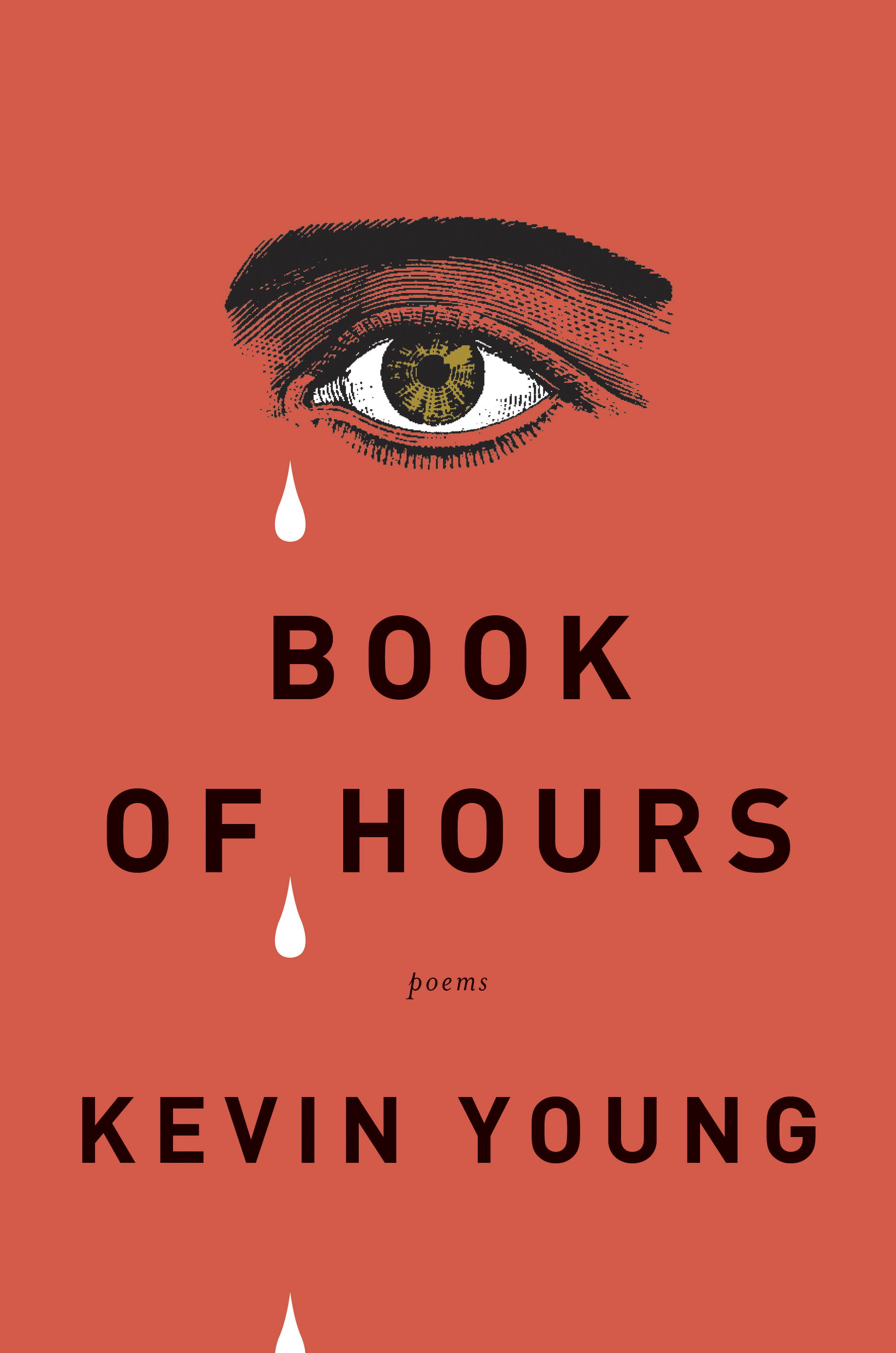

Book of Hours

Overview

Lauded today as "one of the poetry stars of his generation" (Los Angeles Times), Kevin Young is an NEA fellow and award-winning author of numerous books of poetry and prose. In Book of Hours, Kevin chronicles and links two profound life experiences: the death of his father and the birth of his son. Named one of the "ten essential poetry titles for 2014" by Library Journal, the book's themes are universally resonant, its poems at once intimate and relatable. "If you read no other book of poetry this year, this should be the one" (Atlanta Journal-Constitution). "I've read plenty of books about grief and about coming through grief in my life, but I've never before encountered a book that gets it as right as Kevin Young's Book of Hours," writes The Stranger. "It's one of those rare reading experiences that I recognized, even as I read it, as a book I was going to buy over and over again, to give as a gift to friends who've had that certain hole cut out of them, the loss that you can recognize from a distance, even in the happiest of times."

"Not the storm/but the calm/that slays me." —from Book of Hours

Overview

Lauded today as "one of the poetry stars of his generation" (Los Angeles Times), Kevin Young is a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellow and award-winning author of numerous books of poetry and prose. In Book of Hours, Kevin chronicles and links two profound life experiences: the death of his father and the birth of his son. Named one of the "ten essential poetry titles for 2014" by Library Journal, the book's themes are universally resonant, its poems at once intimate and relatable. "If you read no other book of poetry this year, this should be the one" (Atlanta Journal-Constitution). "I've read plenty of books about grief and about coming through grief in my life, but I've never before encountered a book that gets it as right as Kevin Young's Book of Hours," writes The Stranger. "It's one of those rare reading experiences that I recognized, even as I read it, as a book I was going to buy over and over again, to give as a gift to friends who've had that certain hole cut out of them, the loss that you can recognize from a distance, even in the happiest of times."

Introduction to the Book

"We don't often talk about grief and loss in our culture. Poems are a powerful way to do that" — Kevin Young in Emory Magazine

For many of us, the loss of a loved one and the birth of a child are our most profound experiences, and our most intimate. In his eighth book of poems, Book of Hours, Kevin Young poignantly chronicles the day-to-day unfolding of these events: first the grief following the sudden death of his father in 2004, and later, the sense of joy and renewal he experiences with the birth of his son. The collection was published by Knopf in 2014. "It seemed symbolic and important to me," said Young, referring to his dad, "that the book come out on the 10-year anniversary of his death" (Chicago Tribune).

Structured like a diary or a daybook—the title Book of Hours alludes to a book of daily prayer—Young says he set out to capture the "literal meaning of hours and days and moments in the process of grief and joy" (National Public Radio). In his direct, affecting poems, Young shares the most personal observations and details of his sorrow, the particular ways in which the intensity of death and birth colors how he sees the world and his everyday routines. These are feelings "you can recognize from a distance, even in the happiest of times" (The Stranger).

Poems in the first portion of the book show Young plunging into the necessary and heartbreaking tasks after his father's death: authorizing the donation of his father's organs, finding homes for his father's dogs, trying to complete what was left unfinished. Underlying the task of locating his father's dry cleaning and deciding where to donate it, as described in his poem "Charity," is the comprehension that while his father's articles can still be located, his father cannot. And as Young attempts to cope, he also struggles with jarring daily reminders of his loss, as when he receives a call from a telemarketer who leaves a message acting as though she has spoken with Young's father just that day. People experience grief differently, he indicates in his introduction to the anthology The Art of Losing (Bloomsbury, 2010); poetry can bridge the gap between us and bring us together.

As the book continues, it shifts into poems about the entry of Young's son into the world, signaling a kind of rebirth for Young, with titles such as "Starting to Show," "First Kick," "Breaking Water," "Teething," and "Blessings." His poem titled "Crowning" was in part a reference to the prevalence of crowns in the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, how Basquiat crowns "those he loves" (Failbetter.com). In "Expecting," Young describes hearing his son's heartbeat for the first time.

Named one of ten essential poetry titles for 2014 by Library Journal, Book of Hours won the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets as well as the Donald Justice Award, and was a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Award. "Sometimes, if you're looking straight at something, you can't see it as well," said Young. "It's like looking at an eclipse. You've got to have that mirror to see it right" (Guernica). His poems are "almost all composed of very short lines choked with dashes and ampersands, like someone gasping for breath between bone-deep wails. But together, they form a narrative, a memoir of what it's like to come through to the other side" (The Stranger).

How to Read and Talk About Poetry (Art Works Blog, 12/2/2016)

- The poem “Grief” is just two lines: “In the night I brush / my teeth with a razor”. Where do these two short lines lead you? Does the poem's length affect how you react? Later, Young includes another short poem, also called “Grief”. Do you read the second poem as a continuation of the first? How do these poems make room for what can't be said? How does the speaker's grief clash with the external world's—friends, family, neighbors—responses and reactions to that grief?

- One of Young's modes of wordplay is the double entendre, or double meaning. The title “Effects”, for instance, implies results or consequences on the one hand, and personal belongings on the other. “Asylum” similarly fluctuates between implications of sanctuary and illness. What other double meanings are at work in Book of Hours? What purposes do these double meanings serve?

- The first section of Book of Hours is titled “Domesday Book.” The Domesday Book is an actual volume from the 11th century detailing an extensive property survey of England and Wales for taxation purposes. “Domesday” (early English for “Doomsday”) is also the Christian Day of Judgment. How are these two concepts of reckoning—one, mundane accounting, the other, eternal judgment—reflected in this section of Young's book? Why do you think he chose that name?

- In “Wintering”, Young addresses the difference between mourning and grief: “Mourning, I've learned, is just / a moment, many // grief the long betrothal / beyond.” Do your own experiences of mourning and grief align with Young's?

- At the end of “Easter,” describing his final encounter with his father, Young writes: “For once that Easter // I told him”. What did Young say to his father? How do you know? Why doesn't Young tell the reader directly?

- The poem “Miscarriage” asks “How to mourn what's just // a growing want?”. What connections do you see between the way Young mourns his father and the way he mourns the miscarriage? Why is there a blank page after this poem?

- Young's poems rely on familiar rhythms of change, such as the cycles of days and seasons, and the ordinary and ubiquitous changes of aging. How does sudden, unexpected change interact with these quieter forms of change? Can they be separated? Is Book of Hours more about one kind of change than the other?

- As Young interacts with his yet-to-be-born child, successive poems introduce new kinds of information. “Expecting” is an encounter through sound (“You are like hearing / hip-hop for the first time”); “Ultrasound” is a visual encounter (“shadow // boxer, you raise a hand /to shield your face”); and “First Kick” adds the sense of touch. How does Young's relationship with his son evolve through these three poems, with the addition of each new sensory dimension?

- In “Nesting”, Young says about the human heart: “Without warning, / the story it tells // to no one ends— / or begins, a shadow // grown beneath the breast.” Why does the heart tell its story “to no one”? How and why does Book of Hours juxtapose birth and death? What effect do these bookends to the human experience have on how you, yourself, live your life?

- Reacting to the “machines that trace our breathing in hospitals,” Young states that they “lie— // the heart is no line // crossing the palm, / no jagged green— // just this twin fist opening”. How do the devices and metrics we rely on in modern medicine shape our perception of what the body is, and how human life operates? Have you ever seen yourself differently after an illness, injury, or medical visit?

- In “Labor Day”, the anticipation of Young's son's overdue birth overlaps with the baseball game Young is watching, and the two—baseball and birth—seem to merge. Have you ever been so preoccupied with something that you began to see echoes of it in unlikely places? How has anticipation altered an experience you've had, in positive or negative ways?

- Reflecting on the recent birth of his son, Young writes: “I believe pregnancy is meant / to teach us patience, / then impatience”. How does Young portray his wife's experience of pregnancy? How much of that experience can they share, and how much of that experience is inaccessible to Young himself? Do you think his wife would draw the same conclusions about the meaning of pregnancy?

- Young's poems often address his son directly as “you” or “son”; do you think this urge to talk directly to his son is related to what Young describes as “my dead father's silence”? How is Young's approach to fatherhood shaped by the passing of his own father? How do families carry memories across generations that might never meet one another?

- Throughout Book of Hours, physical extremes of birth and death happen to other people, not to Young. Does Young keep his own body confined to the background in the book, or does it also have an important role to play? How does a first-person account of illness, as in “Ruth”, change or deepen Young's position as the “narrator” of the book?

- What are other ways in which Young examines the body in this book? How are the sick body, the dead body, the living body, the unborn body, the newborn body, the inhuman/animal/inanimate body—compared, contrasted, and conflated throughout? How does your understanding of your own body change with the experiences—losses, gains, emotional ups and downs—you have in life?

- Young's book takes its title from a Christian devotional prayer book. In what ways might these poems be prayers?

- Do you agree with Young's assessment that life is “the long disease”? Are there other moments or poems in Book of Hours that contradict that attitude? How do you interpret the final line of the book, “Why not sing”?

- Throughout Book of Hours, Young returns to his father's death, each time giving the reader new details or revisiting parts that had been left out. In contrast, Young tells the story of his son's birth in sequence, describing how he comes to term, is born, and begins to grow up. Why does Young use a circular narrative to tell his father's story and a linear narrative to tell his son's? Could Book of Hours have been written in the opposite way?

- Does Book of Hours tell a single, unified story? Are there individual poems that wouldn't make sense outside the context of the book? Could Book of Hours have been written as a novel or prose autobiography?

The Book of Hours discussion questions #1, #15, and #16 were adapted from materials on the Academy of American Poets website.