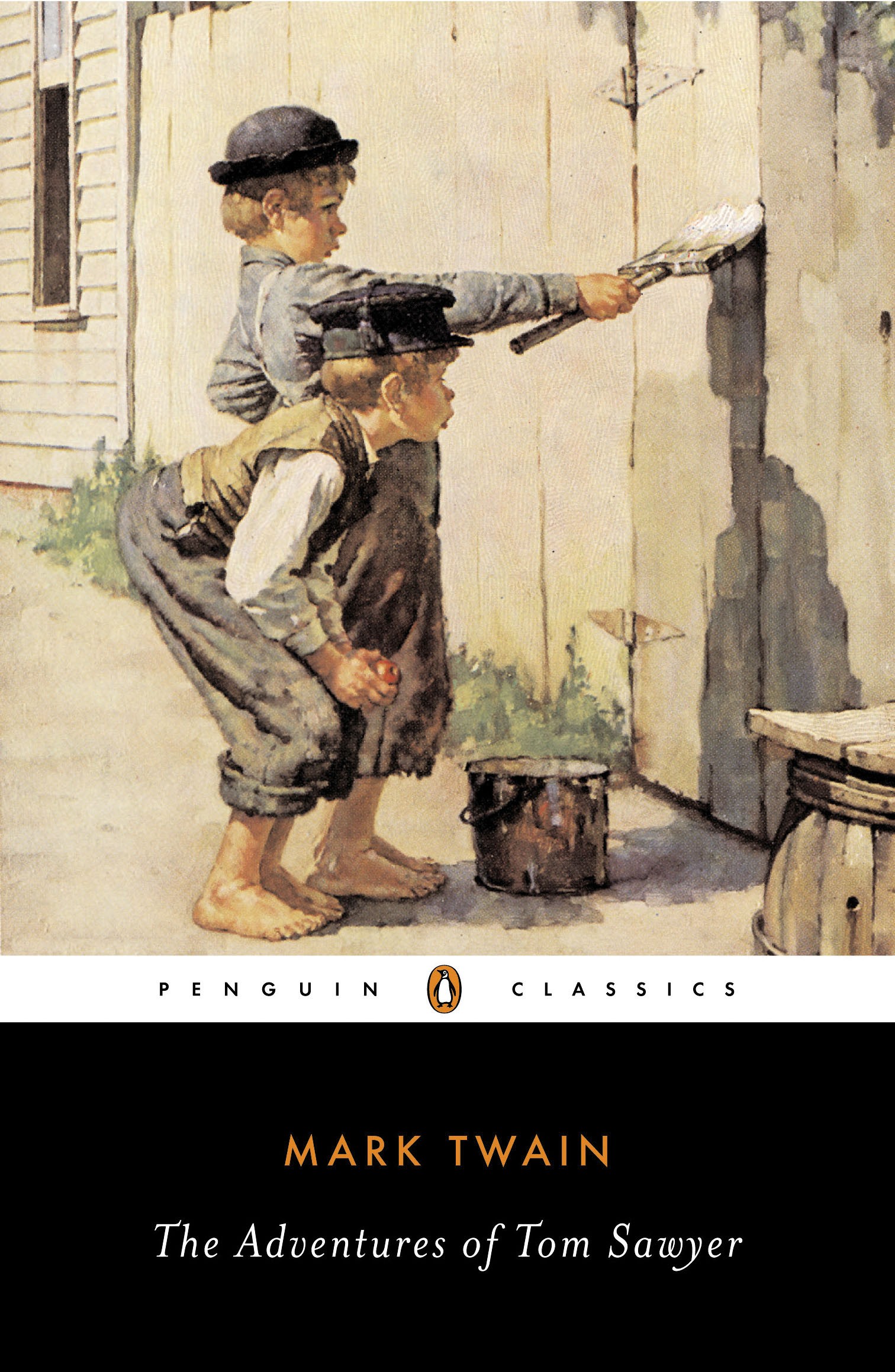

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Overview

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is not merely a literary classic. It is part of the American imagination. More than any other work in our culture, it established America's vision of childhood. Mark Twain created two fictional boys, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, who still seem more real than most of the people we know. In a still puritanical nation, Twain reminded adults that children were not angels, but fellow human beings, and perhaps all the more lovable for their imperfections and bad grooming. Neither American literature nor America has ever been the same.

"The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—it’s the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning." —from an 1888 letter

Overview

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is not merely a literary classic. It is part of the American imagination. More than any other work in our culture, it established America's vision of childhood. Mark Twain created two fictional boys, Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, who still seem more real than most of the people we know. In a still puritanical nation, Twain reminded adults that children were not angels, but fellow human beings, and perhaps all the more lovable for their imperfections and bad grooming. Neither American literature nor America has ever been the same.

Introduction to the Book

Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) is a book for readers of all ages. Most readers pick it up young and enjoy it, but too few come back to it later on, when its dark shadings and affectionate satire of small-town life might hit closer to home.

The book sold slowly at first but has since become the archetypal comic novel of American childhood. It begins with several chapters of scene-setting episodic skylarking by Tom and his gang. All the grown-ups in the book fret about Tom, fussing at him about his clothes and his manners, but also about his future, and whether this orphaned boy can ever grow up right.

Meanwhile, Tom just wants to cut school, flirt with the new girl, get rich, and read what he pleases. Only after he and his wayward friend Huckleberry Finn accidentally witness a murder will he at last get the chance to live out an adventure as heroic as any in his storybooks. When Tom and his beloved Becky Thatcher become trapped in a dark cave, he must call on all his imagination and ingenuity if he wants even a chance at growing up.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer has likely suffered over the years from unfair comparisons to its famous sequel. Huck gets fuller development in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), where he escapes down the river with the runaway slave Jim and, in spite of himself, begins to discover his conscience. But just because Huckleberry Finn is the deeper book doesn't make Tom Sawyer mere kids' stuff. Twain never could make up his mind whether Tom Sawyer was for kids or grown-ups, and his book is the better for it.

If Tom stepped out of his 19th-century Missouri small town and into a contemporary American classroom, a guidance counselor would probably tag him as an at-risk latchkey kid. Reading Tom Sawyer today is an invitation to talk about how American childhood has and hasn't changed—and also to laugh at Twain's enduring invention of a great American comic voice.

"Now the raft was passing before the distant town. Two or three glimmering lights showed where it lay, peacefully sleeping, beyond the vague vast sweep of star-gemmed water."

—from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Major Characters in the Book

The Kids

Tom Sawyer is a smart, imaginative, conniving, bossy boy growing up in fictional St. Petersburg, Missouri. He's usually in trouble by the time he gets out of bed, but he's too well-meaning and funny for anybody to stay mad at him for long.

Huckleberry Finn is the son of the local drunk. Huck does most everything that Tom puts him up to, while Tom covets Huck's freedom and independence.

Becky Thatcher is the new girl in town, and Tom falls hard for her. She's flirty and headstrong, sometimes manipulative, but brave enough with Tom by her side.

Sid Sawyer, Tom's half-brother, is the most disgusting goody two-shoes on two legs. Aunt Polly is always measuring Tom against him even though he's a shameless tattletale, a worrywart, and a crybaby.

The Adults

Aunt Polly has taken care of Tom since his mother died. She truly loves him, but he's a handful, and she wishes he could be more like that nice Sid.

The Widow Douglas takes Huck into her home and tries to reform him. Her rigidly scheduled life rubs him the wrong way, and only Tom has any luck talking him into staying.

Muff Potter is a drunkard. He's not an evil man exactly but weak, cowardly, and ripe for anyone to come along and take advantage of him.

Injun Joe embodies all the fear of the unknown that a small town might feel on the edge of a great unsettled wilderness. Violent and cruel, he earns a little of the reader's sympathy only at the very end.

"He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it—namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain."

—Mark Twain, from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain's two most enduring books, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and its often underrated junior partner The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, represent two sides of the same raft. Tom Sawyer is sunny and upright, skirting whirlpools but ultimately hugging the shore of convention. Huck Finn is its deep, dark, wet, rushing underside. Nowhere do these flipsides of Twain's productively riven personality bob up more conspicuously than at two moments common to each novel: when both title characters attend their own funerals, and when each novel ends with a shaky vow of reform.

In both books the hero gets to live out perhaps every morbid, underappreciated kid's greatest fantasy: to spy on his own mourners and hear how sorry everybody is, and then to come back from the dead to a hero's welcome. "She would be sorry some day," Tom says of Becky, "maybe when it was too late. Ah, if he could only die temporarily!" Typically, Tom lucks into his version of this fantasy. Huck, on the other hand, deliberately fakes his own death to escape his father.

The books' endings, too, are strikingly similar. In Tom Sawyer, Huck reluctantly allows the Widow Douglas to take him in, but on the last page he doesn't sound terribly optimistic about sticking it out with her. Meanwhile, in the famous ending to Huck Finn, the title character vows to "light out for the territory" if the widow tries too zealously to "sivilize" him, because he's "been there before." Huck has indeed been there before, because Tom Sawyer ended on this same skeptical note.

In fact, Tom and Huck fit their namesake books perfectly. Like Tom, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is outrageous, but also smooth, artful, and anxious to please. A model of literary construction, it stands up straight. Like Huck, on the other hand, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn slouches. It's ungainly, in need of finishing, and its language often lands it in trouble. It's also touched by genius. There's no denying that something's fundamentally haywire with the end of Huck Finn—yet look closer and see if it isn't a flaw common to every imperfect life. Huck and Jim have gone wrong after the fork, they've overshot something crucial, they've lost their way and don't know how to get back. Who among us hasn't felt the same? Twain certainly should have. He published his best book at 50 but lived to nearly 75.

Seen this way, Tom and Huck's Mississippi River becomes an endlessly renewable metaphor. Twain saw as clearly as anybody that as Americans we're all on this raft together, afloat between oceans, crewed by oarsmen of more than one color, tippy but not aground, not yet.

- How do you think American childhood has and hasn't changed since the 1840s?

- The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was already a historical novel when it was written, fully 30 years after it is set. Does it feel realistic or nostalgic?

- Between Tom and Huck, who's more of an outlaw and who's a conformist?

- Who emerges with more dimension in the book, African Americans or Native Americans? Can you detect any hints of Twain's late-career humanism?

- How might the fence in Aunt Polly's yard serve as a symbol? What might be implied by Tom getting others to "whitewash" the fence for him?

- How old are Tom and his classmates? Do they behave convincingly for their age?

- Why do you think Twain made Tom an orphan?

- Which do you enjoy more, Twain's dialogue or his descriptions? How does one complement the other?

- If you could eavesdrop on your own funeral, what do you think you would hear?

- Find a sentence that makes you laugh out loud. Change one word. Is it as funny? If not, why not? If so, change one word at a time until the joke weakens or dies. What made it work before?

- What important roles did Huck and Becky play in Tom's success, even though Tom is celebrated as the town's hero?

- Tom makes a difficult decision when he tells the truth about the murder. Compare the way he comes to his decision with Huck's choice to help Jim in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. How does Tom's motivation differ from Huck's?

- Some readers believe that Tom develops a conscience by the end of the novel. Do you agree? Is there evidence to suggest that Tom has changed?