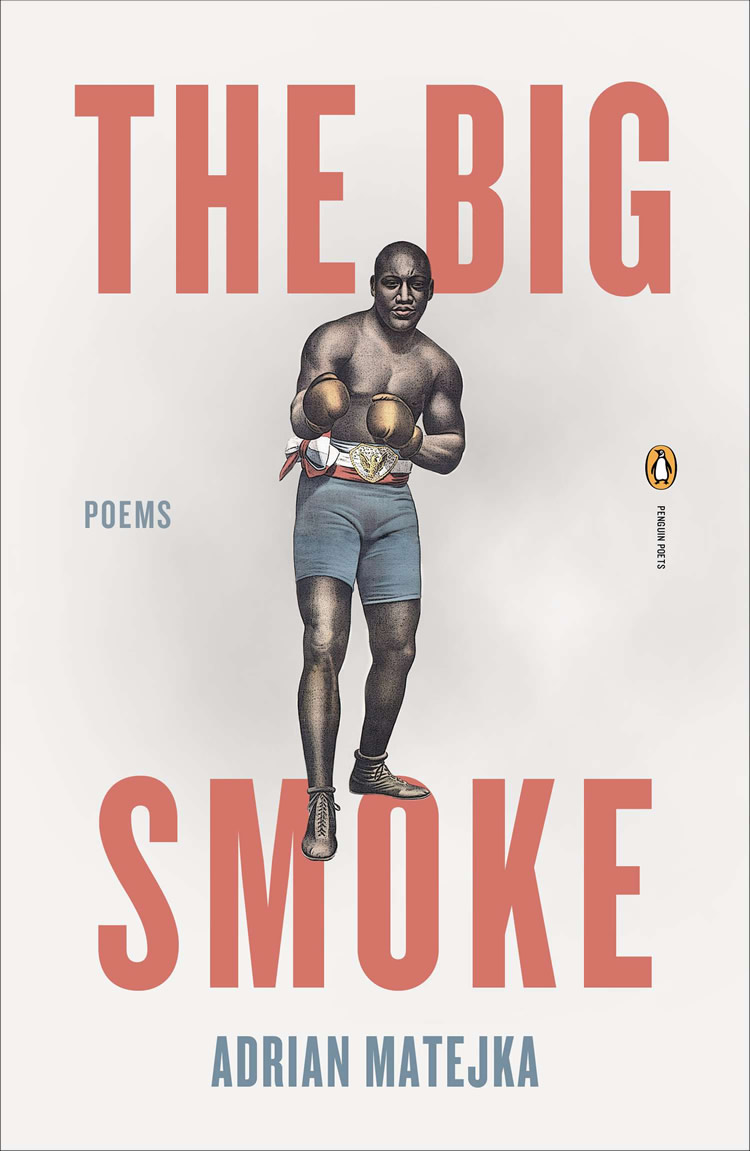

The Big Smoke

Overview

This title will no longer be available for programming after the 2020-21 grant year.

Legendary prizefighter Jack Johnson—the first African American to claim the title of world heavyweight champion—“comes so boldly to life” in The Big Smoke “one almost wants to duck” (Boston Globe). This third collection of poetry by award-winning poet and Indiana University professor Adrian Matejka has “the lean, long jab and agile step of a boxer” (National Book Foundation). Winner of the Anisfield-Wolf Prize and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, The Big Smoke explores the fighter’s journey from poverty to one of the most coveted titles in sports through the voices of Johnson and the women who knew him best. It’s a “rich, sometimes disturbing portrait of a fascinating, flawed, and complex man” (Washington Post) who “is troubled by his own demons but determined to win the ‘fight of the century’” (National Book Foundation).

"When I clinch a man,

it's like being swaddled in forgiveness."

— from The Big Smoke

Introduction

“When two boxers of even skill are in the ring together, the contest is as much about movement as it is [about] landing punches…the action that leads to or follows the punches is where the poetry lives…”—Adrian Matejka in the Cleveland Plain Dealer

It took Adrian Matejka two years of research before he was ready to write the first poem for The Big Smoke, a book that gives voice to the life and legacy of the boxer Jack Johnson. Johnson was born to ex-slaves during the Jim Crow era and became one of the most famous people in the world when he claimed the title of world heavyweight champion in 1908—the first African American to do so. To Matejka, the epic story of Johnson’s rise and fall naturally lent itself to poetry. “He managed to win the most coveted title in sports,” said Matejka, “but through the combination of his own hubris and the institutionalized racism of the time, he lost everything” (National Book Foundation).

The majority of the poems in the book are “persona” poems: poetic monologues written in Johnson’s voice. “What drew me to Jack Johnson…was his inability to speak for himself historically,” Matejka said. The “post-Reconstruction institutions—the newspapers and other media in particular—were in opposition to his success and did what they could to subvert him” (Barely South Review), all while they shaped his public image. Matejka also includes poems in the voices of three of Johnson’s lovers. “There was a story [Johnson] used to tell,” Matejka said, “about beating up a 25-foot shark while he was diving for shells. When he was 12. With his bare hands. The kind of fabulist who would add shark-fighting to his mythology is not the kind of person who is going to present himself in any self-aware or emotionally vulnerable way. So that’s where the other voices in the book come in” (National Book Foundation).

The book opens with poems that give us a glimpse into Johnson’s experiences as a young man. In “Battle Royal,” a young Johnson is stripped down, blindfolded, thrown into a ring, and told “only/ the last darky on his feet gets a meal.” In “Blues His Sweetie Gives to Me,” we feel the bitterness of the cold Chicago nights when Johnson travels there without a dime to help advance his boxing career. And advance it does, with grueling hard work and despite the relentless, ever-present racism that Johnson must endure. The book chronicles Johnson’s matches against a long line of opponents, building up to the poem “The Battle of the Century,” which refers to the famous match in which the white boxer Jim Jeffries comes out of retirement to try to take back the world heavyweight championship from Johnson. When Johnson wins, the nation erupts, both in celebrations and in violent riots.

Johnson’s famously flashy and unconventional lifestyle—in stark contrast to the racial segregation and second-class citizenship to which he is subjected— is on full display in The Big Smoke. In “Courtship,” he tells Hattie McClay, the first of three white women with whom he has a relationship over the course of the book, that they can bathe in champagne and dry themselves with hundred dollar bills. In the poem “Equality,” we see him flaunt his fast, shiny car to a white opponent he is about to meet in the ring. But while Johnson’s bravado is evident in many of the poems, we see a different side of him in the poems titled “Shadow Boxing” and “The Shadow Knows,” which are repeated throughout the book. In these, Johnson trains by sparring with his “shadow”—an inner voice that knows his deepest burdens, vulnerabilities, failures, and desires.

Outside of the ring, The Big Smoke weaves together the stories of three of Johnson’s lovers: Hattie McClay, Belle Schreiber, and Etta Duryea (whom he ultimately marries). Each speaks in her own way: Hattie through letters to Belle; Belle through FBI interview transcripts; Etta speaks to us directly. In poems like “Cooking Lessons,” “Fidelity,” and “Marriage Proposal,” we see evidence of Johnson’s physical abuse of these women; in “Aristocracy” and “Il Trovatore,” we witness the tragic toll it takes on Etta.

Matejka says he approached the writing of The Big Smoke—which refers to one of Jack Johnson’s many nicknames—differently than he might have approached writing a traditional collection. “Pretty early on I stopped thinking about the poems as stand-alone events…and started thinking about them as fragments of a character’s story” (Cloudy House). As a result, The Big Smoke is a book of poetry with a strong narrative force, one to read chronologically from beginning to end. “Even if telling the story of the first African-American heavyweight world champion is an historically important task,” noted the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Review, “The Big Smoke never labors. It reads more like a thriller.”

-

Many of the poems in The Big Smoke are written from Jack Johnson’s perspective (these are called “persona” poems). Why do you think Matejka chose to write in Johnson’s voice? What might be the risks a poet takes when attempting to speak in the voice of a historic figure, and what can be gained? If you were to write a persona poem in the voice of a figure from the past, whom would it be and why?

-

Power is a major theme throughout the book. In what ways is Johnson portrayed as both powerful and powerless? How do we see him struggle to reconcile this dynamic? In what ways do you see power abused in the book?

-

The book includes multiple poems titled “The Shadow Knows” and “Shadow Boxing” (pp. 11, 15, 32, 44, 52, 71, 92). Who or what do you think is the shadow? Can you describe the struggle taking place in these poems?

-

Describing a fight between Johnson and Tommy Burns, the poem “A Great Maltese Cat Toying with a White Mouse” (p. 24) is divided into two sections: “What I told the reporters” and “What I really meant.”In what ways did Johnson’s public statement differ from how he actually felt? What insights does this poem give you into Johnson’s other actions throughout the book?

-

Hattie McClay, Belle Schreiber, and Etta Duryea each speak in the book through a distinct form. Hattie writes letters to Belle (these poems are in the “epistolary,” or letter-writing form); Belle is questioned by the FBI and speaks through the interview form; and Etta speaks to the reader directly. Why do you think Matejka chose to use different forms for each of these women’s voices? Do the forms affect how you understand these women and their relationships with Johnson?

-

References to Johnson’s gold teeth appear in many poems, including “Letter to Belle (May 29, 1909)” (p.27), “Mouth Fighting” (p. 31), and “Gold Smile” (p. 65). What do you think Johnson’s gold teeth meant to him? What did they mean to others?

-

In “Texas Authorities Will Prosecute Champion If He Takes White Wife,” (p. 38), Johnson says “I have the right/ to choose who/ my mate will be/ without the dictation/ of any man.” What do you think it meant for someone like Johnson to have public relationships with white women? Do you think these relationships were viewed differently by black people and white people?

-

“Race Relations” (p. 43) is one of many poems that touches on the theme of what it means to be a man. Etta says: “they will all learn:/ a man is a man if he is a man.” What do you think she means? What does “manhood” mean to Johnson? How do you think it was defined by society at that time, and how is it defined today?

-

In “Equality” (p. 47), Johnson takes part in a car race with a white opponent he is about to meet in the ring. What do you think the idea of “equality” means in the context of this poem? Can you think of other poems in the collection that grapple with the idea of “equality”? How do they differ? How are they similar?

-

A number of poems take their titles from newspaper headlines about Johnson, including “A Struggle Between a Demon and a Gritty Little Dwarf” (p. 50) and “Carefree as a Plantation Darky in Watermelon Time” (p. 70). Why do you think Matejka chose to use real headlines in his telling of Johnson’s story? Do you think racial bias still appears in sports media and the press at large, or is this a thing of the past?

-

The poem “Alias” (p. 59) includes names that sports writers and others gave Johnson over the course of his career. In what ways do the names evolve over the course of the poem? Why do you think ‘Jack Johnson’ is repeated throughout the poem? Why do you think the poem ends with a question?

-

Johnson’s physical abuse of the women he loves is depicted in several poems, including “Cooking Lessons” (p. 34), “Fisticuff Difficulty” (p. 61), “Fidelity” (p. 66), and “Marriage Proposal” (p. 89). In “Fisticuff Difficulty,” Belle says, “There were times I thought he loved me enough to kill me.” What do you think she means? Do you think Johnson, as portrayed in the book, feels remorse for his behavior? Why or why not?

-

The long poem “The Battle of the Century” (p. 73) is separated into sections, with each section representing a round of the 1910 fight between Johnson and Jim Jeffries. Why do you think Matejka chose to make each round appear differently on the page (for example, by varying the line lengths and number of stanzas)? Did this affect your response to the poem and the story of the fight?

-

In “Race Relations” (p. 88), the president of the historically black Talladega College says it was better for Johnson to have “beaten Jeffries & let a few coloreds/ be murdered in the riots” than for Johnson to “lose & allow their spirits to be killed.” What do you think Johnson’s historic victory meant to the black community, and what were its costs?

-

Matejka calls Johnson “a 21st-century athlete living in Jim Crow America” (The Cloudy House). What do you think he means, and where do you see examples of this in the book? Do you agree? How do you think Johnson’s legacy has influenced—or is reflected in—athletes and sports culture today?

-

The last poem in the book is “Hubert’s Museum & Flea Circus (1937)” (p. 101). Why do you think Matejka chose to close the book with this poem? What do you make of the final question, “What would you like to know?”

-

Johnson is the subject of the play and film The Great White Hope, as well as the Ken Burns documentary Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. If you’ve seen one or more of these portrayals, how would you compare it (or them) to the story of Johnson in The Big Smoke? Do you think poetry allowed Matejka to explore Johnson’s life in ways the other forms could not? If so, how?

-

“Matejka’s Jack Johnson is a deeply flawed hero of American history,” writes the St. Louis Dispatch. Do you think Johnson was a hero? Why or why not? Is it possible to be a “flawed hero?” Can you think of other examples of “flawed heroes,” in literature or in history?