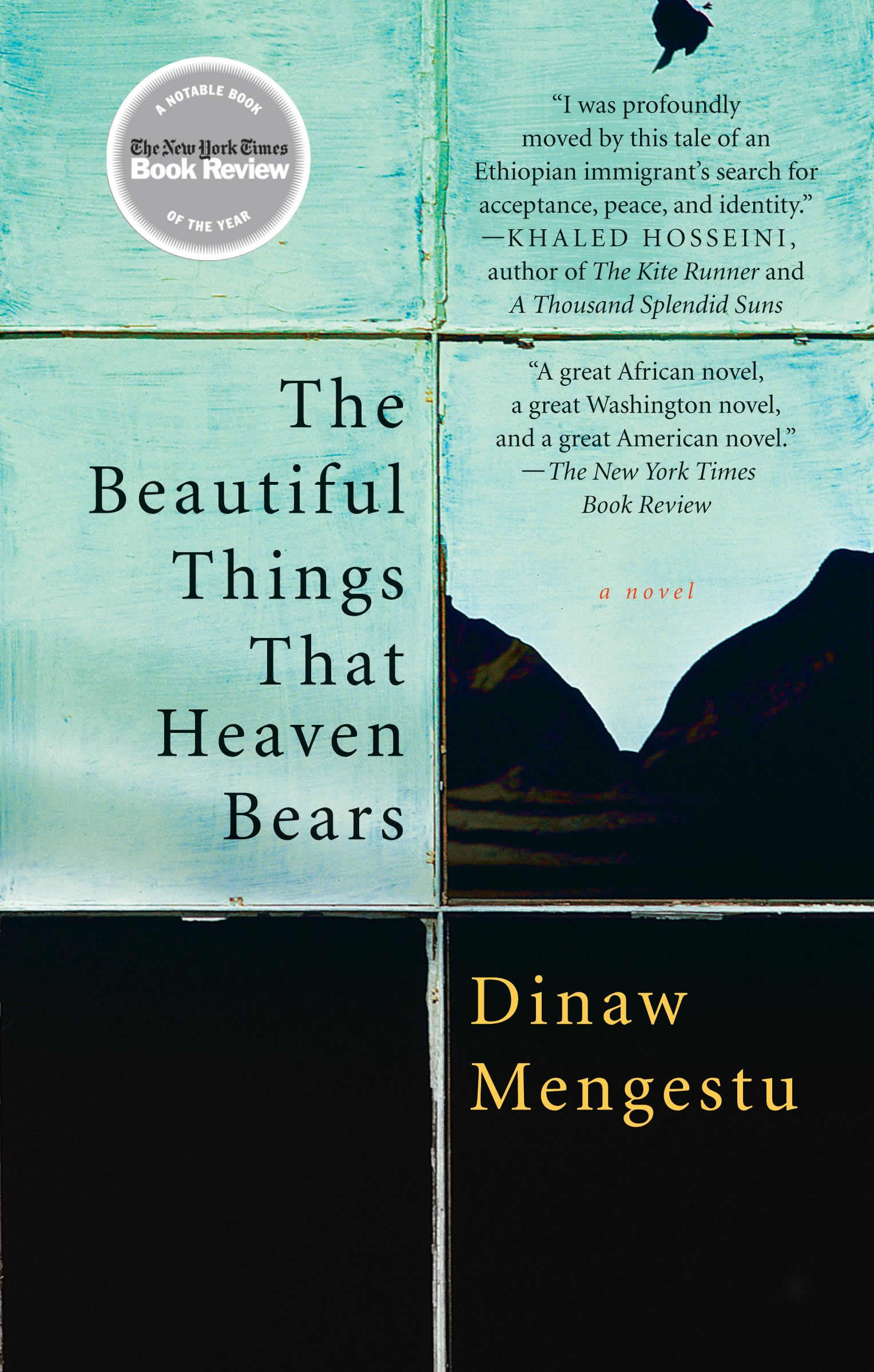

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

Overview

Like the protagonist of this 2007 debut novel, MacArthur Foundation Fellow Dinaw Mengestu came to the United States from Ethiopia, fleeing with his family after the Communist Revolution in 1974, which took the life of his uncle. Called “a great African novel, a great Washington novel and a great American novel” (The New York Times Book Review), The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears alternates between the present and the past to tell the story of a lonely Ethiopian shopkeeper in a D.C. neighborhood undergoing gentrification. “Almost every page reminds us that ‘departure’ and ‘arrival’ are deceptively decisive words” (The New York Times). Mengestu “belongs to that special group of American voices produced by global upheavals and international, if sometimes forced, migrations,” writes the Los Angeles Times. His “assured prose and haunting set pieces … are heartrending and indelible” (Publishers Weekly).

"The stories he invented himself he told with particular delight. They all began in the same way, with the same lighthearted tone, with a small wave of the hand, as if the world were being brushed to the side…" —from The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

Overview

Like the protagonist of this 2007 debut novel, MacArthur Foundation Fellow Dinaw Mengestu came to the United States from Ethiopia, fleeing with his family after the Communist Revolution in 1974, which took the life of his uncle. Called “a great African novel, a great Washington novel and a great American novel” (The New York Times Book Review), The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears alternates between the present and the past to tell the story of a lonely Ethiopian shopkeeper in a D.C. neighborhood undergoing gentrification. “Almost every page reminds us that ‘departure’ and ‘arrival’ are deceptively decisive words” (The New York Times). Mengestu “belongs to that special group of American voices produced by global upheavals and international, if sometimes forced, migrations,” writes the Los Angeles Times. His “assured prose and haunting set pieces … are heartrending and indelible” (Publishers Weekly).

Introduction to the Novel

"After seventeen years here, I am certain of at least one thing: the liberal idea of America is at its best in advertising." — Sepha Stephanos in The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

In this novel, Dinaw Mengestu describes the pain of exile, when one is violently uprooted from his or her homeland. Having fled the Ethiopian Red Terror of the late 1970s to live and work in Washington, DC, Sepha Stephanos is acutely aware of the loneliness, sadness, and dislocation that accompany his pursuit to find a quiet refuge from the ghosts of his old life. Seventeen years have passed since Stephanos immigrated to Washington, where he began working as a hotel valet and met his two companions, also African immigrants, “Joe from the Congo” and “Ken the Kenyan.”

Dinaw Mengestu and his sister, Bezawit (Courtesy of the Mengestu family)

Dinaw Mengestu and his sister, Bezawit (Courtesy of the Mengestu family)Meeting weekly in Stephanos's neighborhood grocery to reminisce about their pasts, they play a bitterly absurd game matching African dictators with countries and coups. Their friendship is a way to navigate living in between two worlds: the Africa they left behind in the midst of war, and the America they never feel at home in. Stephanos meets Judith, an American history professor, and her biracial daughter Naomi, when they move in next door. As Judith renovates the four-story brick mansion, Stephanos builds a friendship with Naomi, who visits his failing shop and transforms the quiet, somber space to a haven of imaginative storytelling and reading Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov aloud. However, as Judith becomes part of the gentrification process that displaces longtime residents of DC's decaying Logan Circle, tensions arise, and Stephanos's relationships with both Judith and Naomi become precarious.

"What was it my father used to say? A bird stuck between two branches gets bitten on both wings. I would like to add my own saying to the list now, Father: a man stuck between two worlds lives and dies alone. I have dangled and been suspended long enough.”

—Sepha Stephanos in The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

Alternating from past to present, the novel poses questions not only about the immigrant experience in America and the fraught nature of attaining the American dream, but also about the complex nature of various displacements: from one's country, one's past, one's prior ambitions, and one's lost loves.

Major Characters in the Novel

Sepha Stephanos

After he watches his father beaten and kidnapped by soldiers, Stephanos flees Ethiopia to the United States. He opens a shabby local grocery in Logan Circle and lives a very quiet and lonely life, haunted by his past.

Kenneth

“Ken the Kenyan” is a smartly dressed engineer and one of Stephanos's two close friends. He encourages Stephanos to be ambitious in his new country.

“A man, I told myself, is defined not by his possessions but by the company he keeps. That was a phrase I had stolen from my father, along with this: the character of a man is like the tail of a monkey; it is always behind him.”

—Sepha Stephanos in The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

Joseph

“Joe from the Congo” is a waiter at an expensive restaurant, aptly called The Colonial Grill. His real passion is studying literature. Even though he relinquished his dream of getting his PhD, he's kept all his college books and quotes poetry to illustrate a point.

Judith

A professor of nineteenth century American history, recently separated from her husband, she moves to Logan Circle with her daughter Naomi. Intent on creating a home for Naomi, Judith meticulously restores a four-story brick mansion while finding comfort and companionship with Stephanos.

Naomi

"Stubbornly independent," and taking pride in being able to chastise the world's shortcomings, Judith's eleven-year-old biracial daughter develops a special friendship with Stephanos.

Mrs. Davis

An elderly African-American woman, she is a longtime resident of Logan Circle and is Stephanos's neighbor. She represents the sizeable community concerned about recent evictions due to rapid gentrification.

Uncle Berhane

Stephanos's "uncle" is a family friend and the only connection Stephanos has to his family back home. He too fled Ethiopia, leaving behind a more prosperous life, and now lives in a small apartment in a densely populated Ethiopian enclave in suburban DC.

- How does Stephanos characterize his store? Does the store represent the American dream to Stephanos? Does he believe the American dream is attainable for him?

- Mengestu has said that Stephanos, Joseph, and Kenneth “love and mourn” their countries and the African continent as a whole. How did they employ the African dictators game to this end? How does the game and their discussions become a way to reconcile their bitterness and longing?

- Discuss the significance of Uncle Berhane's letters to U.S. presidents regarding the conflict in Ethiopia. What do they reveal about his character and how he locates himself as an immigrant in the U.S.?

- Examine the role of beauty and beautiful things in this novel. How does Mengestu cast our eye, or ask us to reexamine what we consider “beautiful?”

- Stephanos's trauma—watching his father captured and taken by a group of boy soldiers—is one of the most haunting moments in the novel. How does Stephanos remember his father? What do you make of Stephanos's final words to his father at the end of the novel?

- How do different immigrants in this story navigate the American dream? For example, Uncle Berhane, Joseph, and Stephanos have seemingly different orientations to their new home. How would you characterize each man's attitude about making a new life in the United States?

- The prose in this novel is unsentimental and sparse. How does the language contribute to the overall tone in the narrative? How does it provide insight into the characters' consciousness and internal experiences?

A Community’s Cultural Diversity is Brought to the Forefront With The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears in Indianapolis, Indiana

"The impact of the Big Read was a growing awareness of the cultural diversity of Indianapolis. Many program attendees were unaware that Indianapolis had an Ethiopian/Eritrean community and reported on evaluations that they were glad to learn of this community.

“The Big Read also challenged readers to think about their life experiences in categories beyond those of a specific immigrant group. Mr. Mengestu in his author talk spoke eloquently about how he hoped his book was not an ‘African book’ or an ‘immigrant book’ but a ‘human book’ about grief and loss and the American dream. Those in attendance at his lecture were from all ages and races and included members of the Ethiopian community.

"The Big Read also helped develop an ongoing understanding in the community of The Indianapolis Public Library (IndyPL) as a place for cultural exploration and exposure. While IndyPL has long participated in cultural programming, this has become a significant focus in the past three years. Over the past few years, IndyPL has highlighted the culture of our sister cities (Hangzhou, China; Campinas, Brazil; and Cologne, Germany.) The Big Read provided another platform for IndyPL to highlight a culture impacting the city and provide a safe, neutral space for program participants to understand the similarities and differences of multiple cultures.

"On program evaluations, attendees were highly complementary of the program and appreciated how the suite of programs helped deepen their understanding of a new culture and provided information they did not know. One book discussion participant said, ‘It was all new info. I knew nothing about Ethiopian culture.’ Many attendees at the talk with Mr. Mengestu enjoyed how his lecture provided more insight. ‘Hearing from the author himself adds to the understanding of the novel,’ another participant said on an evaluation."

Check out IndyPL’s opening event in this video:

– from a report by the Indianapolis Public Library (IndyPL), an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2014-15.

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears Inspires Compassion in a New York City Community

"The Big Read brought together people who might otherwise never have talked to each other and engaged them in profound discussions not only about Dinaw Mengestu’s beautiful novel and its characters and themes, but also about their own personal experiences of loss, alienation and joy, why they read, and what community means to them. Thus, it created bonds where none existed before. It also raised awareness about people in our community who are in some ways invisible – the immigrant shopkeepers whom we encounter daily while buying coffee, and others among us who are not on the path to the American dream. In this way, we believe it inspired compassion. It helped readers to look through the lens of a ‘have not’ at the changes taking place in our area, where gentrification threatens to turn us into a community of the wealthy and the poor. We hope the result will be more people seeking ways to redress this imbalance. Finally, the Big Read got people reading. Many people said that they didn’t often read, but were motivated to do so by the Big Read."

– from a report by the Goddard Riverside Community Center, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2014-15.

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears Engages Community with the Topic of Displacement in Buffalo, New York

"The choice of The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears was particularly appropriate to Buffalo at this moment, with its growing refugee population, including many who have come from Ethiopia. Issues central to this book, including the depiction of displacement and the tensions of gentrification, resonate strongly here. The project could not have occurred at a more relevant time, with issues of immigration at the forefront of local and national conversation, and literature offering a unique point of entry, and way to engage the community in these issues."

– from a report by the Just Buffalo Literary Center, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2015-16.

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears Ignites a Discussion on Gentrification in New York City

|

– from a report by the Goddard Riverside Community Center, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2014-15.

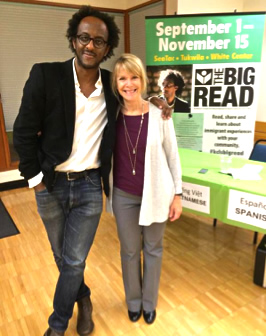

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears’ Impact Reaches from Washington State to Washington, D.C.

“In the areas of SeaTac, Tukwila and White Center there are socioeconomic divisions, particularly between those that are foreign-born new arrivals and those that are long-time residents. This plays out in the local politics as well as casual conversations. The selection provided an opportunity to address the ‘elephant in the room’ in a safe space. Folks could ask questions and share stores related to language barriers, cultural differences, changes in the neighborhood, etc. in relation to Mengestu’s novel.”

“Members of the Big read planning team also serve on the White Center Promise Network for Integrating New Americans (NINA), one of five networks nationwide selected to receive technical assistance from World Education, Inc. This team presented NINA activities, including participation in the Big Read, to the White House Domestic Policy Council at a briefing on October 29 in Washington D.C. The audience included the Special Assistant to the President for immigration Policy; the Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education; the U.S. Department of Education, among others. The following day, the team presented to fellow networks from Lancaster, PA; Boise, ID; Metropolitan Providence, RI and Fresno, CA as well as professional mentors from California to New York. Some network members expressed interest in bringing the Big Read to their community.”

|

![]()

|

– from a report by the King County Library System Foundation, an NEA Big Read grant recipient in FY 2015-16.

Mengestu family photo (Courtesy of the Mengestu family)

Mengestu family photo (Courtesy of the Mengestu family)