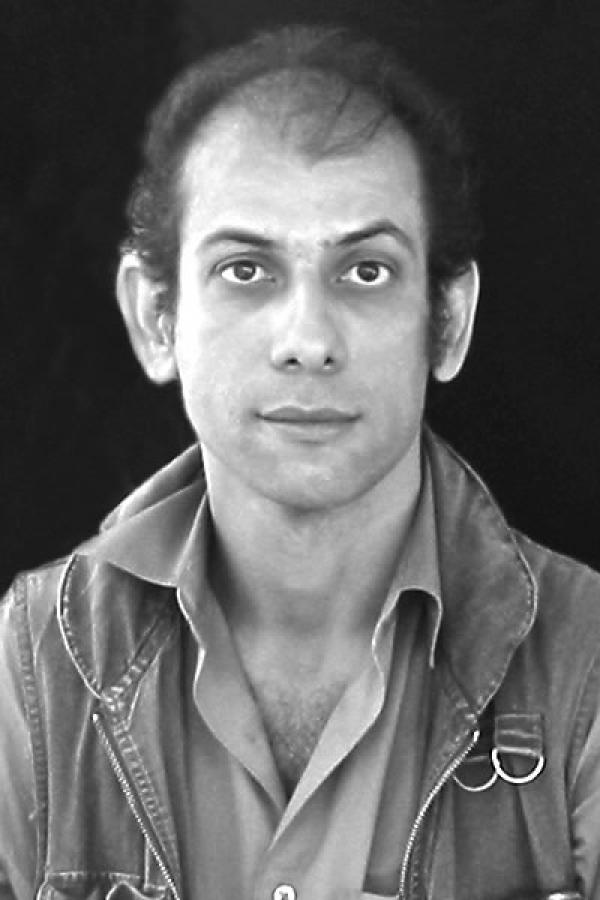

Salar Abdoh

Photo by Jaafar Modarres Sadeghi

Bio

Salar Abdoh's novels are The Poet Game (Picador, 2001), and Opium (Faber and Faber, 2004). His short stories, essays, and translations have appeared in various publications, including the New York Times, Bomb, and Callaloo, and in 2007 he was awarded the NYFA Fellowship. Born and raised in Iran, he lives with his family in New York City and teaches in the English department at The City College of the City University of New York.

Author's Statement

Winter is cruel on a motorcyclist in Tehran. I was doing research and living at the house of a writer friend in the Velenjak district. On top of several layers and a jacket, I also wore a dark green windbreaker. It was cheap material and I held little hope it would do me much good on the bike. The street had its own guard, a vet from the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. He'd endured the duration of the war, eight years, and lately his wife would no longer allow him to open the album of old photographs from his soldiering days. We talked often and drank weak tea together in his cramped guard's shack. He'd been hit with chemical weapons more than once, and his one big complaint was that he couldn't find an underarm deodorant that didn't give him terrible rashes. I gave him the 'natural' one I'd brought from America and that seemed to work. He was grateful. Yet the day he saw me with the cheap, dark green windbreaker his eyes went the proverbial thousand yards and he said, "They used to make us wear those when they thought we'd get hit with chemicals."

Aqa Iraj is my friend and his story is one among many. I am a writer for many reasons, I suppose. One of those reasons, I'm certain, is to give voice to the Aqa Iraj's of the world. To do so, I need to see the world and know its anguish. The NEA award buys time for a writer and allows him to go to the places he needs to go and see the things he needs to see. My thanks to the NEA for what it has done for us through the years.

From the short story "Water"

It started with him just saying those numbers, 2-3-1-9. When she asked what that was, he told her that that had been a hill in Kurdestan and that the two hills around it could have been 2320 and 2318 but not necessarily, no. He never once looked at Professor Elahi, but he did tell her about the kid who cried and cried, and how towards the end he even cried in his sleep and cried when he woke up and asked for his mother. He told her about how Brother Samanpur had put him in charge of water and how one of the other younger boys would follow him around when the time for water arrived hoping there would be a spill from the five drops of water he used to wet the wounded's lips with. He told her how he'd saved his arm after the cut was reopened. He'd fished for the vein himself, he said, then had the kid tie it with the string from his prayer beads. When she asked how that was possible, he said that everything was possible when the time for it came. A vein was flexible, he said. They'd taught them that at the First-Aid course at the Sanandaj military base. So he'd checked the infection by being resourceful. Everyday he'd clean around the wound, then have the kid tear off a piece of bandage until they were out of bandages and had to resort to Ebadi's own undershirt which they'd washed and let dry. He went on to tell about the grape leaves then. And about the day he'd noticed his hand covered with the huge green flies of Kurdestan. Some of the laid eggs, it seemed, had oozed beneath the bloody cloth into the wound. Afterwards he'd passed the time delicately digging them out with a thin piece of stick while he waited for the boy to get his courage up and apply fresh cloth. He told her all the things he'd told the boy about patience, though it hadn't done any good in the end because on day eleven when he was woken up by another platoon that had been sent to retake and lose 2319 he'd noticed that the boy was nowhere to be found.

"Where was he?"

"In the stream."

"Alive?"

"No."

"Do you think he did what you told him not to do? Did he go out there to get himself shot?"

"He may have. It was day eleven. Our own may have shot him by mistake. But I never wanted to ask them. And they never told. I was lucky I was asleep or they may have shot me too."

"Sleep with all that shooting around you?"

"You see, Miss, you don't know war. After a while you'll sleep through anything. You might even not sleep if there's no noise."

He could feel her consider this. Consider everything he'd said, in fact. Maybe she was speechless or she was imagining the miracle of a man saving his own hand with his prayer bead.

"I kept the beads," he said.

"And the kid?"

"What about him?"

"What was his name?"

"I don't know."

He could have lied and told her any name. But wouldn't that make his whole story a lie then? He'd told her all this to make a point: she shouldn't have been taking those foreign tourists around showing them war photographs. In a way that kid, too, was just another photograph now. Ebadi had woken up one day not remembering his name. How was that possible? After his hand had healed he'd even gone and visited the kid's people. They were small farmers who lived up in the north where water was plentiful. He'd eaten their food and slept in their house. He'd watched the mother and father cry. The brothers and sisters too. All six of them. They were a family of criers. How could he go back now and ask the boy's name? If only the boy had been more patient, or if only he'd been sleeping too on day eleven when 2319 had been retaken by their own.

"How can you not know his name?" she asked.