The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir

Overview

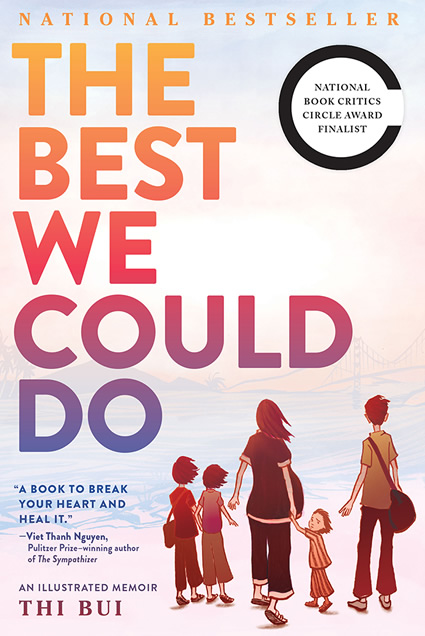

Before she began to work on The Best We Could Do in 2005, Thi Bui had never drawn a comic in her life. Twelve years later, the debut graphic memoir would be released to widespread acclaim from critics and literary heavyweights alike. An American Book Award winner, a National Book Critics Circle finalist in autobiography, and an Eisner Award finalist in reality-based comics, Bui’s memoir traces her family’s daring escape after the fall of South Việt Nam in the 1970s and their effort to build new lives for themselves in America. Bui documents parental sacrifice, excavates family histories, and grapples with the inherited struggles of displacement and diaspora. “This memoir feels not just created but also deeply lived” (The Washington Post). “A stunning work of reconstructed family and world history” (Booklist Online). “Narratively intricate, intellectually fastidious, and visually stunning” (Vulture). Writes Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize winner and board member: “A book to break your heart and heal it.”

"I began to record our family history...thinking that if I bridged the gap between the past and the present, I could fill the void between my parents and me." —The Best We Could Do

Before it would become a bestseller, before it had a title, before the first comic was drawn, Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do was a project of reconstruction: an attempt to bring together generations of family stories. “I was a graduate student and took a detour from my art education training to get lost in the world of oral history,” writes Bui in the book’s preface. "I was trying to understand the forces that caused my family, in the late seventies, to flee one country and start over in another.”

Dissatisfied with the limits of oral history, Bui turned towards other genres—hunting for a way to weave the personal, political, and historical. “I was inspired by some of the big graphic memoirs like Maus by Art Spiegelman and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi,” shared Bui with The Mary Sue. “And then, I didn't really want to write a memoir; [but] the oral history needed a protagonist to lead you through the story and I had to volunteer myself.”

The memoir opens with the birth of Bui’s son, an event that shifts the project from a historical reconstruction to a book about parents and children. Life with her new child, rife with potential and uncertainty, catalyzes a realization that family was “now something I have created—and not just something I was born into.” Thus, Bui returns to her parents’ histories: this time not just as their child, but as a parent herself.

The Best We Could Do slips seamlessly between perspectives, voices, and even decades. Bui and her mother, Hằng sit at a kitchen table in Berkeley, California, as Hằng recounts her past in Việt Nam. A moment later, there she is: a little girl diving deep beneath the waves in the coastal town of Nha Trang; surrounded by friends on the lawn of a French lycée; a bright-eyed, ambitious college student meeting Bui’s father, Nam, for the first time.

It takes longer for Bui to find the right questions for her father; but when she does, Nam’s stories come quickly, each of them with “a different shape but the same ending.” Born in 1940, as the world was “plunging headlong into chaos,” Nam grew up in the path of war and famine. Left with his grandparents in Lợi Đông after his father joined the Việt Minh, Nam remains haunted by the violence he witnessed as a child when the village was taken over by French forces during the First Indochina War. Decades later, in an apartment in San Diego, Bui remembers growing up with the terrified boy who would become her father. “Afraid of my father, craving safety and comfort,” she writes, “I had no idea that the terror I felt was only the long shadow of his own.”

This becomes a theme throughout the memoir: history as a shadow and memory as a cycle. “Rewind, Reverse,” reads one chapter title. “Either, Or,” reads another. “Fire and Ash,” “Ebb and Flow.” Bui’s move to New York City after college finds symmetry in Nam’s arrival as a young bachelor in Sài Gòn, reading Jean-Paul Sartre and Simon de Beauvoir with freedom on his mind. The birth of Bui’s son is a reminder of Hằng—“How did you do this SIX times?”—whose own labors become stories later on in the book. As Bui traces her family’s escape after the fall of South Việt Nam in 1975, she intersperses her own memories among her parents’, describing the chocolate bar her mother used to distract her and her sisters while Hằng provided translation help at the airport, her glee at seeing snow for the first time at her aunt’s home in Indiana, the two kinds of spaghetti her sisters would make when they came home from college to babysit.

“I keep looking toward the past, tracing our journey in reverse,” writes Bui. “Over the ocean, through the war, seeking an origin story that will set everything right.” Throughout the book, stories are constantly written and rewritten, told by one person and untold by another, “...with no beginning or end—anecdotes without shape, wounds beneath wounds.” With sweeping scale and careful intimacy, Bui mediates memory across generations. In her deft hands, a mother’s love is rendered in a piece of blood sausage. A chessboard becomes a neighborhood; chess pieces become a war. An unassuming brown file folder holds a lifetime’s inheritance.

“What becomes of us after we die?” Bui wonders in the last moments of The Best We Could Do. “Do we live on in what we leave to our children?” It is a question etched into every page of her memoir: what it means to be both parent and child, to translate memory into history, to search for a better future while longing for a simpler past. The book offers no clear answers, only a tribute to complexity: memory and grief, guilt and gratitude, love and sacrifice in all their equal parts. "She does not spare her loved ones criticism or linger needlessly on their flaws,” writes Publishers Weekly. “Likewise she refuses to flatten the twists and turns of their histories into neat, linear narratives. She embraces the whole of it.”

- In the preface to the book, Bui notes that The Best We Could Do originally began as a project of transcribing her family's “oral histories.” What is lost and what is gained by transforming an oral history into a written one? If you were to begin a record of your own family’s histories, how might you choose to begin?

- The title of the book first appears in the narrative on p. 55, a page titled “Hôpital Grall, September 1965.” What is the impact of its placement there? Does this context change your reading of the title? How does the phrase resonate with new or different meanings throughout the book? Who do you think is included in the “We”?

- Bui uses a variety of visual techniques throughout the book to emphasize dialogue, to switch perspectives, to move from place to place or to convey a sense of emotion. Can you think of a page in the book that you found particularly compelling? Why did this page appeal to you? What visual elements stand out? How do they shape your understanding of what’s happening?

- Throughout the book, time moves fluidly between past and present, often changing in the space between panels or pages. Choose a page in the book and consider the composition of the page. How much time is passing between panels? Does that passage of time stay constant across the page? What might change about this page if it was told as an oral history? As a written one?

- The Best We Could Do spans several decades and three generations. How does Bui convey the passing of time? How does she convey memory? How does she identify speakers or storytellers?

- In an interview with The Mary Sue, Bui spoke about her choices of color in the book. “I tried out blue, but I felt like there’s a certain kind of blue that just reads as graphic novel blue. Also, it didn’t work with the way the story felt with me so I tried a few different shades of brown and I finally found just the right shade.” What did you think of Bui’s choice of brown? How do you think it affected your reading experience? Did you notice anything about the ways Bui used color or shading to evoke a scene? Can you think of any colors in your own life that evoke clear associations or emotions?

- When visiting her family's old apartment in Sài Gòn as an adult, the author finds herself “documenting in lieu of remembering” (p. 180). What do you think is the difference between “documenting” and “remembering”? Which do you think the book is doing?

- Throughout the book, language plays a major role: whether the colonial French language taught to Bui’s parents in school, the Vietnamese language of her birth, the Malay language spoken at the refugee camp in Pulau Besar, or the English language in which the book is primarily written. In what ways does this multilingualism affect your experience as a reader? Why do you think Bui chose to translate certain moments in the text to English, while leaving others untranslated? How would you describe your own relationship to the language or languages that you speak?

- Bui presents the births of the six siblings in reverse chronological order (p. 42, 46, 47, 48, 50, and 52). Why do you think she did this? As a storytelling technique, do you think it was effective?

- The Best We Could Do opens with a timeline of the history of Việt Nam, focusing on the period of war from 1945 to 1975. Why do you think the author chose to preface the book with a timeline? Are there any dates on the timeline that are referenced in the book? Can you point to those moments?

- Birth and pregnancy play a prominent role throughout the book, which begins and ends with the birth of Bui’s son. "It was important for me to bookend this story with a very typical experience, a pretty universal and archetypal entryway,” Bui shared in an interview with Brooklyn Magazine. “Physical experiences have always been humbling experiences because they put you back in your body and help you connect with other people.”Did you find the opening scenes to be effective in this way? Can you point to any other moments of the book where physical experiences are used to “put you back in your body,” or to ground the reader? Were they effective?

- Over the course of the book, there is only one moment when Bui incorporates real photos (of her family at a UN refugee camp in Malaysia, p. 267). Why do you think she chose to use real photos here? After spending the greater part of the book without the incorporation of photos or found documents, what is their effect?

- At the end of the book, Bui writes: “But when I look at my son, now ten years old, I don’t see war and loss...or even Travis and me. I see a new life, bound with mine, quite by coincidence, and I think maybe he can be free” (328-329). How does Bui’s relationship with her son change over the course of the book? What about her relationship with her parents? How does her understanding of parenthood change? Her understanding of childhood?