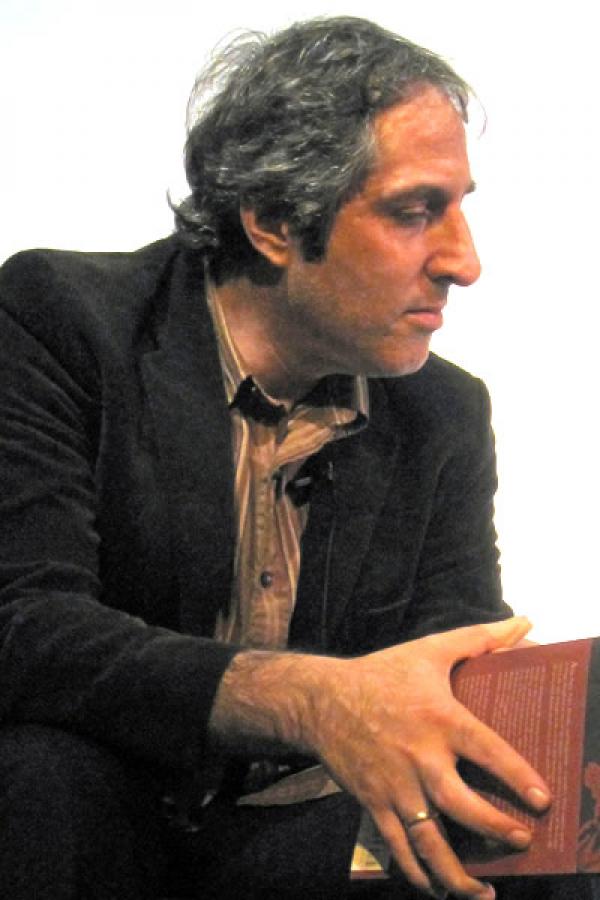

Alex Zucker

Photo by Jiri Zavadil

Bio

Alex Zucker's first visit to Czechoslovakia was in 1987. He was inspired to translate by Peter Kussi, his Czech instructor at Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs, where in 1990 he received a master's degree. From 1990 to 1995 he lived in Prague. City Sister Silver, his translation of Jáchym Topol's first novel, was selected for the guide 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. All This Belongs to Me, his translation of Petra Hůlová's first novel, received the National Translation Award from the American Literary Translators Association. He currently works for the Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation, a not-for-profit organization for genocide prevention.

Translator's Statement

Markéta Lazarová is an enormous challenge for the English‐speaking translator. Published in 1931, the novel was not only critically acclaimed but was also a bestseller. This despite a style that is a vigorous brew of archaisms drawn straight from the 16th‐century Bible of Kralice (the first full translation of the Bible into Czech), sprinkled with downright vulgarities, courtesy of the everyman plopped in the corner pub.

One source summarizes the novel as the story of a feudal lord's daughter who is kidnapped by neighboring robber knights and becomes the mistress of one of them. But the story line's not the whole story. In Markéta Lazarová Vančura does for Czech literature something akin to what James Joyce did for English-language literature with Ulysses: breaking with the realism that previously dominated to open up a new frontier in the realm of style. Unlike Joyce and other modernist novelists in English, however, Vančura sets his action not in the present but in medieval times, revolving around nobles whose lives of killing and robbery make a mockery of the coffeehouse intellectual Czechs of the day. "You have become truly too sensitive from musing upon our nation's nobility and fair manners," as the author-narrator states in the opening paragraph.

The only English translations of Vančura's writings are the now out‐of‐print The End of the Old Times (1965, trans. Edith Pargeter) and the recent Summer of Caprice (2006, trans. Mark Corner). Markéta Lazarová has been translated into Spanish, German, French, Polish, Russian, and Croatian, but never into English. F. X. Šalda said the feeling he had reading the book in 1931 was akin to catching a buzz. My aim, in translating it, is for readers today to feel the same.

An excerpt from Markéta Lazarová by Vladislav Vančura

[translated from Czech]

Folly scatters without rhyme or reason. Lend an ear to this tale of a place in the county of Mladá Boleslav, in the time of the disturbances, when the king strove for the safety of the highways, having cruel troubles with the nobles, who conducted themselves downright thievishly, and what is worse, who shed blood practically laughing out loud. You have become truly too sensitive from musing upon our nation's nobility and fair manners, and when you drink, you waste the cook's water, spilling it 'cross the table, but the men of whom I speak were an unruly and devilish lot. A rabble which I cannot compare to anything else than stallions. Precious little cared they of that which you account as important. Comb and soap! Why, they did not heed even the Lord's commandments.

'Tis said that there were countless such ruffians, but this story concerns itself with none save the family whose name most surely calls to mind Václav unjustly. Shifty nobles they were! The eldest amidst this bloody time was baptized with a graceful name, but forgot it and called himself Kozlík till the time of his beastly death.

The reason for this was most surely that baptism inspired in him no higher thoughts, but in part his method of clothing himself had also a share in the matter. The fellow was fixed all in furs, and because he was bald, he wore wrapped round his head a goatskin. In truth he had reason to take such care about his skull, for it had been split apart and healed only haphazardly.

'Tis more than certain that any military man in today's times would have passed away from the wound sooner than the medical corps had handed him a spoonful of tea, yet Kozlík! He slapped clay upon his head and rode home a horse whose flank had been bloodied by use of a barbarous spur. Pay him a remembrance less harsh for the fact that he was too brave to shriek in pain. Now then, Kozlík thus stigmatized had eight sons and nine daughters. Alas, he did not account this blessing as God's grace and boasted before those like him when in the seventy-first year of his age his youngest son was born. His wife, Lady Kateřina, had just fifty-four years at the christening.

What fertility! If the knife did not dry of blood for even a moment in those days, so many sources of life came the murderers' way that you are prone to envision them as angels of annunciation. See them stand even now at the head of the conjugal beds, like chubby waifs in tight clothing, face ruddied, foreheads jutting with veins.

Blood quick renews itself in Herculean times. Some of Kozlík's older sons were likewise blessed with children. Five dear daughters were already married off and four were as yet maidens. The old man scarce knew them, they were less than drudges.

* Bock

(Permission courtesy of Vladislav Vančura -- heirs c/o DILIA, 1931)

About Vladislav Vančura

Markéta Lazarová was a bestseller when it appeared in 1931. But it was not Vančura's first. The surgeon-turned-writer had five novels under his belt by then, including two bestsellers: Baker Jan Marhoul (1924) and Summer of Caprice (1925). He was also founding chairman of the Czech avant-garde art association Devětsil, a film director, a playwright, and from 1921 to 1929 a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

In 1939, after Hitler occupied the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia, Vančura, although no longer a Party member, joined an underground Communist resistance group. On May 12, 1942, the Gestapo arrested him and tortured him at their headquarters in Prague. On May 27, two members of the Czechoslovak army-in-exile, parachuted in from Britain and assassinated Reinhard Heydrich, the local Nazi ruler (Reichsprotektor). In retaliation, the Nazis executed more than 2,000 members of the Czech elite, including, on June 1, Vančura.

As a writer, Vančura was best known for his expressive amalgam of archaic speech and popular idioms. Three of his novels have been made into films, and the cinematic adaptation of Markéta Lazarová, by director František Vláčil in 1967, is viewed by many as the greatest Czech film of all time.