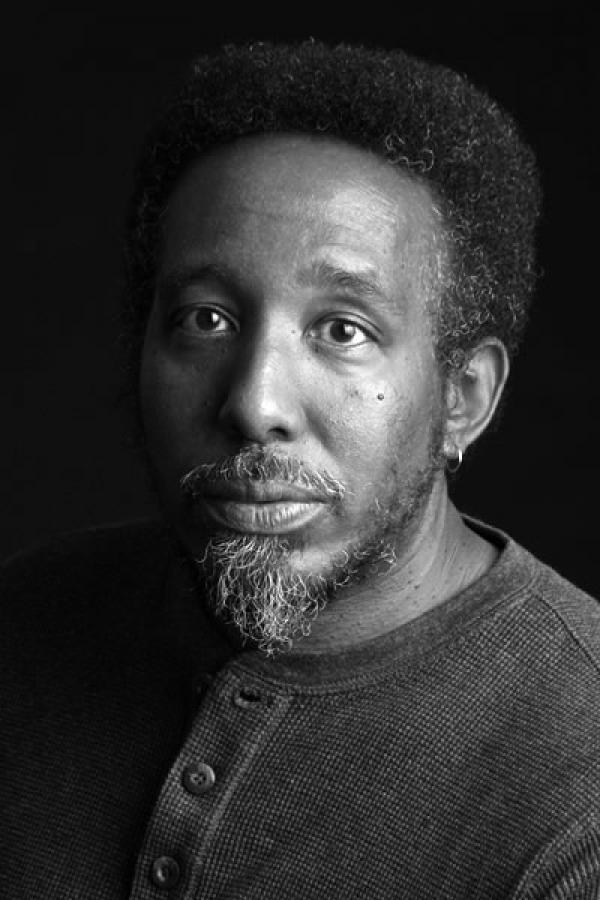

Frank Wilderson

Photo by John L. Blum

Bio

Frank B. Wilderson, III's memoir, Incognegro: A Memoir of Exile and Apartheid (South End Press, 2008), the story of his life as one of two Black Americans to hold elected office in the African National Congress and of his political maturation in the U.S., won the American Book Award, the Eisner Prize for Creative Achievement of the Highest Order, the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award in Nonfiction, and was a finalist for ForeWord Magazine's Book of the Year (nonfiction category). He is the author of Red, White, & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Duke University Press, 2010); and is working on a documentary Reparations…Now. His creative writing has appeared in journals such as Konch, Callaloo, Obsidian II, Paris Transcontinental, and The Yardbird Press Anthology. He is a recipient of the Crothers Short Prose Award, the Judith Stronach Award for Poetry, the Jerome Foundation Artists and Writers Award, the Loft-McKnight Award for Best Prose in the State of Minnesota, and the Maya Angelou Award for Best Fiction Portraying the Black Experience in America. He holds an AB from Dartmouth College, an MFA from Columbia University in New York, and an MA and PhD in Rhetoric and Film Studies from UC Berkeley. He teaches African American Studies and Drama at UC Irvine.

Author's Statement

When a person is both a creative writer and an academic, he or she is tempted to treat rigorous interrogation of the imagination--that is to say, creative writing--as a sideline, something of less value and importance than the completion of an article or a book grounded in post-structuralist theory. As an academic, I know where to go and what to do for a pat on the head. Writing a memoir, or a novel, or a short story, however, is the road less traveled by, and I have had to work as hard on my creative writing as on my critical theory without the promise of acceptance for my creative work. This is why I am deeply grateful to the NEA and the panel of esteemed judges for this award: you have validated my second job and my first love. At one time I was told that I should become a suspense writer. At another time I was told that I should become an intellectual. I have never seen these two endeavors as being mutually exclusive, and have struggled in my own private way against the false dichotomy. This grant will give me the opportunity to continue to fuse these seemingly disparate endeavors in my own voice. The NEA Fellowship will help me complete a novel-in-progress, The Children of Lovers, which explores the tension between personal desire and commitment to political struggle. With this money I will be able to embark upon extensive research and carve out writing time and space that will allow me to more easily shift from the kind of thinking required for academic writing to that required for creative work.

From the memoir Incognegro

The population in the taxi has dwindled to three. A nursing sister with tired feet, judging from her weary eyes; another woman much younger than I but obviously no longer in school; and myself. Now, Sipho's eyes and mine meet more frequently than before. Time and again he checks his rear view mirror. He stops to let the nurse out. I don't even bother to check the kombi behind us. It's still there. It has to be. It's come this far. What can I do but see this thing through? Bolt now? Jump out with the nurse and run away? I don't even know where I am.

The door of the kombi slides open. The nurse gets out. For a moment she looks at me. I look away. She slides the door shut. The kombi sputters, coughs, jerks back onto the road. We are off again.

It's been more than a year since I last spoke with my father. Unable to stomach the smooth mendacity of our family, I left without saying goodbye; no more than a message on his answering machine: Tomorrow I am moving to South Africa. Good-bye. Now, I wonder who will take it upon themselves to explain my death to him, make it comprehensible, put it in its proper context. What will my body look like when it finally reaches him? Assuming it reaches him.

The young woman next to me slides her hand across the seat and holds mine. I give a start, but know better than to turn my head in her direction. Through my peripheral vision I see her looking out the window.

"Dankie, driver!" [Next stop please!]

The kombi hobbles to a halt for her. She crawls over me, slides the door open and gets out. The kombi that's been following us draws up to our fender. Sipho stares at me in the rear view mirror. I hear the idling engine of the kombi behind us. The young woman starts to cross the road. She has left the door open. I have yet to move.

Safely on the other side she turns and yells: "Aren't you coming?"

Sipho looks at her, then at me.

"This is the stop you wanted," she yells, "come on! Get out of the kombi."

Sipho waves a warning finger at her: "Hey sisi! Mind your own business. He wants Unit 6."

"No, Tata this is his stop," she yells, firmly, but reverently.

I hear the doors of the kombi in back opening. Someone next to it yells, "Mind your own business, bitch!"

"It's true," I tell Sipho sensing that this, the moment of indecisiveness on all sides save the young woman's, is the time to act. I slide toward the door. "While you were getting petrol, I told her where I was going and she said it wasn't Unit 6 at all--that she'd let me know when we got there."

"Hey!" he yells at me as my foot dangles out the door, "Hey, induna! Get back in here."

The young woman continues to yell: "Why do you want to take him somewhere he doesn't want to go?" Her voice is gathering onlookers. They stop and cluster around her. Some have started to come out of their homes. From the kombi in back someone yells, "I'll moer you bitch!

"Tata, why must you abuse me?" she asks. "I'm merely trying to help this man find his friend." Then to me: "Come brother, cross the road. It's ok, cross the road. These people know where you're going. We'll all help you find your way," to the others, "won't we?" None of them seem too eager.

My legs are jelly as I stand on the gravel. In a split second I decide not to close the door behind me. Make no wasted movements. To my left, the men from the other kombi glare but don't approach. From the graveled shoulder I light upon the tarmac. I start to cross. What must it feel like, a bullet to the spine? What do you feel when the wound has healed? Numbness in the thighs? Feet forever floating in ether? A mouth that will not close? A hand that cannot write? Bowels that run at will? A life forever indebted to others?

Now, I am beside her, shaking.

"Walk forward," she says, "don't look back. If they see you're scared they'll come for you."

"Where are we going?" I ask.

She looks at me and says, "I don't know."