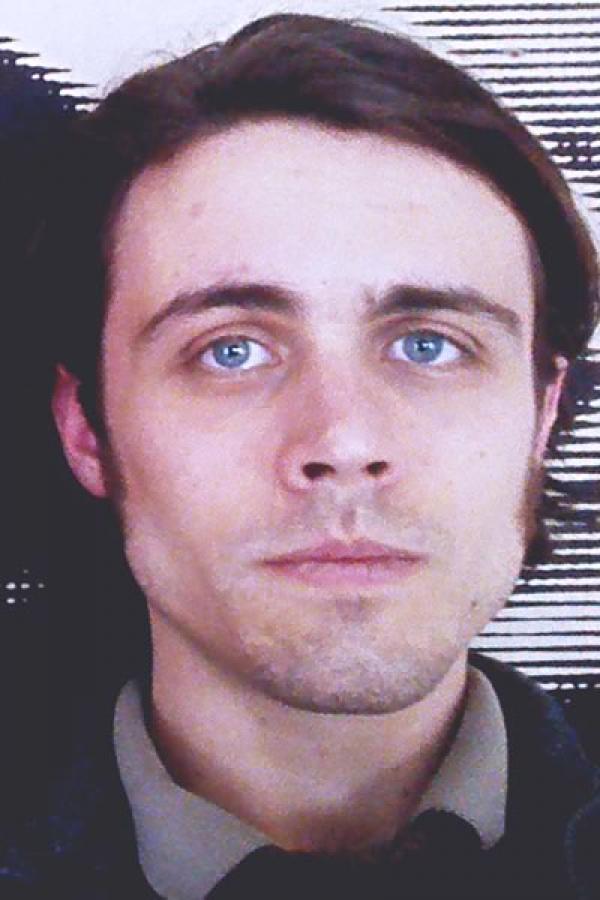

Kit Schluter

Photo courtesy of Kit Schluter

Bio

Kit Schluter is a poet and translator living in Oakland, California. Among his published translations from the French and Spanish are Jaime Saenz's The Cold (Poor Claudia), Marcel Schwob's The Book of Monelle (Wakefield Press), and Amandine Andre's Circle of Dogs (Solar Luxuriance, in collaboration with Jocelyn Spaar). Among his forthcoming translations are Anne Kawala's Screwball (Canarium Books), Marcel Schwob's The King in the Golden Mask (Wakefield), and Michel Surya's The Impasse (Solar Luxuriance). His personal writing can be found in Boston Review, BOMB, and Elective Affiities, among other publications. He co-edits O'clock Press, and curates the reading/performance series Wild Combination. Kit is the recipient of a Glascock Prize and a Boston Review/"Discovery" Prize, and holds an M.F.A. from Brown University.

Translator's Statement

When I sit down to begin translating a book, I like to imagine that I am sitting down to string an instrument I have never encountered before, an instrument with as many strings as the book I am translating has words. A book's translation is a slow task, and, like the tuning of an instrument, a deliberate one, one in which the pitch of every term needs be weighed very precisely against every other, and at times I admit it feels an impossible one. A book's translation is full days, full lived days, and it is weeks and months and years, and when it seems an impossible task, it feels also like an endless one, and at times a defeating, or even defeated, one. But when I think of what this fellowship affords me, I think of the time, and I think of the materials, that I have been given, and those which I myself will find, using those materials provided, to translate a book. And I am able to imagine an instrument with finer strings, an instrument with a more truly resonant body.

Throughout his work, Marcel Schwob forged myriad worlds, whose contours were culled from the realms of folklore, classical histories and occult texts, studies of Europe's lost languages, primary-source accounts of medieval thugs and their slang, the picaresque, the unabashedly fantastical. The result of this factual-fictional alchemy was a literature of such hallucinatory detail and linguistic specificity that the reader is left wondering whether the text she is encountering is absurdist fiction or obscure history. To read Schwob's fiction, then, is to encounter history in its most scintillating, ebullient form; to read his criticism is to observe a mind whose capacity for inventively leveraging factual details is unparalleled. The aims of my Selected Writings of Marcel Schwob will be to (re)introduce a more generous selection of Schwob's work to the English-reading community than is currently available, and to write a critical appendix that will give English-language readers perspective on Schwob's endurance, in France and abroad, from his own day to our contemporary moment.

M I M E X X by Marcel Schwob

χαρδια Akmé

[Translated from the French]

Akmé passed as I was still pressing her hand to my lips, and the mourners gathered around us. A chill sank to her lower limbs, and they grew pale and gelid. Then it rose to her heart, which ceased its beating, like a hemorrhaging bird you might find laid out, its talons clenched to its gut, on a morning of frost. Then the cold reached her mouth, which was something of a deep crimson.

And the mourners rubbed her skin with Syrian balms, and bound her feet and hands, the better to lay her upon the pyre. And the red fire lunged at her like a wretched lover on a summer night, to devour her with its blackening kisses.

And the funereal men, whose vocation this is, brought to my door two silver urns, wherein lie Akmé's ashes.

Adonis passed away thrice, and thrice the women lamented on the rooftops. And this third year, on the night of the festivals, I had a dream.

It seemed to me my dear Akmé had appeared by my bedside, clutching her chest with her left hand. She was come from the realm of shades: for her body was strangely transparent, save for the place of her heart, where she pressed her hand.

Then grief awoke me, and I lamented like the ladies who weep Adonis.

And sleep's bitter poppies made me drowsy again. And again it seemed to me my dear Akmé, by my bed, was pressing her hand over her heart.

Then I lamented again and begged the cruel guardian of dreams to retain her.

But she came a third time and gestured with her head.

And I do not know by which dark path she led me to the meadows of the dead, girdled by the aqueous belt of the Styx, where the black frogs shriek. And there, having sat herself down upon a hill, she withdrew the hand with which she had covered her breast.

Now Akmé's shade was clear as beryl, but I saw in her chest a red stain in the shape of a heart.

And without a word she pleaded with me to regain her heart of blood, so she might wander painlessly through the fields of poppy that wave like the wheat fields over the Sicilian country.

Then I took her in my arms, but felt naught save the subtle æther. And it seemed that blood was flooding into my heart; and Akmé's shade had vanished into total transparency.

Now have I written these lines, for my heart is swelled with the heart of Akmé.

About Marcel Schwob

Marcel Schwob (1867 – 1905) was a Jewish-French symbolist author, remembered for his abundant and various short stories, literary monographs, chronicles of fin-de-siècle Paris, and linguistic treatises on medieval slang, much of which sprang from his fabled devotion to archival research. While his work has fallen into relative obscurity in our time, it was revered in his day by writers as various as Colette, Rémy de Gourmont, Stéphane Mallarmé, Jules Renard, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Both Alfred Jarry and Paul Valery dedicated their first books, Ubu Roi and Introduction to the Method of Leonardo Da Vinci, to him. The deep personal influence of his writing has been noted and explored by a number of modern luminaries, including, but not limited to, Roberto Bolaño, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, and Fleur Jaeggy. Notably, he is the uncle of Lucy Schwob, better known today as the Surrealist author and artist Claude Cahun.