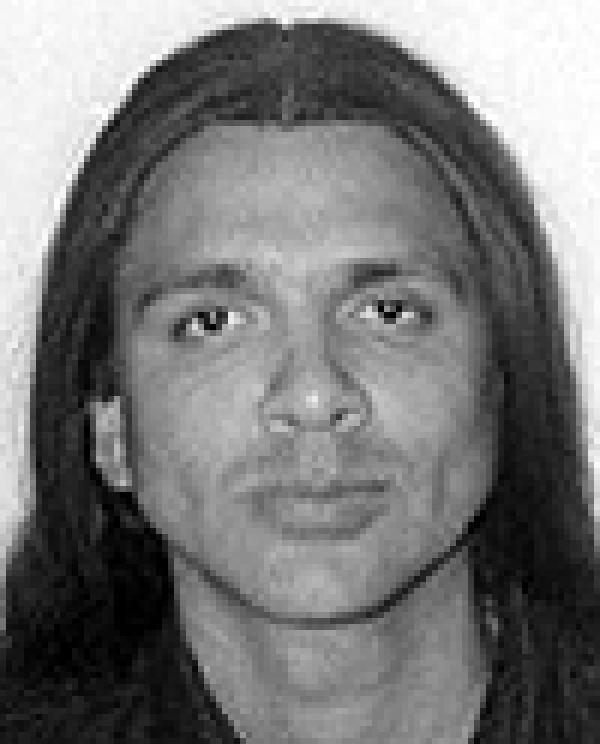

Stephen Jones

Bio

I'm 30, an Assistant Professor at Texas Tech, live in Shallowater, TX, and would very much like to take the world over with (my) prose.Author's Statement

Cliff Becker's call to me was a roundabout e-mail, as I'd evidently thought this NEA grant was such a longshot I'd just made up a phone number of some place I would maybe like to live. The address wasn't quite valid either. Hopefully at least the zip- and area-codes matched, though. I mean, I am a fiction writer. Telling compelling lies in a compelling manner is supposed to be what I do.

The half-truth excerpted above is of course from my The Bird is Gone, now subtitled A Manifesto. Thanks to this grant, too, it's a done deal, already getting rejections. One of them calls it a 'comic-strip narrative,' which is a pretty good description: it has a glossary, appendices, footnotes; all these nested investigations and disparate narrative voices; partial radio-transcriptions of legendary basketball games; notebooks of notes a custodian writes in his closet at night with a pencil almost sharp enough to thread it all together. Like any good comic book, too, it's fantasticãor, specifically, speculative, as in speculative fiction, sf, set in a future America in which Congress, under pressure from Keep America Beautiful Too, has signed into law a conservation act meant to restore all indigenous flora and fauna to the Great Plains. Problem is, Indians are still on the books with mountain lions and coyotes, as bounty. Meaning they qualify as part of this 'fauna.' So, overnight, the Great Plains are Indian again. Now fast-forward fourteen years to a small bowling alley - Fool's Hip - and its stock of regulars: LP Deal, the custodian; Mary Boy, the red Catholic; Back Iron, the cross-dressing ex-basketball star; Denim Horse, the bowling pro lifted right off the cover of a romance novel; Nickel Eye, the first Indian serial killer; Owen82, the dead basketball coach; Cat Stand, named after a roadside bordello; Enil Anderson, the Nordic tourist; Bacteen the trickster, Smudge the medicine man, Special Agent Chassis Jones, Nathaniel Hybird the dairy hauler; Miss America. The Lone Ranger's even there, the tan lines crisp across his cheekbones, and then there are all these Indians dressed up as John Wayne, their hair tucked up under their hats. Now, just leave one of these people dead in a ditch, lock the door (more or less), and you've got a Red whodunit, with various asides, parentheticals, etceteras, etc. It's kind of a follow-up to my The Fast Red Road - A Plainsong (FC2, 2000; Independent Publishers Award for Multicultural Fiction), only, at about 200 pages, it's faster.

from The Bird Is Gone

LP DEAL, five-ten in boots, but then he can't wear boots at work, either, as part of his job is traipsing down the alleys to retrieve busted pins, motionless balls, the occasional beer bottle. Once a prosthetic arm. Fool's Hip gives mercy strikes if your arm falls off mid-bowl, but the limit is three per game; some of the veterans were taking advantage. LP tried wearing a pair of the house moccasins when he first signed on, hand-sewn the old way, from the soft leather interior of thousands of abandoned golf bags, but found he couldn't stand up on the waxed lanes. It was funny for a while, but then he had work to do. Now he wears simple canvas basketball shoes - standard Indian issue - dingy grey at the toes from mopping afterhours, and monochromatic coveralls, once brown but long since gone tan, from washing them every night in the dishwasher with the last load of the night, steam filling the room, scouring his lungs. Sometimes, standing there naked and blurry, he sings, his voice resounding off the stainless steel kitchen, over the polished counter, spilling out into the hardwood lanes, but then other times he just stares at his indistinct reflection, the roadburn all down his left side expanding in the heat.

On his application for employment, under Tribal Affiliation, he checked Anasazi - a box he had to draw himself - and under the story and circumstances of his name, he recounted what he could remember of the Skin Parade fourteen years ago, when he was twelve. Him and his mom had been hunting and gathering at the supermart in Hoopa, California when the wall of television sets said it, that the Dakotas were Indian again, look out, and three weeks and two and a half cars later, LP and his mom rolled across the Little Missouri at Camp Crook with nearly four million other Indians. It wasn't the Little Missouri anymore, though, but something hard to pronounce, in Lakota. The grass was still black then, from the fires . When LP and his mom ran out of gas they just coasted through town, and when they finally rolled to a stop, it was in front of a record store, florescent letters splashed onto the plate glass. For a moment LP could have been either LP Deal or Vinyl Daze, but then in a rush of nostalgia his mom took the second name. Within a week the guys at the bar were calling her VD. LP didn't get it until years later, months after he'd lost track of her at one of the pandances, and by then he was old enough to pretend not to care.

He did cut his hair off when he got home that night, though, part of the Code, and hasn't let it grow back yet, wears it blocked off at the collar instead, muskrat - slick on top. His right hand is forever greasy from smoothing it back, out of his eyes. Mary Boy, LP's boss, offered him a hairnet in passing once, but LP declined: by then he'd grown accustomed to the ducking motion necessary to smooth it down. Had come to depend on it, even, as cover for leaning down to the inside of his left wrist, speaking into the microphone carefully band-aided there, its delicate lead snaking up his arm, embracing his shattered ribcage, plugging into the wafer-thin recording unit tucked into the inner pocket of his overalls.

At night, in his cot in the supply closet by the arcade, the cuticles of his toes still burning from the ammonia and bleach and creekwater of mopping, LP unwinds himself from the mic, jacks an earphone into the recorder, and transcribes his notes feverishly. That's how manifestos are written: with fever. Anything less would be trivial, not worth slogging through concessions and lane duty by day, guarding the place at night. Mary Boy offered him the security gig when he noticed LP had taken up residence at Fool's Hip. LP is pale from it, sunless; he hasn't stepped outside Fool's Hip for seven monthsãmoons, they're called now. It's all the same. Another part of his job is scraping graffiti off the bathroom stalls, both men's and women's.

On one of the stalls in the men's bathroom, like clockwork, there are always suggestions to LP, likely from Mary Boy, adopting some indirect managerial tactic or another. He copies them all into his manifesto. One of them was why don't you grow your hair like a real Indian? The time LP found that, he stayed up all night answering it in his notebook, then erased it all before morning, even recarved the question into the stall, to pretend he hadn't seen it. Maybe it wasn't for him. Maybe it wasn't even Mary Boy.