can find concrete and practical support. In all of my books, I have written about how people have survived and thrived through contemporary and historical struggles. It is often difficult writing, but I hope that these stories reach people who need them, who will be moved by them, who will use them to help build a less hurtful world. Writing is mostly a solitary pursuit. I sit in my room, in the quiet of my own mind, organizing and re-organizing words on a page. If I consider audience, that comes later—in the moment when I submit my work to the world and hope it will move readers. This is the second NEA fellowships I have received. The other, in poetry, also came when I was new to publishing in the genre. How grateful I am for this recognition! How grateful I am to have worked so long in this solitary art and then, upon making the work public, to receive such concrete and practical support. This fellowship rewards the hope I held and the risks I have taken on the page. This fellowship has galvanized me both times I have received it. Writing as I so often do about survival, this NEA fellowship has provided me with the support necessary for resistance, renewal, and sustaining hope.

Excerpt from "A Brief History of Near and Actual Losses"

We are at Cape Coast Castle, and Callie refuses to be held. She won’t let me carry her in my arms. She won’t let me put her in the cloth carrier on my back. She won’t ride on her father’s shoulders. She won’t sit astride my hip. She wants to be in charge of exactly where her body goes. She wants both feet on the ground.

I don’t want her feet on the ground. The floors of the slave dungeons are caked five to seven inches deep with centuries of hard-packed dirt and sweat and human waste. In one chamber, a drainage canal has been dug to reveal the brick half a foot below. This way, visitors to the former slave-trading outpost on the west coast of Ghana can more fully visualize what constitutes the floor under our feet. What kind of mother would freely let her child walk on such filth? I try to hold her off of the floor, but Callie wiggles out of my arms and runs in circles around her father, our guide, and me, giving the soles of her tiny Keens maximum exposure to the nasty ground. Again and again I try to pick up my daughter. Again and again, she makes it clear she will not be carried anywhere against her will.

It is the middle of May 2013. It is three weeks before my daughter’s third birthday and 206 years since the British Parliament passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, in March of 1807. The dungeons are museum installations now, part of a series of UNESCO World Heritage Sites dotting the Ghanaian coast. Our guide tells us the castle serves, today, to remind people of the horrors of the Atlantic slave trade and to caution us to treat one another better this time around. To never let slavery happen again. I can’t find the energy to remind him that people are still at risk, still being shipped away for profit, every minute, every day. My daughter, running circles around me in her babyGap shorts, is driving me to distraction.

The exterior walls of Cape Coast Castle are brightly whitewashed, so when we walk out of the tropical sun into the male slave dungeons—chambers that are essentially windowless and purposefully dank—we are blinded by the darkness of the place. For extra shock value, our guide turns off a chamber’s one dim bulb. This is to help us imagine something even more horrible than what we can already see.

“I don’t like it here,” Callie says. “I want to get out of this place.”

Our guide turns the light back on, acknowledges how uncomfortable these dungeons are. My family is alone with him in this room, having chosen to pay more for a private tour. The guide assigned to us has been leading these tours for many years and is personable and quietly authoritative. He understands what we want from this experience. He asks us to imagine being packed in here with two hundred men, shackled and naked. He asks us to imagine the stench, the vomit, the sounds of writhing bodies, chains drawn against chains. I grab hold of my daughter for a moment. Callie wiggles out of my arms and nearly evades me, but I grip her hand and keep her near. “Shh,” I say. “This is a sacred space. Be still.”

(Excerpt is from Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys into Race, Motherhood, and History)