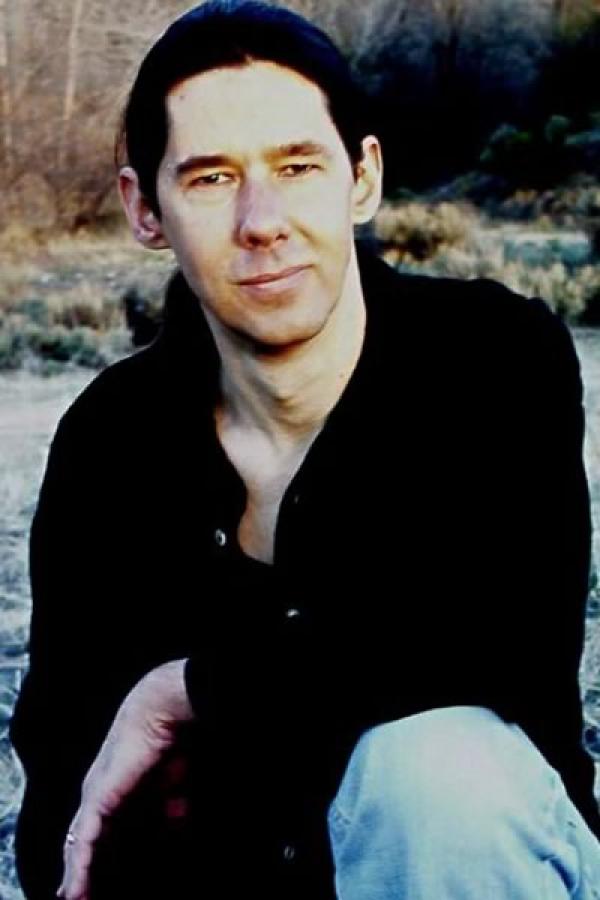

Sean W. Murphy

Photo by Tania Cassell

Bio

Sean W. Murphy is the author of three novels and one book of nonfiction. The latest edition of his One Bird, One Stone, a nonfiction chronicle of Zen in America (Hampton Roads 2013), won the 2014 International Book Award in the Eastern Religions category. The Time of New Weather was named Best Novel in the 2009 National Press Women's Communication Awards, while his debut, The Hope Valley Hubcap King, won the Hemingway Award for a First Novel and was an American Booksellers Association BookSense 76 recommended book. He is also the author of a third novel, The Finished Man. (All Bantam-Dell books). His novel-in-process, Wilson’s Way, won the 2014 Dana Award in the Novel, as well as the 2017 William Faulkner Wisdom Award for novel-in-progress. His essays, articles and short stories have been widely published and anthologized.

A recognized Zen meditation teacher (Dharma Holder) in the American White Plum Lineage, Sean has practiced Zen meditation for 30 years. He also teaches secular meditation through his nonprofit Sage Institute for Creativity and Consciousness, and has taught for many years with Natalie Goldberg in her series of independent writing and meditation seminars. He has taught meditation, creative writing, and literature for the University of New Mexico-Taos for 20 years, as well as for Southern Methodist University's Taos campus, the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, Naropa University in Boulder, and a variety of conferences and organizations, including a number of masters classes in the Novel. His yearly Write to the Finish course, taught with his wife Tania Casselle, who is also an author, has helped dozens of novelists and nonfiction writers finish book-length projects over the last ten years. Independent writing seminars through their Big Sky Writing Workshops have included residential courses at Casa del Sol in Ghost Ranch, Canyon de Chelly, the Murie Center in Grand Tetons National Park, Franklin University in Lugano, Switzerland, and the Summit Huts Association in Colorado, among others.

On a practical level, as university teacher and director of a nonprofit mindfulness and creativity organization which trains students to teach meditation skills to others, I have a very full schedule, and this fellowship affords me the opportunity to take a sabbatical to focus on my novel and other writing projects, for which I am very grateful!

On another level, as a mid-list author with four books published, receiving such national recognition reinforces my conviction that the work I’ve chosen to devote my life to is important, valued by not only my own community and readership, but by the larger society of which I am a part. This recognition has already proven to be an inspiration to my own students, who may perhaps be encouraged to keep doing their best at the work their heart calls them to do—for we never know when an unexpected door may open.

A writer, or any artist, has to find their own way in an unpredictable world. It is not, for most of us, a life that provides a great deal of certainty or security. The rewards, however, are enormous, and if we’re fortunate enough to find a readership, the rewards to them may be significant as well—I’ve received letters from readers saying that one of my books changed, or even saved, their lives. Books have often shown me new possibilities and restored my faith in life as well. So it’s important work we writers do, but at the same time it’s easy to fall into doubt, or to feel the world does not value what we do. So to receive such recognition is enormously encouraging, and my hope is that its effects may ripple out to others who struggle to make their voices heard, and inspire them as well.

Excerpt from Wilson's Way

In case you don’t believe the kid had a charmed life, consider this:

Wilson and his father reach the top of Black Ice Summit in a whiteout, and Dad can’t wait one more minute to relieve himself. He leaves the car running, flakes falling thick against the windscreen, wipers going thwack thwack thwack, giving young Wilson a momentary glimpse of Daddy as he struggles to undo his zip — snow already accumulating on his hair, shoulders, the windshield, blotting out the scene until the thwack thwack wipers reveal: there’s Daddy, visibly shivering, rummaging to pull crestfallen flesh from its cozy hiding place and out into the elements as quickly and carefully as possible. Flakes big as a quarter come down fast, swallowing the picture again till thwack thwack—Daddy stands, clear and still against the snow, arched a little backward, a steaming crescent of yellow streaming through the air in front of him, the only clear note of color in all that whiteness.

But then something strange starts to happen. Young Wilson feels it through the frame of the car, a shudder that builds until he looks around but can’t see a thing through the flat white of the back windows — then the whoosh of an oncoming semi sends up a whirl of snow as it skids round the top of the curve. It pushes the collar up against Dad’s neck, blows hair forward across his face: its wind tunnel tail lashes the old Chevy, shaking it from bumper to bonnet—and young Wilson feels something give way. The grip of wheels on ice, the set of the gears, friction of brake upon wheel—how can he, at age five, know what it is? But Wilson feels something begin to move.

Slowly at first, the car eases backward along the ice. The thwack thwack wipers reveal Dad doing a double take, eyes going wide as he glances back over his shoulder, like a character in an old black and white movie. Then he goes into a full-on Keystone Cop routine: the yellow stream sprays high, sprays low, sprays everywhere, as Wilson laughs in delight. After that, Dad simply pans out of the picture.

The car, pausing for a moment in its backward motion, begins to swivel and then ease forward, nosing down: the thwack thwack wiper blades reveal Daddy, now wheeling around the side of the car in speeded-up motion, sliding like a marionette on the ice—funny Daddy, he’s really hamming it up! A final yellow spurt comes from somewhere below his beltline as he tries to intercept the rolling car while tucking himself safely back into place.

And at the same moment, Dad of course must be able to glimpse young Wilson as the car rolls back, out of his reach and onto the blacktop, every time the thwack thwack of the wipers, just for an instant, clears the windshield. There he sees his only son, his baby boy, standing up in the front seat to his full three-foot height, the better to see what's happening, hands gripping the rim of the wooden dashboard, a grin of delight spread across his features. Each thwack thwack reveals the boy's face for a moment between windshield whiteouts, like frames from a film, each one a little smaller, a little further off, as the car backs away in a naturally occurring zoom-out...