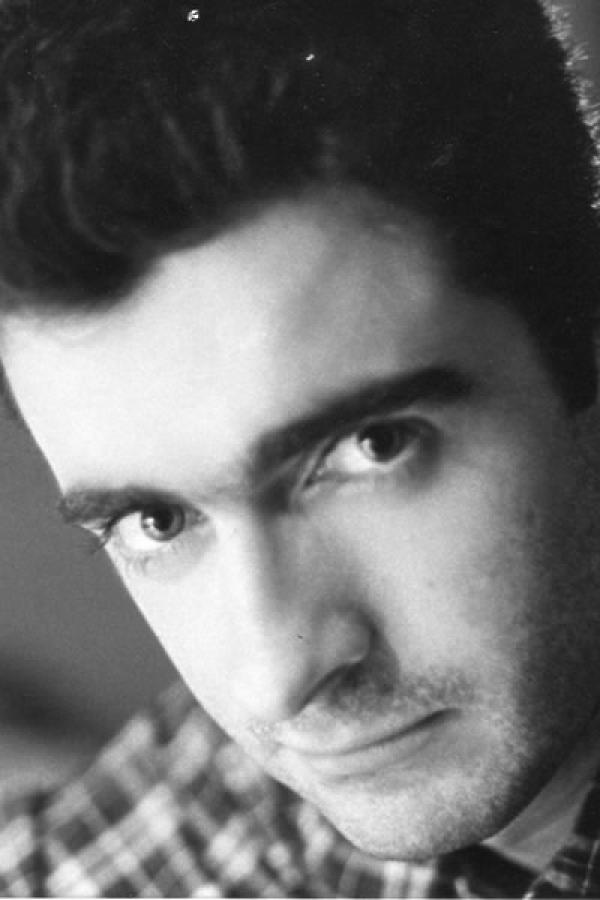

Pedro Enrique Rodriguez Jr.

Photo by Kazuo Nakajima

Bio

Pedro Rodríguez was born in Miami and grew up there on the banks of a broad canal, watching alligators and turtles and fish. Later, for the sake of books, he moved north, and studied literature and music at Bard College. Later still a Fulbright plucked him from his beloved New York City and dropped him in Paris, where he lives today with wife and child. He has scrubbed floors, unloaded trucks, bagged groceries, cooked short orders, waited tables, edited copy, taught English, written, and translated. He travels on foot by preference and runs for fun. He also plays music and indulges in the sciences, particularly physics and biology. He strives to achieve an intuitive grasp of mathematics one day and to teach his son how not to fool himself.

Translator's Statement

Every now and then a literary man blows me down (e.g., Robert Fitzgerald, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Murasaki Shikibu), but the older I get the more I admire adventurers: the late Patrick Leigh Fermor, for example, or Henry David Thoreau, or unfashionables like T.E. Lawrence and Richard F. Burton, or good old Charles Darwin, despite the warty prose.

Another favorite adventurer, Richard Feynman, put his finger on why, though it was the academy he aimed to squash: "The theoretical broadening which comes from having many humanities subjects on campus is offset by the general dopiness of the people who study these things." *

As a repentant dope, unfit to loosen Feynman's shoelace, I can't afford such derision, but my heart is with him. We humanists and writers like to pretend that we are plumbing universal depths. Let us languish, we warn, and the earth will come to a halt, civilization perish. Well, I figure the world could get on without us, without fellowships, without translation even. After all, the craft dates back a few thousand years in a past worth billions, and for most of its history has affected only a handful of people in any non-mercantile way. Perhaps marvels sparkle on the far side of another dark age, or in the pit of its nadir. Who knows?

Meanwhile I will do what I do for the only reason that makes sense to me: delight, the delight of a Cherry-Garrard nearing the pole, of a Burton striding out of Harar with his skin.

But how nice it is, how very nice, to get a reward for my pains! I am heartily grateful to the NEA's administrators and panelists, and especially to the taxpayers.

* Krauss, Lawrence M., Quantum Man: Richard Feynman's Life in Science, Atlas &Co., W.W. Norton & Company (New York, 2011), p. 165.

from Eaux et lumières (Water and Light) by George Groslier

[translated from French]

An ant, transparent like a drop of honey, advances along the handrail. Thorax angled up, goatish head aloft, she carries a cooked grain of rice in her mandibles and hurries along, as proud as can be. She is a red ant: the most ferocious beast in the land. Sensing the slightest danger, she will bite immediately, wherever she is, and cede no ground. She digs in her two sharp mandibles, rights her belly, braces herself with her legs, and pulls and pulls. If the elephant and panther were as courageous and aggressive, man would no longer walk the earth.

She is the scourge of travelers, and she is everywhere, the dirty little thing! At this season and in this flooded region the trees are covered with her like. Not long ago, when I was in northern Cambodia surveying the ruins of Banteay Chhmar, there were so many of these ants that I nearly gave up my investigations. They would slip into my clothes and feast on my skin. Oh yes, I would have given up had it not occurred to me to strip until I was nearly naked. With mine enemy thus exposed, I had a coolie dust me off with a broom of leaves.

But let us return to the ant on the handrail, this Amazon turned housemaid, who transports her grain of rice and aims to return to the tree whence she fell, though in fact she is now herself transported on this launch. I bar the way with a finger. She tries to go around. I advance. She flees to the left. The obstacle again. She rears up, vibrates -- things are taking a nasty turn! In her anger, she comes to believe that she is gripping my finger rather than the grain of rice. She squeezes her mandibles, and the grain, cut in two, falls to the sides.

If on this beast the Creator has bestowed a bit of vanity along with the courage, the fierceness, and the hardheadedness, imagine the vexation that must be welling up in that tiny brain! With two flicks I pitch the grain halves into the water. The ant turns about, seeks its goods, and departs. I leave her to her double humiliation.

(Permission courtesy of Nicole Groslier and recorded heirs of George Groslier)

About George Groslier

By virtue of his ideals, George Groslier (1887–1945) was in effect a gently anti-colonial French colonialist. Though highly visible in the Protectorate of Cambodia, Groslier devoted his life not to "civilizing" the Khmer but to understanding, restoring, and celebrating their craftsmanship. He founded their national museum and a school for the ancient arts, explored and surveyed their temples and pagodas, and teased out the significance of their ancient architecture, not by musing in a chair but by sweating for months in the jungle: measuring, cataloguing, comparing. He died under torture just two months before the Second World War's end.